The Cautious Nuclear Approach of Australia’s New Prime Minister

December 2022

By Aiden Warren

During 19 of the last 26 years in Australia, the conservative Liberal Party has been at the forefront of defining and cultivating the country’s foreign policy and its broader approaches toward global security. Not surprisingly, that has included maintaining a nonintrusive line in the arms control and nuclear nonproliferation domain.

Although Liberal leaders generally have advocated reductions in the numbers of nuclear weapons held by all nuclear-weapon states and adhered to Australian participation in the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), their approach has been somewhat paradoxical. In this regard, Australia has not forthrightly challenged the utility, value, legality, and legitimacy of nuclear weapons nor questioned the logic and practice of nuclear deterrence. Notwithstanding the 2021 pact among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States known as AUKUS, Australia has left nuclear agency predominantly in the hands of the states that possess nuclear weapons, compliantly accepting that this group can safely manage nuclear risks through appropriate adjustments to warhead numbers, nuclear doctrines, and force postures.

Although Liberal leaders generally have advocated reductions in the numbers of nuclear weapons held by all nuclear-weapon states and adhered to Australian participation in the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), their approach has been somewhat paradoxical. In this regard, Australia has not forthrightly challenged the utility, value, legality, and legitimacy of nuclear weapons nor questioned the logic and practice of nuclear deterrence. Notwithstanding the 2021 pact among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States known as AUKUS, Australia has left nuclear agency predominantly in the hands of the states that possess nuclear weapons, compliantly accepting that this group can safely manage nuclear risks through appropriate adjustments to warhead numbers, nuclear doctrines, and force postures.

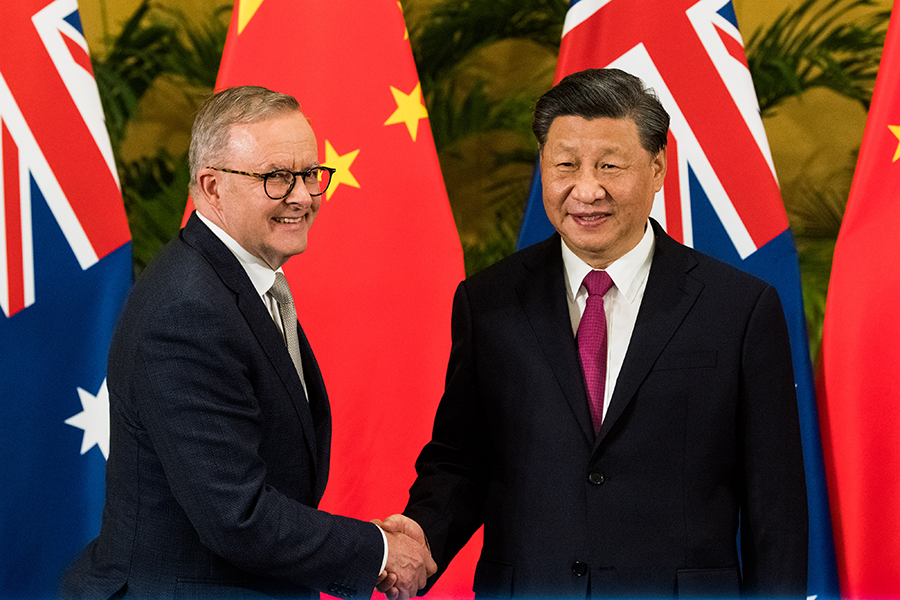

With the election of Anthony Albanese as prime minister in May 2022, Australia looked poised to move away from this hedging and somewhat pedestrian position to one that would embolden its nonproliferation efforts by proposing concrete new steps toward disarmament. Despite making bold proclamations while in opposition, however, the Albanese government’s position in its first year in office indicates that any movement toward a more progressive disposition on arms control and nonproliferation will be slow and very cautious. Evidence of that assessment can be found most clearly in the government’s approach to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) and implementation of the controversial AUKUS pact.

The TPNW

In late 2016, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution mandating the convening of a conference to negotiate a legally binding agreement that would prohibit nuclear weapons and ultimately lead to their total elimination. Reflecting the views of the Liberal Party, which was in power at that time, Australia did not embrace the treaty’s core premise that merely banning nuclear weapons would lead to their elimination. The Liberal government also did not believe that such a treaty would alter “the current, real, security concerns of states with nuclear weapons or those states, like Australia, that rely on extended nuclear deterrence as part of their security doctrine.” On this point, they argued that “disarmament efforts must engage all the nuclear-armed states and must focus on practical measures that recognize both the humanitarian and security dimensions of this issue.”1

To further underscore its position, the Liberal government did not take part in the UN conference to negotiate the ban treaty because it said that such a move did not offer a practical path to effective disarmament or enhanced security because key nuclear-armed states were not involved. Additionally, government officials contended that a ban treaty risked undermining the NPT, which Australia rightly regards as the cornerstone of the global nonproliferation and disarmament architecture. Because the TPNW stipulates parallel commitments to the NPT, officials argued that the ban treaty would create “ambiguity and confusion and would deepen divisions” between nuclear- and non-nuclear-weapon states.2

As stated by Australian Foreign Affairs Minister Julie Bishop in 2018,

The argument “to ban the bomb” may be emotionally appealing, but the reality is that disarmament cannot be imposed this way. Just pushing for a ban would divert attention from the sustained, practical steps needed for effective disarmament. The global community needs to engage those countries that have chosen to acquire nuclear weapons and address the security drivers behind their choices. They are the only ones that can take the necessary action to disarm.3

The TPNW evolved principally out of the sheer frustration felt by some states and nongovernmental disarmament organizations that the NPT was not effectively moving states toward a world without nuclear weapons. Although there has been significant reductions in the Russian and U.S. nuclear arsenals since the Cold War, it became evident in the early to late 2000s that the five nuclear-weapon states recognized under the NPT (China, France, Russia, the UK, and the United States) had not held up their end of the NPT bargain. Disarmament proponents highlighted the plans of nuclear-armed states to modernize their nuclear arsenals and argued that this trend clearly indicated that these states intended to maintain their stockpiles. For TPNW proponents, the accumulative effect of such modernization plans, coupled with the varying divisions within the NPT community, proved that the NPT had distinct limitations. Although the NPT imposed good faith obligations on nuclear-armed states, it left a legal gap to be addressed, namely that nuclear weapons need to be banned just as chemical and biological weapons are banned.4

The response of Australian policymakers toward the ban treaty has not been surprising and sits comfortably alongside the narrative and approach sponsored by many previous governments. In addition to complaints about the ban treaty “complicating matters,” there has been strong criticism about what signing the ban treaty would do to the Australian-U.S. alliance. According to Gareth Evans, foreign minister in a previous Labor-led government, “The difficulty for Australia in terms of signing or ratifying the ban treaty is that, to do so, we would effectively be tearing up our U.S. alliance commitment.”5 While in opposition, Richard Marles, the deputy prime minister and defense minister in the current Labor government, argued that the ban treaty raised “the prospect of Australia needing to repudiate our longstanding defense relationship” with the United States and “might undermine” the NPT and the ANZUS (Australia-New Zealand-United States) security agreement.6

Such views reveal a fundamental misunderstanding of the ban treaty in Australian foreign policy circles. One commentator, citing a paper published by the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School, has argued that in signing the ban treaty, Australia actually would advance its stated goal of pursuing nuclear disarmament without engendering insuperable legal complications to ongoing military relations with the United States. Moreover, Australia signed up to the treaties banning landmines and cluster munitions even though the United States still has not signed on. In other words, the alliance relationship does not bind Australia to include weapons of mass destruction in its defense policies.7 In 2018 it was clear that these sentiments had come into play when, on the last day of the 48th Australian Labor Party national conference, Albanese, then opposition stalwart, declared that if Labor won the 2019 Australian federal election, it would sign and ratify the TPNW. He gave assurances that his party would pursue a more assertive and “ambitious” approach, saying, “There’s a practical issue of how we bring those states, which are nuclear states, forward, so that this isn’t just a gesture…. [W]e want outcomes, that’s what we’re about as a political party. But one way in which you secure universality of support, in terms of a step towards that, is by Australia playing a role.”8

Labor leaders at the time believed that there was ample support for such a policy, with 78 percent of the federal caucus, 83 percent of Labor voters, and two dozen unions agreeing to endorse the ban treaty. Despite polls indicating that Labor was the hot favorite to win control of the government, it actually lost what was supposed to be the unlosable election to the Liberal Party’s Scott Morrison. With that definitive verdict, Albanese’s bold proclamations came to an abrupt halt.

Following the treaty’s global entry into force, the Labor Party reasserted its 2018 policy pledge on the TPNW at a platform conference in March 2021. Party branches in the states of South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria, and Western Australia, as well the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory, passed motions reinforcing the federal position. According to Albanese, Labor’s “carefully negotiated commitment” is consistent with its “values and our long history of advocacy on weapons of mass destruction.”9 When the party won control of government in the May 2022 national election, Albanese, as the newly minted prime minister, indicated that Australia would attend the UN meeting of states-parties to the ban treaty, which he had advocated in opposition and swore to ratify should Labor attain power.

As Albanese promised, Susan Templeman, a Labor member of Parliament from Macquarie, attended the first TPNW meeting of states-parties the following month as an observer. Her attendance was welcomed by the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), whose spokesperson said the group saw it as “recognition the newly-elected federal government is willing to engage with this critical meeting as a step towards signature and ratification” of the treaty.10

Yet, the new government made clear its cautious approach and its desire first to evaluate the legitimacy of the treaty’s verification and enforcement regime, its interface with the NPT treaty, and the extent to which states that signed the treaty proposed to bring together widespread support for the absolute ban. In this regard, the Albanese government wanted to be assured that such matters were addressed before it agreed to sign and ratify the treaty.11

Despite Albanese’s caution, the significance of the issue within the Australian political ranks was evident when, ahead of the TPNW meeting, 55 former Australian ambassadors and high commissioners, including Stephen FitzGerald, John McCarthy, Neal Blewett, and Natasha Stott Despoja, sent an open letter encouraging the prime minister to act promptly in meeting his preelection promise to sign and ratify the TPNW. “We hope…that Labor’s commitment to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons will be swiftly realized. Making meaningful gains in eliminating the most destructive weapons ever invented is as crucial for Australia’s security as it is for the security of people everywhere,”12 the letter stated.

There was strong popular support for such a move. An Ipsos poll in 2022 found that 76 percent of the public believed Australia should sign the TPNW, with 6 percent opposed, and 18 percent undecided. A range of actors within civil society also backed the treaty, including the Australian Medical Association, the Australian Red Cross, the Australian Council of Trade Unions, and more than 60 religious organizations. Local government councils in 40 Australian towns and cities, including Brisbane, Canberra, Hobart, Melbourne, and Sydney, also called on the government to sign and ratify the TPNW.13 In response, the government said that although it “shares the ambition of TPNW states-parties of a world without nuclear weapons,” it needed to take a thorough approach in examining a range of questions “to inform its approach to the TPNW.” Moreover, despite the government recently dropping its opposition to the ban treaty and shifting its voting position at the United Nations to “abstain” after five years of “no,” a prolonged, cautious approach of “consultation with partners, and civil society stakeholders” will remain par for the course.14

The AUKUS Pact

The other significant issue that will challenge the mettle of the Albanese government’s nuclear approach pertains to the controversial AUKUS pact. Announced in September 2021, the security partnership markedly redefined Australia’s middle-power status in the context of its role and capabilities in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond. Given the growing significance and frequency of Australian-U.S. ministerial consultation meetings over the last decade, the AUKUS pact in many ways can be perceived as yet another extension of Australia’s increasingly robust bilateral alliance with the United States. During the last five years in particular, the two countries clearly have decided that the Indo-Pacific strategic environment, dominated by competition with China, requires a more cooperative, unified approach that utilizes the shared defense technology and industrial bases of both states.

Not surprisingly, many of the concerns articulated by local and international experts during the AUKUS initiative’s first year will persist deep into Albanese’s tenure in office. The first controversial development emanating from it was the clumsy diplomacy demonstrated when Australia precipitously canceled its planned purchase of Attack-class submarines from France so that it could buy nuclear-powered submarines from the UK and the United States. Although the financial compensation for terminating this program—$568 million paid by Canberra to the French-owned Naval Group—has been settled and recent diplomatic visits to Paris by Albanese and Marles have quelled the acrimony, the total cost of the abandoned program will be approximately $2.3 billion. Aside from the economic fallout, many questions remain unanswered, including those relating to the logistics, gaps in capability, and extent to which Australia will be able to meet its NPT obligations.15 Additionally, Australia is a non-nuclear-weapon state; so its ability to own, operate, and fuel nuclear-powered submarines will have to comply with strict NPT requirements.

Not surprisingly, many of the concerns articulated by local and international experts during the AUKUS initiative’s first year will persist deep into Albanese’s tenure in office. The first controversial development emanating from it was the clumsy diplomacy demonstrated when Australia precipitously canceled its planned purchase of Attack-class submarines from France so that it could buy nuclear-powered submarines from the UK and the United States. Although the financial compensation for terminating this program—$568 million paid by Canberra to the French-owned Naval Group—has been settled and recent diplomatic visits to Paris by Albanese and Marles have quelled the acrimony, the total cost of the abandoned program will be approximately $2.3 billion. Aside from the economic fallout, many questions remain unanswered, including those relating to the logistics, gaps in capability, and extent to which Australia will be able to meet its NPT obligations.15 Additionally, Australia is a non-nuclear-weapon state; so its ability to own, operate, and fuel nuclear-powered submarines will have to comply with strict NPT requirements.

In the next few years, more information likely will come to the fore as the three AUKUS states turn from the consultation stage to the actual implementation of the pact. The depth and timing of such disclosures no doubt will continue to spur much discussion. Traditionally, the Australian defense industrial base has been dependent on the United States for key technologies. As such, Australian governments since 2017, including the Albanese government, have placed an important emphasis on working with the expanded U.S. national technology and industrial base, which is designed to promote a defense free trade area with some U.S. alliance partners, as well as leverage the Australian-U.S. Defense Trade Cooperation Treaty.

In a July 2022 speech, Marles underlined that one of the main goals of the AUKUS agreement was to “streamline processes and overcome barriers” in industrial cooperation. In undertaking this task, the Albanese government, he argued, would strive to improve its capacity to traverse the complicated U.S. defense export control regime, particularly U.S. Department of State regulations for international arms sales, with its requirements for security classifications and technology transfers. This would entail close dialogue with the U.S. Congress and agencies, such as the Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration on the submarines and the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security on export regulations for categories such as quantum technologies. Such increased cooperation has engendered much debate between those who argue that developments in the Indo-Pacific region necessitate these overtures and those who believe that they put Australia on a slippery slope to being inextricably tied to the U.S. military and its questionable security incursions.

Albanese will be in a better position to address lingering questions about the AUKUS pact when the government’s nuclear-powered submarine task force makes recommendations in March 2023. For instance, on a logistical level, the task force is expected to determine whether Australia will go with the UK Astute-class submarine, the U.S. Virginia-class nuclear submarine, or another version shared by all three states. The conclusions of this preliminary consultation phase should also illuminate the specific details of a submarine built domestically, what submarine the government proposes as an interim capability, and any additional proposals to address any AUKUS workforce requirements.

Albanese will be in a better position to address lingering questions about the AUKUS pact when the government’s nuclear-powered submarine task force makes recommendations in March 2023. For instance, on a logistical level, the task force is expected to determine whether Australia will go with the UK Astute-class submarine, the U.S. Virginia-class nuclear submarine, or another version shared by all three states. The conclusions of this preliminary consultation phase should also illuminate the specific details of a submarine built domestically, what submarine the government proposes as an interim capability, and any additional proposals to address any AUKUS workforce requirements.

In addition, the government’s defense strategic review, also due for release in early 2023, will convey how the AUKUS initiative is situated overall in Australia’s wider defense posture, preparedness, structure, and “looming capability gap.”16 The government will also articulate whether an interim, conventionally powered submarine fleet is required to address the chasm between the retirement of the Collins-class submarines and the development of the AUKUS nuclear-powered vessels.

In this regard, several retired defense officials have cautioned that Australia needs a “son of Collins” fleet or else the state will be left in a vulnerable position, particularly given that AUKUS submarines will not be operational until the 2040s. Navy Chief Vice Admiral Mike Noonan has said that constructing a new class of submarines as an “interim” capability could not be ruled out: “I think we’re going to see a period of study and reflection and we’re going to look at all options, so I don’t rule out any decision that our government might make with respect to realising our future navy capabilities.”17

Aside from these issues, what is missing in Albanese’s approach thus far is more clarity regarding proliferation concerns, which have resonated at home and abroad. A group of crossbench independents remain hesitant about the AUKUS pact, while the Australian Greens Party, in particular, has disagreed vehemently with the procurement of nuclear-powered submarines, or what they have termed “floating Chernobyls.” There are fears that introducing nuclear-powered submarines into Australia, a non-nuclear-weapon state, could prompt other non-nuclear-weapon states to acquire such a technology. This could trigger an arms race while increasing threat perceptions and security risks associated with Australia’s procurement of Tomahawk cruise missiles for the future submarines, particularly with regard to China. In the United States, some Democratic members of Congress also have raised concerns about the impact such developments could have on nonproliferation precedents.18

Many critics have questioned the utility of acquiring nuclear-powered submarines.19 Such vessels are regarded principally as a means of extending power at a distance, where they can operate near to China’s coast in conjunction with U.S. war-fighting strategies, instead of protecting Australia’s own coastline. A continued reliance on conventionally powered submarines is perceived to be a more suitable, cost-efficient strategy.

Additionally, some commentators and analysts have argued that obtaining nuclear submarines could necessitate a greater investment in a range of associated activities: more nuclear engineers, more applicable infrastructure, more logistical coupling, and further nuclear-military intermingling with the UK and the United States. Notwithstanding the growing anxieties about an increasingly assertive China, the majority of the Australian public is still disinclined toward nuclear weapons and nuclear power. The general populace also is concerned that the argument for nuclear-powered submarines could be skewed to soften up popular sentiment toward the eventual basing or storage of nuclear weapons on Australian territory.

The most pressing debate, however, has been the specific proliferation questions presented by the prospect of nuclear-powered submarines. Australia has been a consistent proponent of nuclear nonproliferation efforts, including domestic and international programs to reduce and remove weapons-usable highly enriched uranium (HEU) from civilian uses worldwide, and it claims to support a fissile material cut-off treaty. Even so, each submarine could contain approximately 20 nuclear weapons’ worth of HEU.20 Such a large cache of weapons-usable material could undermine Australian nonproliferation efforts and fissile material security if it is not subject to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards and inspections. Although using low-enriched uranium (LEU) as an alternative in the submarines would present a lower proliferation hazard than the existing HEU plan, nuclear-powered vessels and their accompanying nuclear infrastructure still raise other environmental, health, radioactive waste, accident, and proliferation risks. As a result, critics contend that the spread of any naval nuclear propulsion would be dangerous.

One issue to be addressed pertains to the further development of naval nuclear reactors and the Paragraph 14 loophole in the IAEA Model Safeguards Agreement Albanese needs to articulate in greater detail and nuance how he aims to maintain and even strengthen the effectiveness and efficiency of the IAEA safeguards system and not weaken it through the acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines. Additionally, in the context of the NPT, what will the military-to-military transfer of HEU to a non-nuclear-weapon state such as Australia mean for IAEA verification? Surely this could open the pathway for other non-nuclear-weapon states, some with potential proliferation motives, to obtain nuclear materials and to evade adherence to safeguards.21

Lastly, the Labor government, much like its Liberal predecessor, has said little regarding Australia’s South Pacific neighbors who have not been a factor in the recent nuclear-related discussions even though the humanitarian impacts of past nuclear tests and other nuclear activities remain a serious concern for them. Some Pacific leaders have argued that the AUKUS agreement undermines the Pacific community’s deep commitment to keeping the region nuclear-free. It also has spurred proliferation and political concerns among some of Australia’s closer neighbors in Southeast Asia.

A Disappointing Start

Albanese promised that his election as prime minister would deliver a more robust Australian commitment to nonproliferation, but his government’s first seven months in office have been somewhat disappointing, revealing a cautious, incremental approach that falls short of the challenge. Given that key nuclear-weapon states are busily modernizing and in some instances increasing their armories instead of dismantling them, many Australians have become disillusioned with the NPT and are pushing ratification of the TPNW with its absolute ban on nuclear weapons. Notwithstanding his government’s observer participation at the TPNW meeting in May, Albanese’s wait-and-see approach appears in stark contrast to the promising progressive words espoused before he was in a position of power.

In terms of the AUKUS pact, the discussion and scoping stage is now shifting toward the implementation phase. How the Albanese government responds to the findings of the task force and the defense review in early 2023 will determine the options for future Australian governments. Uncertainties persist as to the scale, budget, timeline, and significance of the AUKUS pact. All this makes 2023 a critical year for the Labor government.22

Commentators have explicitly highlighted the government’s general lack of discussion and transparency on these and other seminal issues: the diplomatic falling-out with France; the expanding cost of reneging on the French submarine deal; the likely cost to obtain nuclear submarines from the UK or the United States; the prospect of nuclear mishaps and their environmental ramifications; the disrupting capacity that the AUKUS pact might present to the Indo-Pacific region, particularly when diplomatic nuance, rather than military responses to China, needs to remain at the fore; and the concern of several of Australia’s neighbors whose sensitivities to nuclear issues have been disregarded. On all these matters, Albanese and Marles have walked a careful, minimalist line in terms of treatment and explanation.

Although it can be argued that it is too early to assess Albanese’s performance on the nuclear disarmament portfolio, indications suggest that incrementalism likely will remain his preferred approach. Such a missed opportunity would be tragic, especially when Albanese once espoused a more ambitious and hopeful vision of a world far less dependent on nuclear weapons.

ENDNOTES

1. Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “Steps Towards a Nuclear-Weapons-Free World,” 2018.

4. Shanelle Van, “Revisiting the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” Lawfare, November 27, 2018, https://www.lawfareblog.com/revisiting-treaty-prohibition-nuclear-weapons.

5. Paul Karp, “Labor Set for Nuclear Showdown as Gareth Evans Warns of Risk to US Alliance,” The Guardian, December 17, 2018.

6. Richard Lennane, “Shadow Ministers’ Move on Nuclear Ban Treaty,” Australian Institute of International Affairs, October 25, 2018, https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/shadow-ministers-move-on-nuclear-ban-treaty/.

7. Gem Romuld, “Labor Sets the Right Course on Nuclear Disarmament,” The Sydney Morning Herald, December 27, 2018.

8. Anthony Albanese, “Speech to the 48th National Conference of the Australian Labor Party Moving Support for the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty Adelaide Convention Centre, Sa,” n.d., http://anthonyalbanese.com.au/speech-moving-support-for-the-nuclear-weapon-ban-treaty-tuesday-18-december-2018.

9. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), “Australia’s New Prime Minister Is a TPNW Champion,” May 21, 2022, https://www.icanw.org/tpnw_albanese.

10. “MP Susan Templeman Represents Australia at Landmark Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty in Vienna,” Blue Mountains Gazette, June 26, 2022.

11. Ben Doherty, “Australia Yet to Sign Up to Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapons but Will Attend UN Meeting as Observer,” The Guardian, June 19, 2022.

13. ICAN, “Australia,” n.d., https://www.icanw.org/australia (accessed November 19, 2022).

15. Peter K. Lee and Alice Nason, “365 Days of AUKUS: Progress, Challenges and Prospects,” United States Study Centre, September 14, 2022, https://www.ussc.edu.au/analysis/365-days-of-aukus-progress-challenges-and-prospects.

17. Andrew Greene, “AUKUS Nuclear Submarine Plan to Be Revealed by March 2023,” ABC News, June 28, 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-06-29/richard-marles-defence-projects-submarines-aukus/101190876.

18. Lee and Nason, “365 Days of AUKUS.”

19. Hugh White, “From the Submarine to the Ridiculous,” Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, September 18, 2021, https://sdsc.bellschool.anu.edu.au/news-events/news/8191/submarine-ridiculous.

20. Alan Kuperman, “Opinion: Bomb-Grade Uranium for Australian Submarines?” Kyodo News, November 11, 2021, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2021/11/006a0287253b-opinion-bomb-grade-uranium-for-australian-submarines.html.

21. Marianne Hanson and Gem Romuld, “Introduction,” in Troubled Waters: Nuclear Submarines, AUKUS and the NPT, ed. Gem Romuld (ICAN, Australia, July 2022), pp. 2–5, https://icanw.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Troubled-Waters-nuclear-submarines-AUKUS-NPT-July-2022-final.pdf.

22. Lee and Nason, “365 Days of AUKUS.”

Aiden Warren is a professor of international relations at RMIT University in Melbourne and an Arms Control Association Fulbright Scholar alumnus.

This article was corrected online Jan. 3, 2023, to reflect these changes: Anthony Albanese was an opposition stalwart not its leader in 2018; endnote 11 should read Ben Doherty, not Brett Doherty; and the Labor Party came to power seven months ago, not nine months ago.