Learning on the Fly: Drones in the Russian-Ukrainian War

January/February 2023

By Kerry Chávez

The international community has watched with bated breath as Ukrainians resisted, even routed Russian forces on many fronts since the latter’s invasion in February 2022. Based on its size, reputation, and bravado, many, including the Kremlin, expected the Russian military to trounce its target in short order.

Instead, its stunted progress has induced plenty of double-takes and debates, suggesting flaws in Russian intelligence, motivation, morale, and logistics. There is likely some truth in each of those explanations, but one factor stands out for its differential use and power to explain the Ukrainian upset: drones.1 The Ukrainians have held the line because they harnessed a crucial human and technological resource at their disposal, commercial drones, which have been decisive in the unexpected outcome so far. The Russians faltered because they overlooked them, but they are resurging because they learned from it. These lessons have implications for current and future wars, for preponderant militaries such as the United States all the way to underresourced rebels.

Instead, its stunted progress has induced plenty of double-takes and debates, suggesting flaws in Russian intelligence, motivation, morale, and logistics. There is likely some truth in each of those explanations, but one factor stands out for its differential use and power to explain the Ukrainian upset: drones.1 The Ukrainians have held the line because they harnessed a crucial human and technological resource at their disposal, commercial drones, which have been decisive in the unexpected outcome so far. The Russians faltered because they overlooked them, but they are resurging because they learned from it. These lessons have implications for current and future wars, for preponderant militaries such as the United States all the way to underresourced rebels.

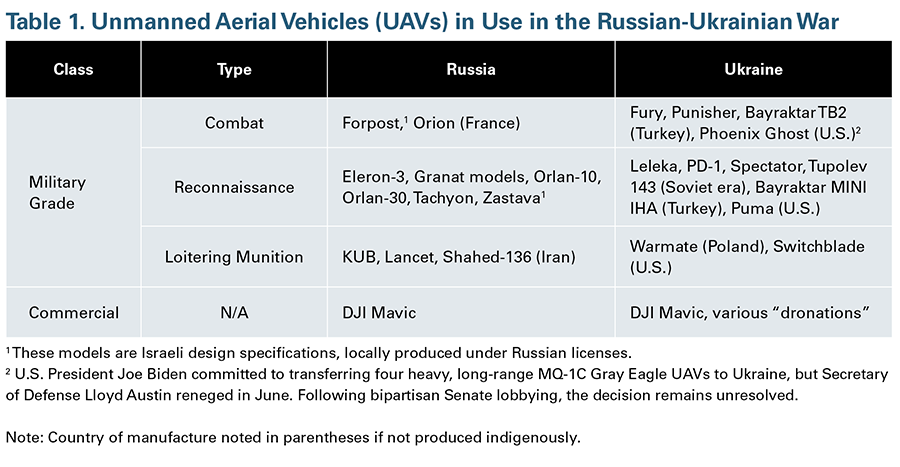

The Ukrainian and Russian sides both have admirable drone, or unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), arsenals comprising combat and reconnaissance military-grade models and commercial versions. Military-grade platforms have greater range, altitude, payload, endurance, precision, and data link security. These optimized, more rugged features come at high financial, technical, and infrastructural costs. Consequently, as with all exquisite airpower, they are relatively scarce and difficult to replace. For instance, Russia reportedly possessed only 20 Orion combat drones at the start of 2021. Loath to lose them, users usually field these platforms cautiously and precisely, leaving their limits unreached and their flexible potential untapped. Conversely, commercial drones are far more affordable, available, and user friendly. These models are considered expendable, and users often field them daringly in all sorts of ways. Overall, each type of drone has its trade-offs.

Russia has a larger indigenous drone capacity, producing advanced platforms in all categories, and Ukraine has larger external support (table 1). This is meaningful considering how international sanctions applied to Russia have reduced the ability to replenish a waning fleet either with complete substitutes or component parts. Russia’s recent deal to procure Iranian loitering munitions is a stark case in point. Iran is a disreputable drone supplier to many terrorist groups, and the regime is under enough domestic pressure over human rights abuses that its ability to deliver on this deal might become tenuous. Thus, not only must Russia look abroad to supplement its depleted drone arsenal, but the choice to rely on Iran suggests that it has few other options. That aside, Russia and Ukraine have a comparable assortment of military UAVs across application types.

Russia’s drone fleet was almost entirely indigenous and exquisite at the start of the war, and it was not unt820il midsummer that the military pivoted toward commercial drones and approached Iran to supplement its diminishing military stock. Meanwhile, a mere day into the war, the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense issued a social media call for citizens to donate hobbyist drones in droves.2 By the time Russia was beginning to incorporate simpler drones in July, the Ukrainian effort had coalesced into a global fundraising initiative to build an “army of drones,” including thousands of commercial models.3

Russia’s drone fleet was almost entirely indigenous and exquisite at the start of the war, and it was not unt820il midsummer that the military pivoted toward commercial drones and approached Iran to supplement its diminishing military stock. Meanwhile, a mere day into the war, the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense issued a social media call for citizens to donate hobbyist drones in droves.2 By the time Russia was beginning to incorporate simpler drones in July, the Ukrainian effort had coalesced into a global fundraising initiative to build an “army of drones,” including thousands of commercial models.3

More fundamentally, an inventory of each side’s drone models does not account for how these actors are wielding them, sometimes as standalone assets and other times in combined arms configurations. Too often, analyses of emerging technologies overfocus on the technologies. Impassive tools, they cannot be dissociated from the human dimension and the strategic context from which they emerge. It is doctrine that drives military action and doctrine that has made the vital difference in the war.

Doctrinal Differences

Military doctrine refers to the framework guiding how an armed force integrates, operates, and adapts to achieve objectives. It is both durable, reflecting a force’s experience-borne perspective about what works, and dynamic, outlining the intellectual tools to solve problems with new ideas, technology, and organization. Rather than what to think, doctrine informs how to think in battlespaces amid the fog and friction of war.4

Tactics, techniques, and procedures are central expressions of doctrine that determine how militaries structure and employ troops and equipment in their missions. Prior to the invasion of Ukraine, Russia expanded its arsenal of reconnaissance drones, touting it as game-changing technology and telegraphing a concept of operations based on advance airborne intelligence. This relied to some degree on doctrine and skills learned in Syria, conclusions about Azerbaijani successes in Nagorno-Karabakh, and clashes in the Donbas since 2014.5 It seemed surprising then how slowly Russian forces progressed, how often they walked into ambushes, and how minimal their drone use appeared to be once the invasion began.

By the logic of traditional aerial doctrine, it should not have been so surprising. Military airpower is advanced and expensive. Building, fielding, maintaining, and replacing assets are major undertakings. Losing a platform is a significant setback. Beginning from a baseline of this scarcity logic, Russia seemed to cautiously field its military-grade UAVs for high-stakes maneuvers and high-value targets. This contributed to subpar intelligence, disjointed logistics, and fractured efforts to advance on the battlefield. As Ukraine’s aerial defenses eliminated several Russian reconnaissance drones early in the war, this logic intensified amid questions about the depth of Russia’s drone fleet and the longevity of its vital aerial campaign.

Meanwhile, Ukraine densely integrated the full spectrum of UAVs into its force structures for reconnaissance and strikes from the start. Amassing what they called a “mosquito air force” of commercial drones, especially the four-rotor helicopter models (quadcopters) with vertical takeoff and landing and hovering abilities, Ukrainian fighters were able to maintain a bird’s-eye view of the war.6 Given that they are relatively cheap and accessible, fighters were untroubled to send them out on demand.

Commercial drones are expendable, equivalent in cost to a small supply of ammunition. As with fired ammunition, loss is built into a small drone’s mission such that military forces do not feel compelled to withhold them on the front lines. Despite initial skepticism about the ragtag Ukrainian drone fleet from Mavics to military-grade models, analysts quickly determined that “it’s wreaking havoc on the Russian army.”7

Ukraine’s prolific use of drones has dramatically affected battlefield behavior. Fighters can observe troop positions and movements, improve targeting for conventional weapons, harass and pressure enemy forces, and video successes that can later be publicized to rally support and demoralize the Russian side. Ukraine’s ability to blend commercial drones into its broader aerial arsenal and team it with traditional weapons and ground troops is a bedrock of its success at resisting the more powerful Russian military.

One Russian defense analyst admitted that “Ukrainians learned how to use their old Soviet guns together with commercial quadcopters. As a result, they have better situational awareness, and better target designation.… To put it bluntly, we do not have air supremacy.”8 Six months into the war, Russian General Yury Baluyevsky affirmed that commercial UAVs have revolutionized reconnaissance and artillery weapons fire, including target acquisition and adjustment, and become a true symbol of modern warfare.

Why did Ukraine innovate so well with UAVs? Why did Moscow fail at this, especially because Russian officials previously had seen this strategy in Syria and the Donbas and acknowledged it to be important? An anonymous U.S. volunteer fighter embedded with a Ukrainian unit pinpointed the reason in November.9 He explained that drones are democratized throughout the Ukrainian rank and file, with command and control decentralized into “islands of forces” that have the freedom to alter tactics on the fly. This enables units to be effective and mobile in a battlefield that is fragmented and fast-moving. The fighter concludes that, “The reality is we are droning them to death.… This is a doctrinal issue.… [T]hey seemingly decided rather early on that this type of [island] structure would work very efficiently against the somewhat lumbering doctrine of the Russians.”

This Ukrainian doctrine arose from necessity. Weaker combatants innovate or die. Those who survive cleverly leverage what resources they have. They pull from available experience, including nonmilitary experience, and experiment more readily. They accept trade-offs that traditional militaries might not, such as rifts in the command chain and information flow or risks accompanying unsecured datalinks.

The traditional, lumbering doctrine of the Russian military has struggled against and struggled to incorporate these scrappy methods. A Russian media report highlighted that this mass use of commercial drones by Ukrainian fighters is “a kind of revolution from below, a very rare case for conservative military circles. Drones entered the army from civilian life.… This is how this practice has spread since 2014.”10 Indeed, Ukrainian militias turned to commercial UAVs after Russia seized Crimea in 2014 and separatist clashes ratcheted up in the Donbas, calling it drone warfare for the poor.

Russia’s and Ukraine’s differential doctrines reflect their military cultures (traditional vs. entrepreneurial), risk profiles (averse vs. acceptant), civil societies (siloed from state affairs vs. highly porous) and fighting animus (hubris vs. gumption). The director of a Russian nongovernmental organization that is now providing small UAVs to the country’s platoons on the battlefield discussed this in November.11 He observed that commercial drones have featured in past conflicts, including the Donbas, but not to this scale and effect. Thus, “proudly open[ing] the 1980s ground force combat manual and [determining that] everything is fine with us,” Russia maintained focus on traditional airpower. The director noted that the United States has done the same, that “none of the modern armies of the world was ready for the Mavic phenomenon.” Seeing the impact of small drones on targeting, information processing, and control, he advocated a shift in military science and worldview from ground troops to generals to government. Russia is beginning to internalize that shift.

Adaptation

Four months into the war in Ukraine, the Russian military launched a second major offensive. This one was different. A more competent force emerged. Most glaringly, ground units began to incorporate commercial drones into their tactics, techniques, and procedures. After watching them used against them to profound effect, Russia emulated Ukraine’s mix of military and commercial UAV use. Although Russian officials had endorsed drones as a key force enabler and even discussed the integration of quadcopters before the war, it apparently took the war itself for Russian doctrine to accord with rhetoric.12

Fascinatingly, this shift was driven by Russian field commanders rather than generals. Following a late June meeting with soldiers from the front line, a government official warned that “we are there like blind kittens—we need quadcopters.”13 In a candid series on Telegram entitled “Cry for Copters,” a Russian artilleryman stressed that all ground units from platoons upward need and have needed from day one to be saturated with commercial drones for reconnaissance and strike. He condemned the “amazing attitude” of military leadership who ignored the widespread plea from foot soldiers who use their own funds to buy quadcopters, spare parts, tools, and firmware.14

Fascinatingly, this shift was driven by Russian field commanders rather than generals. Following a late June meeting with soldiers from the front line, a government official warned that “we are there like blind kittens—we need quadcopters.”13 In a candid series on Telegram entitled “Cry for Copters,” a Russian artilleryman stressed that all ground units from platoons upward need and have needed from day one to be saturated with commercial drones for reconnaissance and strike. He condemned the “amazing attitude” of military leadership who ignored the widespread plea from foot soldiers who use their own funds to buy quadcopters, spare parts, tools, and firmware.14

As with Ukrainian fighters who have been adept with commercial drones in the Donbas since 2014, Russian fighters there have been on the forefront of support for this shift. In May 2022, Russian-based separatists who control Donetsk established a training facility for commercial drone pilots in combat. One of its founders noted that civilian UAVs turn conventional weapons into sniper rifles, especially for moving targets.15 This tactic, penetrating aerial defenses with small drones and hovering undetected over targets to calibrate targeting and time follow up strikes, has become a staple in the war.

As Russia’s adaptation with commercial drones deepened, official and state media accounts increasingly have amplified its importance. In October, the Russian newspaper Izvestia announced “immediate plans” to outfit platoons with multiple quadcopters to be used in tandem for surveillance, searches, and strikes.16 A month later, it underlined that, “at this point, nothing gets done without quadcopters.… There are no reconnaissance devices comparable to them in capabilities.”17

Two other developments indicate how vital small UAVs have been in this conflict. First, coinciding with its own adaptation with hobbyist drones, the Russian military made targeting Ukrainian UAV operators a top priority. Given that commercial datalinks are unsecured, it is easier to detect pilots’ positions, leading operators on both sides to develop steel nerves and tactics to move continuously on foot during flight and to deploy drones in short forays to avoid detection. As drone use has become increasingly dense, diverse, and dangerous, both sides continuously watch, probe, and adapt to circumvent one another’s aerial strategy and defense. They are truly learning on the fly.

Second, in October the Russian company Almaz-Antey began large-scale production of an indigenous quadcopter, the type of commercial drone making the most difference, to sidestep the politics and expense of importing. At the government’s request, it could be easily convertible to combat use.18 This marks a major evolution: from an era of solely military UAVs to the emergence of a vast commercial drone market to militaries mass-producing commercial models for state arsenals. These trends, spanning military affairs from doctrine to combat tactics and stretching back and forward into civil society, suggest that small drones will be organic to modern conflict.

Implications

The exploitation of small UAVs in conflict or in support of a violent agenda is not new. Aum Shinrikyo experimented with quadcopters to disperse sarin in Tokyo as far back as 1995. Since the commercial drone industry began mass production around 2012, several groups have incorporated them into their inventories for reconnaissance, propaganda generation, and weaponization. The Islamic State group at its peak stands out as an ace innovator, but drones have featured in the Syrian civil war and Myanmar insurgencies, are a fixture in the cartel and smuggling underworlds, and were a fundamental asset in the Donbas well before the full war was unleashed.19

The role of UAVs in the war, however, is distinct. First, the scale of their use in this conflict is dominant. Second, past applications of drones certainly have helped weak actors contend against stronger adversaries in unconventional conflicts, but now there is a precedent for their utility in a total war against a major power. Third, although small UAVs have been in many a rebel’s backpack and a terrorist’s tool kit, the effort to tuck them into as many Russian and Ukrainian rucks as possible is a significant pivot in state military behavior. Finally, the salience of this war has attracted more attention than other theaters where hobbyist drones have been employed. Overall, the UAV phenomenon in this war has implications across time, space, and domains.

The role of UAVs in the war, however, is distinct. First, the scale of their use in this conflict is dominant. Second, past applications of drones certainly have helped weak actors contend against stronger adversaries in unconventional conflicts, but now there is a precedent for their utility in a total war against a major power. Third, although small UAVs have been in many a rebel’s backpack and a terrorist’s tool kit, the effort to tuck them into as many Russian and Ukrainian rucks as possible is a significant pivot in state military behavior. Finally, the salience of this war has attracted more attention than other theaters where hobbyist drones have been employed. Overall, the UAV phenomenon in this war has implications across time, space, and domains.

Regarding time, the phenomenon will shape the current conflict and echo in future wars. In this war, there is active learning and aerial adaptation on both sides. Despite the significance of the Russian military’s summer resurgence, which prominently leveraged DJI UAVs, it might not be enough to offset the country’s early missteps, casualties, and conventional weapons attrition, especially amid ongoing international sanctions. There are signals that Russia is running out of key equipment and components, its recent contracts to receive Iranian Shahed-136 loitering munitions being a notable one. Whether Russia can overcome its early inertia amid these constraints remains unclear. Of particular concern is how these factors might affect the potential for nuclear escalation. The probability of a nuclear strike likely tracks with the degree of Russian desperation more generally. Insofar as incorporating commercial UAVs, which cannot carry a nuclear payload, improves the fighting capacity of military units, drone use should diminish the nuclear threat.

Ahead of future wars, militaries should analyze how small drones shape force structures, combined arms formations, and combat operations. Russia certainly will. This recommendation applies to militaries from the small to strong. Minor forces unable to field large, advanced air forces will find a flexible, reliable surrogate in increasingly advanced commercial drone models. Preponderant militaries, prone to rely on their exquisite platforms, should take note as well. The prevalence and persistence of multiple aerial assets that commercial technology enables affect the massing and maneuver of modern warfare assets. Fighters would do well to invest in, train on, and assimilate commercial aerial and counterdrone technologies that prepare them to maintain an edge in offense and defense.

The commercial drone phenomenon also has substantial implications for violent nonstate actors, such as insurgents, rebels, and terrorists. On average weaker and thus needing to be more innovative to surmount such shortcomings, these groups have long been the pioneers of the quadcopter phenomenon. Ukraine is a highly publicized proving ground for small drones. As ambitious onlookers in these organizations watch, they vicariously will learn, emulate, and innovate in other theaters. Consequently, there likely will be a burst of diffusion and creativity with drones for violent and illicit purposes. This is concerning because armed nonstate actors are not constrained by politics, norms, and laws like state militaries. They will not be shy to use small UAVs to their fullest multiuse potential to advance their agendas.

What is apparent is that the wartime benefits that commercial drones offer—intelligence, target designation, strike capacity, and propaganda and psychological effects—also can become assets for violent nonstate actors outside of warzones. This means that the threat extends into the national, local, and site-specific security domains, including such high-value targets as structures with symbolic importance, sensitive infrastructure, and population-centric venues. Stakeholders probably will look to apply new regulations where possible, whether on commercial platforms, component parts, or airspaces. This development probably will also lead to more counterdrone solutions and installations where stakeholders identify acute vulnerabilities.

A final corollary might come in the form of psychological reverberations. A Russian commercial drone pilot instructor has described the moral and psychological exhaustion of small UAVs in combat. Their appearance on the battlefield is a harbinger of harm, even if they are merely watching in the moment. Furthermore, soldiers develop phobias, always wondering if a drone is hovering nearby undetected.20 As aerial clips depicting the war’s grimness and fear continuously circulate, they could have residual effects in the public consciousness. If criminal or terroristic uses of drones proliferate beyond this war, which is likely, even a toy joyride might trigger public fear in some local communities.

The implications of drone use in Ukraine are likely to be long-standing, far-reaching, and multidimensional. Regulation and security challenges related to commercial UAVs were imminent before the war began, but the pointed and intensely watched application of this technology in Ukraine will amplify them. Keen observers will not repeat Russia’s mistake. They will take notes and adapt now, whether in doctrine, tactics, or defense.

ENDNOTES

1. This is a common lay term for unmanned aerial vehicles that this article uses interchangeably. Technically, drones also describe unmanned ground vehicles and unmanned aquatic platforms, submarine or surface, all of which are being used in the Russian-Ukrainian war but to a significantly lesser degree.

2. Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, “Do You Have a Drone? Put It to Use for the Experienced Pilots!” Facebook, February 25, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/MinistryofDefence.UA/posts/263895272589599.

3. Aila Slisco, “Ukraine Building 'Army of Drones' Though Donations to Monitor Front Line,” Newsweek, July 7, 2022.

4. John Spencer, “What Is Army Doctrine?” Modern War Institute, March 21, 2016, https://mwi.usma.edu/what-is-army-doctrine/.

5. Samuel Bendett, “Where Are Russia’s Drones?” Defense One, March 1, 2022, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2022/03/where-are-russias-drones/362612/.

6. Yana Dlugy, “Ukraine’s ‘Mosquito’ Air Force,” The New York Times, August 10, 2022.

7. David Axe, “Ukraine’s Drones Are Wreaking Havoc on the Russian Army,” Forbes, March 21, 2022.

8. Pyotr Skorobogaty, “Украина: гладиаторские бои” [Ukraine: Gladiatorial Fights], Центр прикладных исследований и программ [PRISP Center], August 4, 2022, http://www.prisp.ru/analitics/11005-skorobogatiy-ukraina-gladiatorskie-boi-0408.

9. Anonymous, “And by God It Worked,” Ukraine Volunteer Transcripts, November 5, 2022, https://ukrainevolunteer297689472.wordpress.com/2022/11/05/and-by-god-it-worked/.

10. Dmitry Astrakhan, “Drones in the Clear Sky: How Drones Change the Course of the SVO,” Izvestia, October 24, 2022, https://iz.ru/1414691/dmitrii-astrakhan/dron-sredi-iasnogo-neba-kak-bespilotniki-meniaiut-khod-svo (in Russian).

11. Nikita Yurchenko, “Vladimir Orlov, Veche: The Second Wave of Mobilization Is Inevitable—You Need Not 300 Thousand, but 2 Million," Interregional Public Organization “Veche,” November 21, 2022, http://veche-info.ru/news/9453.

12. Samuel Bendett, “To Robot or Not to Robot: Past Analysis of Russian Military Robotics and Today’s War in Ukraine,” War on the Rocks, June 20, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/06/to-robot-or-not-to-robot-past-analysis-of-russian-military-robotics-and-todays-war-in-ukraine/.

13. Buryatia Representatives, “The Budget of Buryatia Will Be Spent on Sights and Quadrocopters for a ‘Special Operation,’” Taiga.info, June 30, 2022, https://tayga.info/178163 (in Russian).

14. @rusfleet, “Notes of Midshipman Ptichkin: Cry for Copters,” Telegram, September 7, 2022, https://t.me/rusfleet/5304 (in Russian).

15. Dmitry Grigoriev, “Враг изощрен, но шансов нет. Как беспилотники помогают России в СВО” [The enemy is sophisticated, but there is no chance. How drones help Russia in SVO], Аргументы и факты, August 12, 2022, https://aif.ru/politics/world/vrag_izoshchren_no_shansov_net_kak_bespilotniki_pomogayut_rossii_v_svo.

16. Astrakhan, “Drones in the Clear Sky.”

17. Dmitry Astrakhan, “At the Moment Nothing Without Copters,” Izvestia, November 28, 2022, https://iz.ru/1432143/dmitrii-astrakhan/v-dannyi-moment-bez-kopterov-nikuda (in Russian).

18. TopWar Staff, “Концерн ВКО «Алмаз-Антей» запустил серийное производство многофункциональных беспилотников типа квадрокоптер” [Concern EKO ‘Almaz-Antey’ launched mass production of multifunctional drones of the quadrocopter type], Военное Oбозрение, October 26, 2022, https://topwar.ru/204047-koncern-vko-almaz-antej-zapustil-serijnoe-proizvodstvo-mnogofunkcionalnyh-bespilotnikov-tipa-kvadrokopter.html.

19. Kerry Chávez and Ori Swed, “The Proliferation of Drones to Violent Nonstate Actors,” Defence Studies 21, no. 1 (2021): 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2020.1848426.

20. Grigoriev, “Враг изощрен, но шансов нет.”

Kerry Chávez is an instructor in the political science department at Texas Tech University; project administrator at the university’s Peace, War and Social Conflict Laboratory; and a nonresident research fellow with the Modern War Institute at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.