"No one can solve this problem alone, but together we can change things for the better."

Congressional Support Needed for Success

July/August 2021

By Jessica J. Lee

Any successful North Korea policy must include cooperation from Congress. Although President Joe Biden seems open to a negotiated solution to the growing North Korean nuclear threat, he has offered little information on how he plans to work with the deeply fractured U.S. legislative branch to support his policy. Without congressional backing, Biden is unlikely to take the decisive action needed to get the North Koreans interested in returning to talks, such as declaring a formal end to the 1950–53 Korean War and offering Pyongyang security guarantees in exchange for verifiable steps toward reducing its nuclear weapons.

In short, congressional buy-in is central to the administration’s ability to execute an effective North Korea strategy, one that puts concrete offers on the table rather than waiting for Pyongyang to take the highly unlikely first step of giving up all of its nuclear weapons.

In short, congressional buy-in is central to the administration’s ability to execute an effective North Korea strategy, one that puts concrete offers on the table rather than waiting for Pyongyang to take the highly unlikely first step of giving up all of its nuclear weapons.

Biden’s North Korea Policy

Biden came into office committed to making diplomacy the centerpiece of U.S. foreign policy. No single issue will test that resolve more than North Korea, which experts estimate possesses between 40–50 nuclear weapons.1

Two months after Biden was elected president, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un pledged to develop even more advanced nuclear capabilities as a deterrence against its “biggest enemy,” the United States. Yet, North Korea’s quest for nuclear weapons as a security guarantee has long posed a wide range of challenges for the United States, its allies, and the region.

In 2017, North Korea conducted its sixth nuclear test, which was large enough to have been a hydrogen bomb. Pyongyang has twice tested intercontinental ballistic missiles with ranges that could reach the United States. It also has the world’s fourth-largest military, with more than 1.2 million personnel, and is believed to possess chemical and biological weapons.

There is growing acceptance within the policy community in the United States that Pyongyang has nuclear capabilities that are so advanced that it is no longer vulnerable to U.S. leverage and pressure, that it is unlikely to ever give up its arsenal, and that an arms control agreement to verify and monitor the North’s weapons is the most realistic pathway forward.2 The idea would be to cap the North’s arsenal to stop it from further destabilizing the region, while maintaining the long-term goal of complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.

On April 30, when the White House announced the completion of its North Korea policy review, press secretary Jen Psaki described the goal as a “complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.” It would seek “practical progress that increases the security of the United States, our allies, and deployed forces,” not through a grand bargain or strategic patience but through a “calibrated and practical” strategy, she said.3

That same day, the Washington Post quoted a senior administration official as saying, “[W]e do not think what we are contemplating is likely to forestall provocation from the North,” and that the administration “fully intends to maintain sanctions pressure while this plays out.”

At their May 21 summit, Biden and South Korean President Moon Jae-in issued a joint statement with additional details. It stressed diplomacy and affirmed commitments in the 2018 Panmunjom Declaration between South Korea and North Korea and in the 2018 Singapore Joint Statement signed by President Donald Trump and Kim as being “essential to achieve the complete denuclearization and establishment of permanent peace on the Korean peninsula.”4 The May statement also noted Biden’s support for “inter-Korean dialogue, engagement, and cooperation,” and his commitment to address the human rights and humanitarian needs inside North Korea.

Based on publicly available information, the administration’s North Korea policy hits all the right notes. The question is whether it is concrete enough for members of Congress to support.

Congressional Involvement on North Korea

The recent history of congressional involvement on North Korea policy is fraught with misaligned executive-legislative branch expectations. After Republicans gained the majority in Congress in 1994, they obstructed the deal reached by President Bill Clinton and North Korean leader Kim Jong Il known as the Agreed Framework. Critics accused Clinton of being soft on Pyongyang, but Republicans did not offer any alternatives to the Agreed Framework’s freeze on North Korea’s development of nuclear weapons in exchange for energy assistance. Eventually, their opposition enabled hard-liners in the next administration, led by President George W. Bush, to kill the Agreed Framework altogether.

Intelligence agencies also played a role in the agreement’s demise. Five years after the framework was signed in 1994, the Defense Intelligence Agency asserted North Korea was building a secret nuclear-related facility at Kumchang-ri in violation of the agreement. Joel Wit, who led the U.S. inspection of the alleged nuclear facility, noted that “the most important lesson from Kumchang-ri is that verifying a denuclearization deal between Washington and Pyongyang will be impossible without trust-building and reconciliation between the two countries.”5 Although the United States ultimately determined that Kumchang-ri was not a nuclear facility, the dispute generated enough controversy and bad feeling to scuttle the agreement.

Not all congressional involvement related to North Korea has been obstructionist. Some of it was motivated by a genuine interest in fostering trust and deepening understanding between the two countries. For example, in August 1997, a bipartisan, seven-member congressional delegation led by House Intelligence Chairman Porter J. Goss (R-Fla.) visited Pyongyang, the first lawmakers ever to do so. The delegation expressed “bipartisan support for United States policy to encourage North Korea to engage in honest and good faith negotiations to lessen tensions in the region” and confirmed that “opportunity for further constructive dialogue exists.”

In May 2003, another bipartisan delegation made the trip, led by Representative Curt Weldon (R-Pa.), thus culminating an 11-month effort by Weldon to visit North Korea for the purpose of “engaging senior [North Korean] officials in informal discussions, free of the formality of traditional posturing and imposed pressures of negotiation objectives, to share mutual perspectives on the major political, military, and economic issues.”6

No matter how one feels about the regime in Pyongyang, diplomacy must be an essential component of policy, even if members of Congress do not always admit it. Traveling to the country can offer insights that can lead to breakthroughs. For example, a member of the 2003 delegation, Representative Joe Wilson (R-S.C.), described North Korea as the “most totalitarian dictatorship ever devised,” but still expressed support for “the efforts of President Bush to seek a peaceful solution with North Korea that will eliminate the nuclear threat and save innocent North Korean civilians from tragedy.”7

COVID-related travel restrictions and border closures make congressional visits to North Korea unlikely for the foreseeable future. Yet the underlying premise for these visits remains valid. Direct talks at all levels are needed to understand both sides’ motives and should be resumed when possible. The absence of trust between Americans and North Koreans is a major barrier to progress on the nuclear or political front. Without trust, no agreements can survive across administrations, as Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal proved. The United States needs to understand what drives the decisions of North Korea’s leadership so that miscalculations do not flare into war. Similarly, Pyongyang could misread comments from various political leaders in Washington without multifaceted communication channels.

The Need for Constructive Engagement

Biden’s North Korea policy has something for everyone, which is a strength and a weakness when it comes to likely congressional reaction. The administration has pledged to be “calibrated and practical,” perhaps in recognition of the growing chorus among North Korea experts who favor a practical, interim deal to halt and monitor North Korea’s nuclear weapons program prior to complete denuclearization.

In expressing support for the 2018 Singapore statement, the administration gave a nod to these experts who advocate for a political settlement between the United States and North Korea that would declare an end to the Korean War and establish diplomatic relations between the two countries, with a long-term goal of signing a peace treaty to be ratified by two-thirds of the U.S. Senate. The aim should be to pursue this political settlement in parallel with a phased denuclearization process that in the short-term seeks to limit North Korea’s nuclear force and reduce proliferation risks while maintaining the long-term goal of a nuclear weapons-free Korean peninsula. At the same time, the administration plans to maintain sanctions pressure while diplomacy plays out, a nod to hawks on Capitol Hill who prefer coercive tools as the main vehicle for changing North Korea’s behavior.

In the coming months, members of Congress will look for opportunities to make their mark on North Korea policy, especially if there is an absence of leadership from the White House. The first legislative vehicle is a China-focused technology investment bill that is making its way through Congress. The United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021, which passed the Senate 68–32 on June 8, stipulates that the United States will “sustain maximum economic pressure” against North Korea until the regime undertakes “complete, verifiable, and irreversible actions toward denuclearization.”8 The bill also calls for universal implementation of existing UN Security Council resolutions against North Korea. If enacted, this provision could seriously disincentivize diplomacy.9

The House companion bill does not include such language on North Korea, setting up a potential face-off between the two chambers. In general, emphasizing coercive measures such as sanctions without factoring in noncoercive diplomatic measures would constrain negotiations and make it more difficult for the United States to properly use its leverage on North Korea.

The second potential legislative vehicle for mandating policy on North Korea is the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which the Senate Armed Services Committee will mark up in July and the House Armed Services Committee will take up in September. One of the only bills to reliably become law, the NDAA has become a go-to vehicle for authorizing new initiatives and shaping U.S. military engagement around the world.

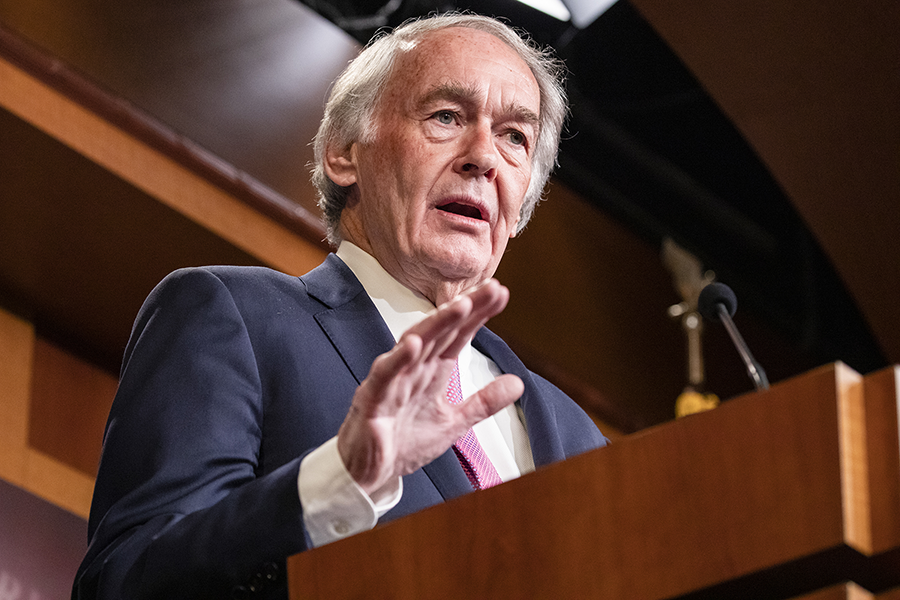

Finally, members of Congress could introduce stand-alone bills to shape U.S. policy. Some measures are quite constructive, such as one introduced by Representative Brad Sherman (D-Calif.), which calls for a formal end to the Korean War and expresses support for establishing U.S. and North Korean liaison offices in their respective capitals.10 A bill introduced by Senator Ed Markey (D-Mass.) and Representative Andy Levin (D-Mich.), titled Enhancing North Korea Humanitarian Assistance Act, aims to ensure that U.S. and UN sanctions imposed on North Korea do not prevent humanitarian aid from reaching those in need.

Finally, members of Congress could introduce stand-alone bills to shape U.S. policy. Some measures are quite constructive, such as one introduced by Representative Brad Sherman (D-Calif.), which calls for a formal end to the Korean War and expresses support for establishing U.S. and North Korean liaison offices in their respective capitals.10 A bill introduced by Senator Ed Markey (D-Mass.) and Representative Andy Levin (D-Mich.), titled Enhancing North Korea Humanitarian Assistance Act, aims to ensure that U.S. and UN sanctions imposed on North Korea do not prevent humanitarian aid from reaching those in need.

Other stand-alone bills are more punitive. For example, the No Social Media Accounts for Terrorists or State Sponsors of Terrorism Act of 2021 would require social media companies such as Twitter and Facebook to delete accounts belonging to senior officials from North Korea and anyone else who is defined in U.S. law as a “specifically designated national.”11 The SAFE Banking Act includes North Korea among the countries whose entities would be hit with greater financial restrictions.

Even if none are enacted, these measures can be used as messaging tools for members of Congress to sway public opinion. The administration needs a Capitol Hill strategy that anticipates and blunts criticisms in advance, including engaging members beyond the traditional national security committees that have long played an outsized, mostly hard-line, role in North Korea-related matters. Members of Congress who belong to the War Powers Caucus, Progressive Caucus, Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus, and other bipartisan affinity groups also represent public preferences on these issues, sometimes with equal or greater intensity than those on national security committees.

Making meaningful progress will be impossible without a willing partner in Pyongyang. The Kim government should engage the administration in good faith, rather than keep it at arm’s length as it has done.12 It should engage in working level talks, even if it prefers the top-down diplomacy of the Trump era. Absent a common understanding on short-term and long-term steps toward reducing tensions and eventually denuclearizing the Korean peninsula, U.S.-North Korean relations will remain stuck. No matter how aligned U.S. policymakers and lawmakers are on policy aims, a coordinated approach by the administration and Congress would send a clear message that the United States wants to engage in serious diplomacy. Biden and his team should reach out to members of Congress early and often, as well as engage outside groups that support more positive U.S.-North Korean relations, with a clear message about what the administration plans to offer and how progress could advance U.S. interests.

One way is by getting North Korea to agree to what Siegfried Hecker, the former Los Alamos weapons laboratory director, called “the three no’s—no more bombs, no better bombs, and no exports—in return for one yes: Washington’s willingness to seriously address North Korea’s fundamental insecurity along the lines of the [2000 U.S.-North Korean] joint communique” which calls for permanently ending the Korean War and affirming that neither government would have “hostile intent” toward the other. The communique also stated both sides’ desire to “remove mistrust, build mutual confidence” including through economic cooperation and exchanges.13

Another possibility is to get North Korea to permanently freeze nuclear and missile tests and to stop transferring proliferation sensitive technologies to other states and non-state groups in return for security guarantees and partial sanctions relief that can snap back if North Korea is noncompliant.

As a U.S. senator for 36 years, Biden understands Congress’ role in shaping foreign policy. He should make building political and public support for his approach to North Korea a top priority. If Congress plays games, Biden should make his case directly to the American people, and not let his North Korea policy become a de facto Obama-era “strategic patience” of maximalist demands and non-engagement.

ENDNOTES

1. “Global Nuclear Arsenals Grow as States Continue to Modernize—New SIPRI Yearbook Out Now,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, June 14, 2021, https://sipri.org/media/press-release/2021/global-nuclear-arsenals-grow-states-continue-modernize-new-sipri-yearbook-out-now

2. David Ignatius, “Biden’s Approach to North Korea Is the Opposite of ‘Fire and Fury,’” The Washington Post, April 15, 2021.

3. “Press Gaggle by Press Secretary Jen Psaki Aboard Air Force One en Route Philadelphia, PA,” White House, April 30, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/press-briefings/2021/04/30/press-gaggle-by-press-secretary-jen-psaki-aboard-air-force-one-en-route-philadelphia-pa/.

4. The White House, “U.S.-ROK Leaders’ Joint Statement,” May 21, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/05/21/u-s-rok-leaders-joint-statement/.

5. Joel Wit, “Opinion: What I Learned Leading America's 1st Nuclear Inspection in North Korea,” NPR, January 22, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/01/22/681174887/opinion-what-i-learned-leading-americas-1st-nuclear-inspection-in-north-korea.

6. 149 Cong. Rec. H4970 (daily ed. June 4, 2003).

7. Joe Wilson, “North Korea: Dialogue With a Bankrupt State,” Official Website of Congressman Joe Wilson, June 15, 2003, https://joewilson.house.gov/media-center/articles/north-korea-dialogue-with-a-bankrupt-state.

8. United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021, S. 1260, 117th Cong., sec. 3234 (2021).

9. Jessica J. Lee, “How the ‘Strategic Competition Act’ Could Actually Stonewall Talks With North Korea,” Responsible Statecraft, May 7, 2021, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2021/05/07/how-the-strategic-competition-act-could-actually-stonewall-talks-with-north-korea/.

10. Peace on the Korean Peninsula Act, H.R. 3446, 117th Cong. (2021).

11. No Social Media Accounts for Terrorists or State Sponsors of Terrorism Act of 2021, H.R. 1543, 117th Cong. (2021).

12. “Exclusive: North Korea Unresponsive to Behind-the-Scenes Biden Administration Outreach—U.S. Official,” Reuters, March 13, 2021.

13. Office of the Spokesman, U.S. Department of State, “U.S.-D.P.R.K. Joint Communique,” October 12, 2000, https://1997-2001.state.gov/regions/eap/001012_usdprk_jointcom.html.

Jessica J. Lee is Senior Research Fellow for East Asia at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and a former congressional staff member.