"[Arms Control Today] has become indispensable! I think it is the combination of the critical period we are in and the quality of the product. I found myself reading the May issue from cover to cover."

Breaking the Impasse Over Security in Space

September 2022

By Victoria Samson

As the international use of space has become more complicated since the end of the Cold War, multilateral discussions about ensuring the security of this shared domain have stalled because of circular arguments. Yet, the need to address this challenge is acute because space security continues to grow as a factor in overall global stability and, in fact, has become more relevant, given that many more countries are interested in the benefits that come from space assets and in counterspace capabilities.

A few statistics underscore this reality. As of August 2022, there are more than 6,400 active satellites in orbit, affiliated with more than 80 nations.1 The U.S. military is tracking 47,000 pieces of uncontrollable space debris that can disable or destroy satellites.2 A stable, predictable space environment serves all who get benefits from this domain, and because space is literally universal, it requires a shared global approach to achieve that outcome.

A few statistics underscore this reality. As of August 2022, there are more than 6,400 active satellites in orbit, affiliated with more than 80 nations.1 The U.S. military is tracking 47,000 pieces of uncontrollable space debris that can disable or destroy satellites.2 A stable, predictable space environment serves all who get benefits from this domain, and because space is literally universal, it requires a shared global approach to achieve that outcome.

Although this lack of progress in space security discussions in multilateral forums has become worrisome, there is some reason for optimism. In an effort to break the impasse, international diplomats and experts over the past several years have begun shifting from a traditional arms control approach that attempted to limit control of technologies through treaties or other legally binding approaches to a focus on behavioral, non-legally binding approaches to space security. Toward this end, an open-ended working group established by the United Nations is striving to identify norms of behavior and responsible actions in space, a process that could create room for new governance mechanisms to make space more stable and predictable. The wildcard is whether the working group participants, next scheduled to meet in Geneva on September 12–16, are prepared to approach the conversation in good faith and prioritize the group’s success over winning short-term political points against rivals.

Along with using space for national security missions, such as intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, missile tracking, military communications, and command and control, more countries are relying on it for economic development. Increasingly, they also are investigating ways in which to interfere with other countries’ access to or use of space assets. The Secure World Foundation launched a global counterspace threat assessment in 2018 by examining what was known publicly about the counterspace research, development, policies, and budgets of China, India, Iran, North Korea, Russia, and the United States.3 In 2020, France and Japan were added; the version released this April also included Australia, South Korea, and the United Kingdom, for a total of 11 countries.4

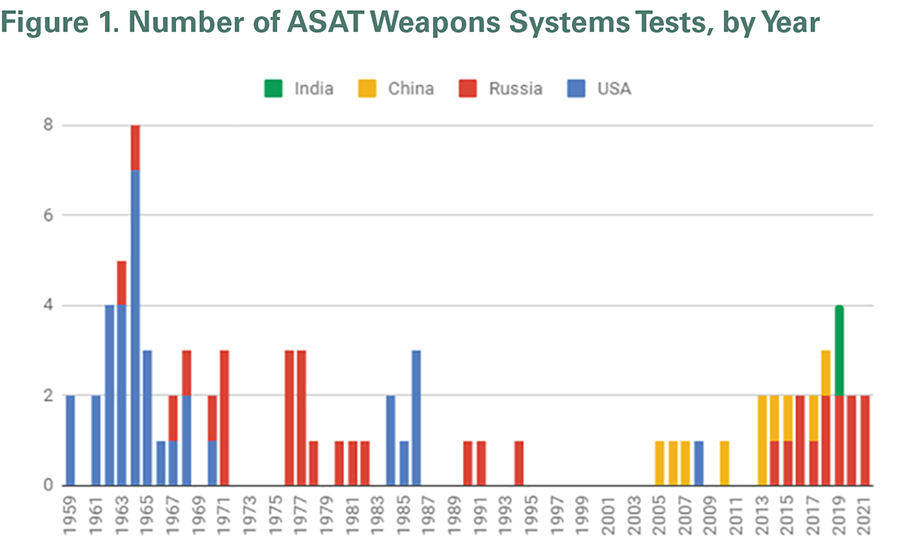

Although many countries are pursuing significant research and development programs involving a broad range of destructive and nondestructive counterspace capabilities, only nondestructive capabilities are actively being used in current military operations. There has been a recent uptick, however, in destructive anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons testing, which is concerning because such tests can result in long-lived debris that can harm other satellites in orbit. They also can establish the precedent that ASAT weapons tests are acceptable and thus encourage more countries to conduct them. That in turn runs the risk of inadvertent escalation or even possible deliberate use of ASAT weapons during a conflict if this proliferation becomes more prevalent.

During the Cold War, the only two countries to test ASAT weapons systems were the Soviet Union and the United States. There was a decade-long pause in these tests at the end of the Cold War, but they eventually resumed with the involvement of two more countries: China in 2005 and India in 2019. Over the past 17 years, there have been 24 tests by the four countries, out of a total of 80 tests conducted since the first one by the United States in 1959 (fig. 1).5

The security and stability of space has been a concern since the beginning of the Space Age. It is more acute now, however, because more than 80 countries have satellites in orbit and there is a rising dependence on space capabilities for such critical needs as economic development, environmental monitoring, and disaster management. Although space security had been perceived as important only to the geopolitical superpowers, nearly every person on the planet now uses space data in some way and thus benefits from a predictable space environment.

The security and stability of space has been a concern since the beginning of the Space Age. It is more acute now, however, because more than 80 countries have satellites in orbit and there is a rising dependence on space capabilities for such critical needs as economic development, environmental monitoring, and disaster management. Although space security had been perceived as important only to the geopolitical superpowers, nearly every person on the planet now uses space data in some way and thus benefits from a predictable space environment.

Given the security concerns related to space capabilities and the fact that space is a shared domain where the activities of one actor can affect the ability of all to utilize it, the United Nations is the natural organization to convene space security negotiations. Nevertheless, it has not generated any concrete results on this topic in years. One reason is a fundamental disagreement among geopolitical superpowers about the nature of the threat and managing it. China, Russia, and their allies have long focused on explicitly defined weapons systems placed in orbit that could threaten ground targets. They are concerned that a country would field space-based missile defense interceptors, with the assumption being that the United States would be the one to do this, even though it has no plans to deploy such interceptors or invest significantly in that capability. Such a threat definition reflects a traditional arms control approach focusing on a specific technology and designated weapons system that China and Russia consider destabilizing to space security.

China and Russia have opted to defend against this threat by promoting a treaty-based approach. In 2008, they released their draft Treaty on Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects, revamping it in 2014. It has not gotten much traction, given its lack of verification, its failure to address ground-based ASAT weapons systems, and the dual-use nature of space technology. The U.S. refusal, until recently, to offer an alternative also has stymied progress in multilateral discussions on space security.

The United States and its allies have considered the biggest threats to space security and stability to be behavior and actions in orbit. They argue that much of the same technology could have benign usage or bad intent, depending on the actions undertaken by the owner of that technology. The dual nature of much of the technology used for satellite capabilities and launching means it can have civilian or military applications, depending on the mission. That makes it difficult to use a traditional arms control approach in which the technology itself is limited from proliferating further. Instead, it is what is done with that technology that can be perceived as threatening. They assert that, in order to ensure a stable, predictable space environment, the best approach is to develop norms of behavior or identify responsible actions in orbit, because that would not be dependent on specific technology to be effective. There has not been general interest in a legally binding approach to space security, given that the last effective space treaties were negotiated in the mid-1970s.

In December 2020, the UK led a coalition of countries as sponsors of UN General Assembly Resolution 75/36.6 The resolution, which passed resoundingly, called for national submissions to UN Secretary-General António Guterres by May 2021 that would clarify how countries see threats to space security, identify responsible behavior in space, and suggest possible paths forward. The goal was to find commonalities that could break the impasse that for decades essentially had stopped progress in space security discussions in the Conference of Disarmament. Around 30 countries submitted responses, reflecting some convergence around the idea that the deliberate creation of space debris and the uncoordinated close approach to another country’s satellite are irresponsible.7

On the other hand, many countries identified acting with due regard and avoiding harmful interference, principles represented in Article IX of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, as responsible behavior. Some countries still pushed for a legally binding response to concerns about space security, but there seemed to be broader support for non-legally binding solutions. Based on the national submissions, Guterres generated a report summarizing the major ideas put forward and recommending an inclusive process to move the discussions forward at the UN General Assembly meeting in fall 2021.8

On the other hand, many countries identified acting with due regard and avoiding harmful interference, principles represented in Article IX of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, as responsible behavior. Some countries still pushed for a legally binding response to concerns about space security, but there seemed to be broader support for non-legally binding solutions. Based on the national submissions, Guterres generated a report summarizing the major ideas put forward and recommending an inclusive process to move the discussions forward at the UN General Assembly meeting in fall 2021.8

In December 2021, UK officials, again with a strong coalition of co-sponsors, secured adoption of Resolution 76/231, which called for establishing an open-ended working group that would work on “reducing space threats through norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviour.”9 It is similar to another type of UN entity, the group of governmental experts, in that both are given a very specific mandate and have the goal of producing a final report that is based on consensus. The crucial difference is participation: an open-ended working group is open to all UN member states and sometimes civil society organizations or other relevant actors, with the mission of making the process as inclusive as possible. If the goal is to reach agreement on responsible behaviors in space that reflect the needs of the global community, not just one category of space actors, and to ensure that the approved norms do not unduly burden new actors in space, it is important to represent as many perspectives as possible in the discussions.

This commitment to inclusivity was a lesson learned from the failure of the European Union’s draft International Code of Conduct, which was perceived by non-Western actors as a preexisting document in which they had no input. Similarly, a group of governmental experts met in 2018–2019 to discuss elements of a potential legally binding instrument for the prevention of an arms race in outer space. Due to UN criteria, however, it limited participation to 25 member states. Even so, it failed to reach consensus on its report.

The open-ended working group on space has been tasked to meet twice each in 2022 and 2023 and given the mandate to examine the existing legal and normative framework regarding space threats arising from behavior, discuss threats to space systems and irresponsible actions, and recommend norms, rules, and principles of responsible behavior in space. The report is due to be submitted to the General Assembly in the fall of 2023.10 The resulting norms could then be used as launchpads for UN resolutions. Further down the line, they could even be the basis of legally binding agreements.

The first working group meeting was scheduled for mid-February 2022, but at the planning session the preceding week, it became apparent that there was resistance to holding the group meeting as planned. Countries that voted no on the resolution creating the working group suspected that the whole process was meant to end-run the Chinese-Russian treaty proposal. They argued that the roughly six weeks since the passing of Resolution 76/231 had not given the international community sufficient time to prepare. Recognizing the futility of a diplomatic negotiation in such a situation, the working group chair, Hellmut Lagos Koller of Chile, postponed the first meeting until May amid hopes that that would give interested parties sufficient preparation time.

In the interim, the United States announced that it was committing not to conduct destructive direct-ascent ASAT missile tests.11 This decision reflected how the United States and like-minded nations are approaching space security issues, with a focus on behavior, not capabilities, and on achieving a non-legally binding agreement instead of a formal treaty. Even so, U.S. officials have not ruled out the possibility that this unilateral commitment could eventually evolve into a treaty.

The impetus for the commitment not to conduct ASAT weapons tests was concern regarding the long-lived debris that the tests created. It was foreshadowed in U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s July 2021 memo that spelled out five tenets of responsible behavior in U.S. Department of Defense space operations, including limiting the generation of long-lived debris.12

The debris issue also was brought up in December 2021 at the first meeting of the National Space Council, where the Biden administration released its space priorities framework. In remarks at that event, Vice President Kamala Harris criticized the ASAT weapons test conducted by Russia one month earlier that created more than 1,500 pieces of trackable debris, and Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks stated that the Defense Department “would like to see all nations agree to refrain from antisatellite weapons testing that creates debris.”13 Even with this intellectual underpinning, the decision to halt ASAT weapons testing was a big change in that the United States was voluntarily and proactively restricting the possibility of future destabilizing actions in orbit. For many years, the national security establishment had looked askance at anything less than complete freedom of action for the United States in space.

The U.S. testing announcement led the way to the first meeting of the UN space working group in Geneva three weeks later. There was some trepidation beforehand that those who opposed the group’s creation might cause procedural interruptions or otherwise limit discussion, but the meeting went surprisingly smoothly. The one exception was a brief walkout by Western countries when a Russian diplomat used inflammatory language about the Ukrainian government. Mostly, the participating countries seemed invested in having a general exchange of views and discussing speaker presentations on the international legal and normative framework concerning threats arising from state actions.

Underlining the inclusivity for which organizers were hoping, a wide variety of state actors participated in the discussions while civil society representatives listened from the sidelines and made their own statements when time permitted.

The Canadian delegation kicked off the first day of the meeting with the surprising announcement that Canada too would make a commitment not to conduct destructive ASAT missile tests.14 This commitment was endorsed by more than a dozen countries, and Brazil even called for a complete moratorium on all ASAT weapons tests. No other countries officially joined the United States and Canada in this pledge at that time, although New Zealand did in June 2022.15 During the working group meeting, the United States made clear that it hoped moratoriums would become a broadly endorsed norm and be incorporated into whatever principles of responsible behavior might make it into the final working group report.

The focus will shift to threats to space security when the working group opens its next meeting on September 12 in Geneva. It is possible that this week-long session could be more turbulent than the last one given the divisions among the geopolitical superpowers over what threatens space security and stability, particularly concerns that a process centered on non-legally binding norms of behavior will supplant a legally binding approach.

None of this means that the working group is doomed to failure. Simply holding these discussions is broadening awareness globally about the complicated structure of space security and the ways in which the multilateral process can shore it up. Many states without experience in these topics are developing their knowledge and capacity to participate in these discussions and are doing so in an increasingly sophisticated manner that is moving the debate forward. For example, the Philippines introduced a paper about the principle of due regard and its role in responsible space behavior at the May working group meeting.16

The content of the discussions is illuminating too, reflecting a spectrum of responses in terms of what activities countries perceive to be destabilizing in space, what they deem responsible behavior to be, and how those involved in space should be held accountable for their actions. Whether the international community comes to agreement on any of this, it is helpful from a transparency perspective to have these beliefs spelled out and made public.

Although it is not guaranteed that there will be universal agreement on the norms and principles to be included in the final working group report, it is likely that there will be broad concurrence on at least some norms of responsible space behavior. There is nothing preventing countries from taking what they have found useful in these group discussions and incorporating them unilaterally in their space activities, independent of the UN process. In addition, these norms could become the foundation of future UN resolutions and, if widely disseminated, could even lead to legally binding agreements. For example, more states could formalize commitments not to conduct destructive ASAT missile tests. Although some question the benefit of such a pledge, there is power behind it. Even countries that cannot conduct missile tests or never had any intention of doing so can demonstrate that they find such behavior irresponsible due to the unpredictable nature and potential damage of the debris generated. That is how the norm can be formalized and gain acceptance until one day it becomes customary international law. Of course, countries that have tested ASAT weapons systems can reinforce future stability and security by making this pledge as well.

There are other actions states can take and include in the working group report to advance transparency and accountability for activities in orbit while not being too restrictive or burdensome. These include underlining their commitments to the existing legal framework for space activities, such as signing and ratifying the Outer Space Treaty, the Liability Convention, and the Registration Convention; registering space objects, including military ones, with the UN in a timely manner; and providing information about activities in space, including, when possible, military satellite behavior, such as satellite launch notifications, planned satellite maneuvers, and potential close approaches to other satellites.

They could also commit to creating and publicizing protocols guiding uncoordinated close approaches to other countries’ satellites; publishing information about national budgets, policies, and programs related to space; agreeing not to interfere with national technical means of verification; and engaging in best practices to mitigate the creation of space debris.

In short, this working group has the potential to move discussions off the hamster wheel of the treaty/no treaty debate on which the international community has been stuck for years. The group will not be able to resolve all security concerns about space, because no single solution or approach can do that; but it could make progress on some of the most pressing challenges, helping make space safer, more stable, and more predictable for all.

ENDNOTES

1. CelesTrak, “SATCAT Boxscore,” August 10, 2022, https://celestrak.org/satcat/boxscore.php.

2. Sandra Erwin, “Tracking Debris and Space Traffic a Growing Challenge for U.S. Military,” SpaceNews, August 9, 2022, https://spacenews.com/tracking-debris-and-space-traffic-a-growing-challenge-for-u-s-military/.

3. Brian Weeden and Victoria Samson, eds., “Global Counterspace Capabilities: An Open Source Assessment,” Secure World Foundation, April 2022, https://swfound.org/media/207350/swf_global_counterspace_capabilities_2022_rev2.pdf.

5. “Anti-Satellite Weapons,” Secure World Foundation, n.d., https://swfound.org/media/207392/swf-asat-testing-infographic-may2022.pdf.

6. UN General Assembly, “Reducing Space Threats Through Norms, Rules and Principles of Responsible Behaviours,” A/RES/75/36, December 16, 2020.

7. UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA), “Report of the Secretary-General on Reducing Space Threats Through Norms, Rules and Principles of Responsible Behaviors (2021),” n.d., https://www.un.org/disarmament/topics/outerspace-sg-report-outer-space-2021/ (accessed August 12, 2022).

8. UN General Assembly, “Reducing Space Threats Through Norms, Rules and Principles of Responsible Behaviors: Report of the Secretary-General,” A/76/77, July 13, 2021.

9. UN General Assembly, “Reducing Space Threats Through Norms, Rules and Principles of Responsible Behaviors,” A/RES/76/231, December 30, 2021.

10. UNODA, “Open-Ended Working Group on Reducing Space Threats: Overview,” n.d., https://meetings.unoda.org/meeting/oewg-space-2022/ (accessed August 12, 2022).

11. The White House, “Fact Sheet: Vice President Harris Advances National Security Norms in Space,” April 18, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/04/18/fact-sheet-vice-president-harris-advances-national-security-norms-in-space/.

12. Lloyd J. Austin to secretaries of the military departments et al., “Tenets of Responsible Behavior in Space,” memorandum, July 7, 2021, https://media.defense.gov/2021/Jul/23/2002809598/-1/-1/0/TENETS-OF-RESPONSIBLE-BEHAVIOR-IN-SPACE.PDF.

13. Marcia Smith, “Space Council Condemns Russian ASAT Test, DOD Calls for End to Debris-Creating Tests,” SpacePolicyOnline.com, December 1, 2021, https://spacepolicyonline.com/news/russian-asat-test-draws-more-condemnation-from-national-space-council-dod-wants-to-end-debris-creating-tests/.

14. Jeff Foust, “Canada Joins U.S. in ASAT Testing Ban,” SpaceNews, May 9, 2022, https://spacenews.com/canada-joins-u-s-in-asat-testing-ban/.

15. Mike Houlahan, “Mahuta’s Satellite Test Pledge Launches Policy School,” Otago Daily Times, July 2, 2022, https://www.odt.co.nz/news/dunedin/campus/mahuta%E2%80%99s-satellite-test-pledge-launches-policy-school.

16. UN General Assembly, “The Duty of ‘Due Regard’ as a Foundational Principle of Responsible Behavior in Space: Submitted by the Republic of the Philippines,” A/AC.294/2022/WP._, May 6, 2022 (advanced and unedited version).