The Cuban Missile Crisis at 60: Six Timeless Lessons for Arms Control

October 2022

By Graham Allison

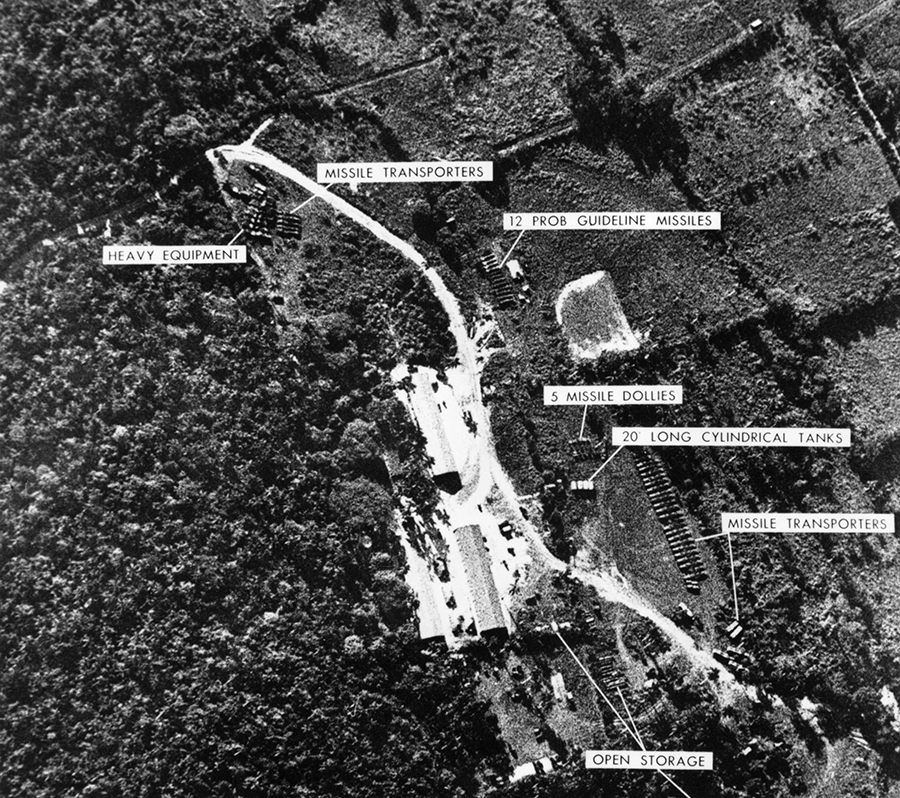

October marks the 60th anniversary of the most dangerous crisis in recorded history. In October 1962, U.S. President John Kennedy faced off with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in an eyeball to eyeball confrontation, each with his nation’s nuclear arsenal in hand. In the midst of the crisis, in a quiet aside with his brother, Kennedy offered his estimate that the risks of nuclear war were between one in three and even. Nothing that historians have discovered in the decades since has lengthened these odds. Had this crisis ended in nuclear war, hundreds of millions of people in the Soviet Union, the United States, and Europe could have experienced sudden death.

As the best documented major crisis in history, in substantial part because Kennedy secretly taped the deliberations in which he and his closest advisers were weighing choices they knew could lead to a catastrophic war, the Cuban missile crisis has become the canonical case study in nuclear statecraft. Over the decades since, key lessons from the crisis have been adapted and applied by the successors of Kennedy and Khrushchev to inform fateful choices. Of the many lessons from this nearly apocalyptic episode, six offer timeless insights for arms control.

As the best documented major crisis in history, in substantial part because Kennedy secretly taped the deliberations in which he and his closest advisers were weighing choices they knew could lead to a catastrophic war, the Cuban missile crisis has become the canonical case study in nuclear statecraft. Over the decades since, key lessons from the crisis have been adapted and applied by the successors of Kennedy and Khrushchev to inform fateful choices. Of the many lessons from this nearly apocalyptic episode, six offer timeless insights for arms control.

First, to survive in a world of mutually assured destruction or MAD, a nuclear power must constrain itself and find ways to persuade its nuclear adversary to constrain itself. MAD is the acronym used by Cold War strategists to capture the essence of objective conditions in which a nuclear power cannot attack an adversary that has a robust nuclear arsenal without triggering a response that destroys itself. Thus, even if country A can destroy country B totally, it cannot do so without B responding with an attack that destroys itself. A nation’s choice to attack an adversary that has a reliable second-strike nuclear arsenal is therefore functionally equivalent to a choice to commit national suicide. In these conditions, a nation’s survival requires it to coexist with its adversary since the alternative is to co-destruct.

Second, from the brute fact that “a nuclear war cannot be won” because at the conclusion the attacker would also have lost their own society, U.S. President Ronald Reagan drew a large categorical imperative: a nuclear war “must therefore never be fought.” Reagan’s often-repeated one-liner, that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must therefore never be fought,” almost says it all.

Reagan struggled with this radical, disruptive, profound truth. However good the United States was—very, he believed—and however evil the “Evil Empire” was, as he rightly named the Soviet Union, if these two deadly adversaries could not fight a nuclear war or a full-scale conventional war that would likely escalate to nuclear war, then what? Then, the whole character of their competition would have to be fundamentally different from relations between great powers through previous centuries. As Kennedy summarized his own attempt to internalize this fact, because “we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity.”

Lesson three spotlights the necessity for communication, especially private communication, between leaders of nuclear-armed states. Prior to the missile crisis, Kennedy and Khrushchev developed a back channel in which they exchanged private letters. During the crisis, U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy communicated secret messages from his brother the president to Khrushchev through the Soviet ambassador in Washington, Anatoly Dobrynin, including the terms of a secret deal that led to peaceful resolution of the crisis.

Yet, the technologies of the day through which these communications were transmitted took 11 hours. In a case where messages were being sent about urgent issues, such delay obviously risked catastrophe. Thus, immediately after the missile crisis, Kennedy proposed and Khrushchev accepted the establishment of the hotline that allowed direct, secret telephone communication between the leaders.

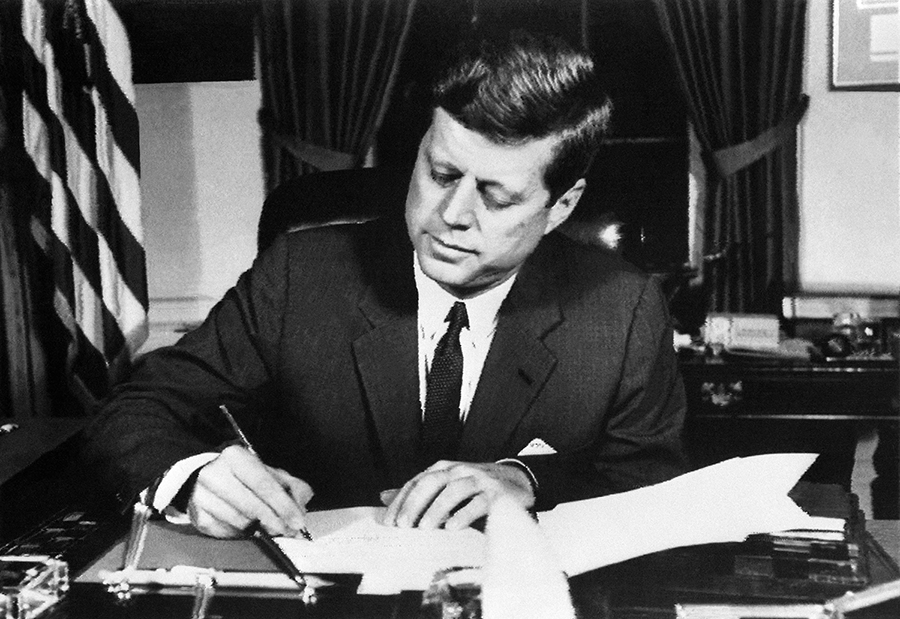

Kennedy believed that the most important lesson of the missile crisis was the necessity for mutual constraints, which he understood required unilateral constraints. In the major foreign policy speech of his career, the American University commencement speech given five months before he was assassinated, Kennedy highlighted what he identified as the central takeaway from the missile crisis: “Above all, while defending our own vital interests, nuclear powers must avert those confrontations which bring an adversary to a choice of either a humiliating retreat or a nuclear war.” This meant avoiding repeats of confrontations like the Cuban missile crisis because if there was a one-in-three chance of nuclear war in that case and if this game of nuclear Russian roulette were replayed repeatedly, the likelihood of nuclear war would approach certainty.

Kennedy believed that the most important lesson of the missile crisis was the necessity for mutual constraints, which he understood required unilateral constraints. In the major foreign policy speech of his career, the American University commencement speech given five months before he was assassinated, Kennedy highlighted what he identified as the central takeaway from the missile crisis: “Above all, while defending our own vital interests, nuclear powers must avert those confrontations which bring an adversary to a choice of either a humiliating retreat or a nuclear war.” This meant avoiding repeats of confrontations like the Cuban missile crisis because if there was a one-in-three chance of nuclear war in that case and if this game of nuclear Russian roulette were replayed repeatedly, the likelihood of nuclear war would approach certainty.

The fifth lesson requires that adversaries find ways to constrain their own unilateral activities, including in explicit agreements, as the price for inducing their adversary to accept mutual restraints. Thus began what has been known in the decades since as arms control. Kennedy’s unilateral announcement that the United States was ending all nuclear testing in the atmosphere challenged the Soviet Union to match it in kind. In fact, Khrushchev did. This was followed by negotiations that over time produced constraints on deployment of offensive nuclear weapons (the Strategic Arms Limitations Talks and the strategic arms reduction treaties) and defenses against ballistic missiles (the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty). Each of these treaties was in essence a bargain in which both nations agreed to forgo actions they would otherwise have taken in exchange for the other doing likewise.

Particularly for a state that identified itself as and truly was a superpower, the proposition that U.S. policymakers would forgo actions they felt advanced U.S. interests in exchange for an adversary forgoing actions that the United States judged threatening to its interests was almost unthinkable. Thus, for example, when Reagan agreed to eliminate U.S. intermediate-range nuclear-armed missiles as the price for Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev eliminating the Soviets’ intermediate-range nuclear-armed missiles, he was denounced by hawkish commentators.

The leading conservative intellectual of the time, William Buckley, devoted an entire issue of his National Review to condemning Reagan’s Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty as a “suicide pact.” Columnist George Will wrote in 1987 that “Reagan has accelerated the moral disarmament of the West—actual disarmament will follow.” About such criticism, Reagan observed, “Some of my more radical conservative supporters protested that in negotiating with the Russians I was plotting to trade away our country’s future security. I assured them we wouldn’t sign any agreements that placed us at a disadvantage, but still got lots of flak from them—many of whom, I was convinced, thought we had to prepare for nuclear war because it was ‘inevitable.’”

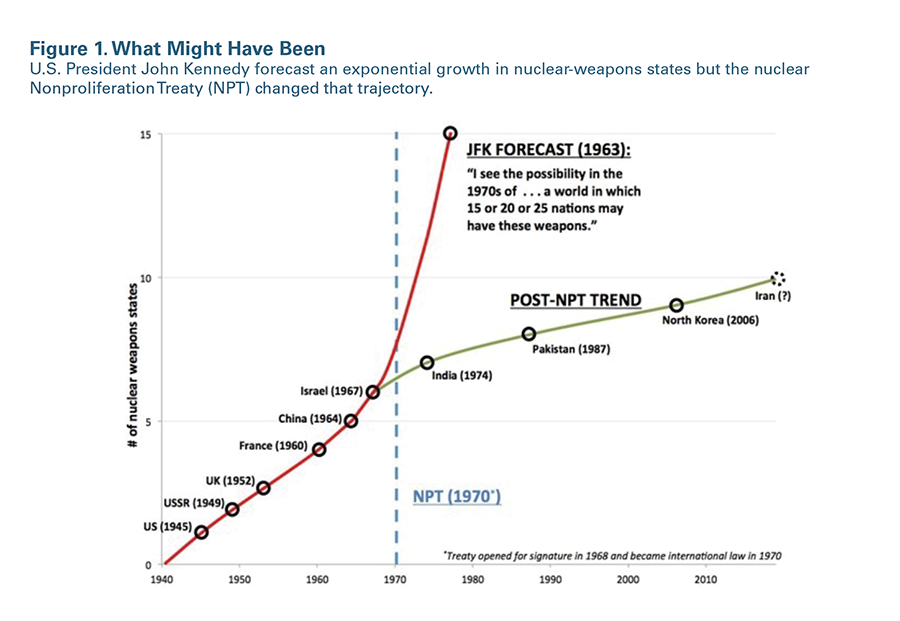

The sixth lesson recognizes that to avoid future confrontations like the Cuban missile crisis would require finding ways to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons to additional states. Kennedy was haunted by the specter of “the possibility in the 1970s of the president of the United States having to face a world in which 15 or 20 or 25 nations may have these weapons” (fig. 1). As he said, “I regard that as the greatest possible danger and hazard.”

To escape that future, the United States launched a series of initiatives that created the nonproliferation regime, the centerpiece of which is the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). In that treaty, non-nuclear-weapon signatories forswore nuclear weapons in exchange for other states, including their adversaries or potential enemies, making an equivalent pledge. In contrast to the 15 or 25 nuclear-weapon states that Kennedy envisaged, today just nine states have nuclear weapons.

Six decades on, the Cuban missile crisis remains a pivotal moment in arms control. Given the nightmare that could have been, the world can be grateful for generations of effort that literally bent this arc of history. Yet, given the pressures for further proliferation of nuclear weapons resulting from the lessons leaders are now drawing from Russia’s war against Ukraine, as well as the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the toppling of Libyan leader Moammar Gaddafi in 2011, sustaining this success will require another burst of strategic imagination and relentless effort in the decades ahead.