"No one can solve this problem alone, but together we can change things for the better."

The ATT at 10: The View From Mexico

May 2023

By Alejandro Alba Fernández

Ten years ago, the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) was adopted by the UN General Assembly with the promise to establish common standards for the international trade in conventional arms in order to reduce the terrible human consequences caused by the illegal, irresponsible transfers of these weapons.

Tragically, in the years since the treaty came into force, the illicit arms market has not been contained. On the contrary, diverse research indicates that the trade has grown as unauthorized actors across the globe continue to profit from weapons at great human cost. The diversion and illicit trafficking of arms remains a serious problem that affects international peace and security, destabilizes countries and regions, cripples development, and causes excessive violence and unacceptable human suffering.

On this anniversary, it is worth asking whether the ATT has fulfilled its objectives. Although significant progress has been achieved in the institutional consolidation of the treaty, there is still a long way to go to assess its overall success. As recent years have demonstrated, there is a worrying inertia in terms of new states acceding to the treaty and states-parties meeting their reporting and transparency commitments. To fulfill the treaty’s promise and meet the pressing challenges of a world awash in conventional arms, states-parties and other supporters must place greater emphasis on improving practices and transparency in the arms trade, including strengthening schemes for preventing diversion, improving export risk assessments, and ensuring mechanisms for the verification of authorized uses and end users.

National Control Systems

One method of measuring overall ATT compliance is the establishment of national control systems. Article 5 of the treaty obliges states-parties to maintain such systems, which must include a national arms control list and clearly identified, competent national authorities and designated focal points to facilitate and expedite the exchange of information on matters related to implementation.

Although most ATT members have reported having national control systems, little is known about how they work, whether they are effective, and whether they are regularly updated. For example, the updates of national authorities involved in implementing the treaty and the national contact points are useful for addressing practical aspects of cooperation and information exchanges. Even so, more attention on this matter is needed.

National control systems must be effective and applicable to all arms imports and exports in such a way that they prevent the authorization of treaty-prohibited transfers.1 To ensure this objective, exporting countries, before authorizing a transfer, must establish risk assessments that allow them to evaluate in an objective, nondiscriminatory manner the potential of that weapon to undermine peace and security or to be used to commit crimes of international concern. Exporting countries, in collaboration with the importing state, also must take measures to mitigate any risk of this nature.2

Risk Assessments

State-parties must carry out risk assessments before authorizing a treaty-covered arms transfer and perhaps afterward if new, relevant information comes to light. In some cases, legal arms transfers have ended up in the wrong hands in conflicts in Afghanistan, Myanmar, Yemen, and other countries and are an indicator that exporting countries need to do more to improve their risk assessments.

Although this evaluation is one-sided—carried out by the exporting state—it cannot be a mechanical exercise, and the role of the importing state should be better defined. The assessment must be exhaustive, objective, and on a case-by-case basis. It must include information provided by the importing state and analyze all relevant factors, including compliance with international law and international humanitarian law by the importing state, diplomatic reports on the security and political situation in the importing country, and an evaluation of the potential that the weapons may be used to carry out illegal acts or to facilitate serious acts of violence. In this regard, risk assessments should give greater consideration and weight to the provisions of Article 7.4, which establishes criteria to avoid transfers that facilitate gender-based violence.3 This is extremely relevant because, in armed conflict, women and girls are disproportionally affected by arms violence.

Carried out seriously and under the parameters required by the ATT, risk assessments could lead to the denial of an arms transfer. The treaty refers to information that is provided by the importer, but nothing prevents a third state from providing additional information that helps to properly inform risk assessments. This is especially important when dealing with data that document detected or suspected diversion that has affected the state providing the information.

Preventing Arms Diversion

ATT states-parties involved in arms transfers are obliged to prevent their diversion.4 Although this is a fundamental obligation, it is not uncommon that weapons that were legally transferred to one country later appear in another, fueling conflict and violence.

The Conference of the States Parties is the vehicle for promoting information exchanges and practices to prevent, mitigate, address, and eradicate arms diversion among ATT members. Dialogue among the parties characterized by good faith, respect, and collaboration is the basis for achieving the ATT objectives.

It is a cause of concern, however, that despite the fact that there is an online platform for the exchange of information among ATT member states and states that have signed but not ratified the treaty, it largely has been disregarded. Some members argue that before using the platform, it is necessary to determine the type of information that can be shared. Others stress that technical and confidentiality criteria, which so far have not been addressed, must be considered first. The result is that this mechanism has not been effective for the exchange of information that is necessary to analyze and combat cases of illegal arms transfers.

The Diversion Information Exchange Forum, active since 2022, is the most recent promise within the ATT framework to prevent and combat arms diversion. The forum is the first mechanism of its kind that seeks the exchange of technical and operational information to identify and combat suspected or detected cases of diversion and illegal arms trafficking.

To strengthen trust among members, only the participation of states-parties and signatories is contemplated for now due to the sensitivity and confidential nature of the information that is meant to be shared in the forum. Civil society has questioned this format, and in the near future, the forum should consider including other stakeholders that have very relevant research and information that could contribute to analyzing cases. Given the creativity of arms traffickers, it is necessary for the conference to monitor constantly the effectiveness of its mechanisms and encourage the parties to adapt their national regulations and laws as necessary to prevent, combat, and reduce the risks of diversion; tighten risk assessments; and improve mitigation measures in the process of authorizing arms transfers.

Strengthening Reporting

States-parties are obligated under Article 13 to submit initial and annual reports on arms exports and imports. In recent years, however, compliance has weakened: Fewer annual reports have been submitted, fewer have been submitted on time, several countries have not submitted their annual and initial reports at all, more states have made their reports nonpublic, and more states are excluding information considered sensitive for security and commercial reasons and are reporting aggregate data that make independent analysis difficult.5

These are alarming trends given that a fundamental treaty obligation is not being fulfilled adequately. This has consequences for the analysis of flows of arms transfers globally and regionally, the building of trust among treaty states-parties, international cooperation, and the effective implementation of the treaty. In terms of the risk assessments exercise, the information contained in these reports can help to support decisions to grant or revoke arms transfer licenses and even facilitate the identification of possible cases of arms diversion. In addition, weak reporting related to the ATT undermines its overall compliance vis-à-vis other arms control instruments.

It is too early to draw definitive conclusions about these trends. The global pandemic may have affected the ability of states to submit reports. Developing countries in particular still face difficulties in submitting treaty-required reports. In some cases, only a single official is filing reports to comply with a number of other international and regional arms control regimes besides the ATT, or officials charged with reporting responsibilities lack capabilities. There are also challenges to collecting information from diverse governmental agencies and, in some instances, a lack of political commitment to their obligation to submit reports.

It is too early to draw definitive conclusions about these trends. The global pandemic may have affected the ability of states to submit reports. Developing countries in particular still face difficulties in submitting treaty-required reports. In some cases, only a single official is filing reports to comply with a number of other international and regional arms control regimes besides the ATT, or officials charged with reporting responsibilities lack capabilities. There are also challenges to collecting information from diverse governmental agencies and, in some instances, a lack of political commitment to their obligation to submit reports.

More attention should be devoted to the subject of reporting and to the development of measures that can address legitimate concerns and solve structural problems. The treaty’s working group on transparency and reporting is developing initiatives and tools to encourage reporting and to improve the quality of reporting by including more useful and relevant information in them. Some tools developed by the working group are an outreach strategy led by the conference president that would engage states-parties and drive home the importance of meeting their ATT reporting obligation, a voluntary peer-to-peer project to help states-parties with the preparation of reports, a guidance document on the annual reporting obligation, and an online reporting tool posted on the ATT website.

The working group recently updated the reference templates for the initial and annual reports. These updates are timely and pertinent because they seek to resolve inconsistencies, errors, doubts, and omissions in the submitted reports. Although use of these templates is voluntary, because the treaty establishes the obligation to report without specifying the manner of reporting, they are widely used and facilitate the work of members. The working group also promotes the use of the information exchange platform located on the ATT website and the possible development of an online database that could facilitate the search and cross-checking of information contained in the reports that are submitted in compliance with the treaty.

It is essential to continue efforts to support and encourage timely, meaningful reporting and to support states-parties that face difficulties in meeting their obligations. The ATT Voluntary Trust Fund is a valuable resource that can support projects aimed at developing and improving reporting capacities. States-parties not in compliance with the reporting requirements should consider using the fund.

Also, the Diversion Information Exchange Forum can facilitate the exchange of practical and operational information that helps to deal with detected or suspected diversion cases. For regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean, where there are no formal channels for exchanging information among national governments to prevent diversion and the regional mechanisms focused on illicit arms trafficking have had few results, the forum represents an opportunity to exchange information among the countries at the regional and subregional levels.

Toward Greater Participation

As the number of conflicts around the world continues to increase, many major arms exporting and importing countries are not yet parties to the treaty. Notable absences include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, India, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the United States.

Some of the countries that have joined the treaty in recent years are Afghanistan, Andorra, Canada, China, Lebanon, the Philippines, and São Tomé and Príncipe, which is encouraging given the geographic diversity and the countries’ profile in the arms trade. Currently, the treaty has 113 states-parties; 28 states that have signed the treaty but have not ratified it; and 54 states that remain outside the regime.6

Only eight years after the treaty entered into force, a significantly high number of countries have ratified it as states-parties, and that is definitely a positive accomplishment. For the ATT to achieve its objectives, however, the participation of all states is required.

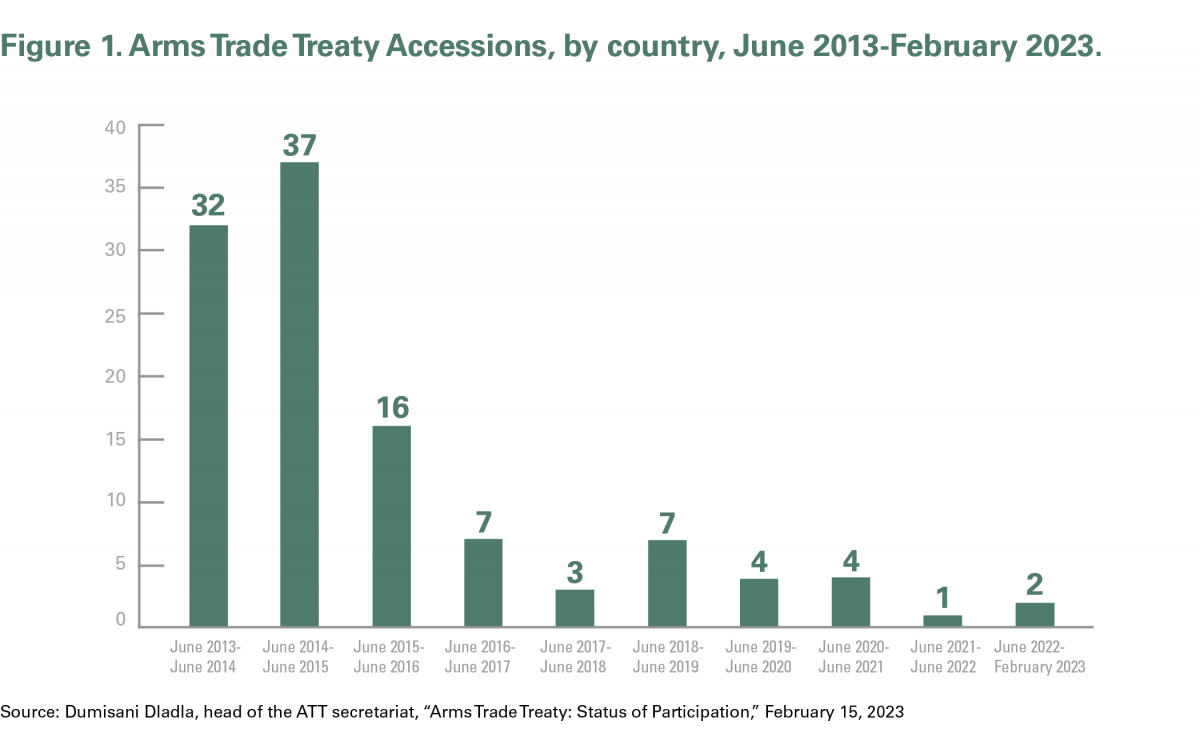

Moreover, in recent years, the trend of new treaty accessions has decreased (fig. 1). Although there were more than 30 annual ratifications in the early years, in the last two years the growth was very modest, with one country in 2021 and two in 2022.7

This should not be interpreted as a lack of support for the treaty. It is logical that, in the early years, a large number of countries would join the new regime. Yet, this trend means that achieving new ratifications and accessions in the future will require more focused actions, a medium- or long-term perspective, and sustained efforts to address the reasons and challenges that have prevented more accessions.

For example, some countries do not consider the treaty a priority instrument or do not see the potential benefits of joining it. Others believe that membership would imply disproportionate burdens because they must fulfill other reports for several other arms control regimes. Some countries believe that before joining the treaty, they must establish or develop their national arms control systems and the legal framework that ensures their implementation. Other states simply believe that the treaty does not respond to their strategic interests.

It is striking that the Asia-Pacific and African regions, the two that suffer the most from the armed violence associated with diversion and illicit arms trafficking, historically report the lowest numbers of ATT states-parties.8 Achieving universal treaty membership requires particular attention to these regions.

States-parties should increase efforts at expanding treaty membership. Germany and South Korea, the current chairs of the working group on universalization, have proposed a constructive approach to develop medium- and long-term plans, focus outreach efforts and resources on underrepresented regions, and enlist treaty-supportive states to advocate for more accessions and ratifications in their regions. Special attention also should be given to engaging major exporters and importers, which set the trends in the global market, as well as to using the support of regional and subregional organizations.

Over the years, several international actors and civil society organizations have played a crucial role in favor of universalization through awareness campaigns and providing legal and technical assistance to countries that are considering joining the ATT. These efforts should receive more visibility and support by states-parties in political and financial terms. Above all, the best way to get more accessions is to demonstrate that the treaty works.

|

The Mexico Example Mexico faces a great problem with the illegal entry of roughly half a million weapons annually through its northern border. Most of the weapons end up in the hands of criminal groups, inflicting untold suffering on the population. Combating diversion and illicit arms trafficking is a priority that Mexican foreign policy addresses in various international forums, most notably the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). The treaty has helped Mexico to visualize and raise awareness about challenges and consequences of diversion and illicit trafficking of conventional weapons, promote standards for responsible international arms trade, and take advantage of its provisions on international cooperation to exchange information and consult on best practices in an effort to prevent and combat these illicit trafficking cases. In this regard, Mexico's general evaluation of the treaty is positive, although it recognizes the challenges the treaty faces and is therefore involved actively and purposefully Mexico played an active role in the adoption of the treaty, its entry into force, and the efforts in favor of universalization and effective implementation. The first conference of states-parties, chaired by Mexico in 2015, established the general basis of the bodies that monitor Mexico’s role in the ATT is reflected in the activism of its delegations; in the continuous work that it carries out along with other actors, including governments and civil society organizations, to promote its effectiveness; and in its participation in the treaty governing bodies. It has held relevant positions within the institutional structure of the treaty, such as the regional vice presidency of the Eighth Conference of States Parties, chair of the forum on the exchange of information on diversion, the co-chair of the working group on transparency and reporting, and member of the ATT Voluntary Trust Fund selection committee. As co-chair of the working group, Mexico promoted the creation of the forum, believing that this will help to create the necessary conditions for open and direct exchanges among the members. It is essential to ensure that this mechanism is effective. Mexico has also underlined the responsibility that states have to ensure that the weapons that transit through their territories are not used to commit serious crimes and that the states are not in violation of their obligations under international law. It has promoted the treaty’s synergies and complementarities with other international and regional arms control regimes, such as the UN Program of Action to Prevent, Combat and Eradicate the Illicit Traffic in Small Arms and Light Weapons, the Protocol on the Control of Firearms, the Wassenaar Arrangement, and the Inter-American Convention Against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Ammunition, Explosives. Although Mexico has a strict national arms control system and systematically submits its reports to the ATT, more can be done to ensure full compliance with its obligations in the domestic domain. These steps would include more transparency in the way the country implements the ATT and manages the licensing process. It would be useful to know how the country carries out its risk assessments, what factors are taken into account, and whether it has experienced challenges in preparing its reports and improving the quality of information they contain. Mexico should encourage more of its technical, licensing, and enforcement officers to participate in the Conference of States Parties and its preparatory meetings, so that they can share experiences in the detection of illicit transfers and diversion of arms that end up in the hands of criminal groups. Mexico must continue contributing to the efforts to ensure the effective implementation of the ATT because it is a case study in all the elements needed to achieve a more responsible international arms trade. That is not an easy task, given the obscure interests pursued by the different actors involved in diversion and illicit arms trafficking, but it is a moral and ethical imperative for the innocent victims who suffer every day from the impacts of armed violence.—ALEJANDRO ALBA FERNÁNDEZ |

ENDNOTES

1. Pursuant to Article 6 of the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), arms transfers that violate UN Security Council resolutions or other international obligations or that take place with the knowledge that the weapons could be used to commit genocide, crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, or other war crimes typified in international agreements are prohibited. Arms Trade Treaty, April 2, 2013, 3013 U.N.T.S. 269, art. 6.

5. For trends in ATT reporting, see Arms Trade Treaty Baseline Assessment Project, “Taking Stock of ATT Reporting,” Stimson Center, August 2022, https://www.stimson.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Report_Taking-Stock-Web.pdf.

6. Arms Trade Treaty, “Treaty Status,” n.d., https://thearmstradetreaty.org/treaty-status.html?templateId=209883 (accessed April 25, 2013).

7. Dumisani Dladla, “Arms Trade Treaty: Status of Participation,” February 15, 2013, https://thearmstradetreaty.org/hyper-images/file/ATT%20Secretariat%20-%20Status%20of%20Participation%20(15.02.2023)/ATT%20Secretariat%20-%20Status%20of%20Participation%20(15.02.2023).pdf.

8. As of May 31, 2020, the regions with the lowest number of ATT members were Africa (27 of 54 countries), Asia (eight of 14), and Oceania (five of 14). Europe (39 of 43 countries) and the Americas (26 of 35) have a higher regional proportionality of states-parties. See “State of the Arms Trade Treaty: A Year in Review June 2019–May 2020,” ATT Monitor 2020, n.d., https://attmonitor.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/EN_ATT_2020_State-of-the-ATT.pdf.

Alejandro Alba Fernández, a member of the Mexican Foreign Service, served as chair of the Arms Trade Treaty Diversion Information Exchange Forum in 2022 and co-chair of the treaty’s Working Group on Transparency and Reporting from 2019 to 2021. The author's opinions are his own and may not reflect the positions of the government of Mexico.