"No one can solve this problem alone, but together we can change things for the better."

The NPT at 50: Perish or Survive?

March 2020

By Tariq Rauf

On March 5, the three depositaries of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT)—Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—will mark the 50th anniversary of the treaty’s entry into force. The treaty’s 191 states-parties will gather in New York from April 27 to May 22 to hold the treaty’s 10th review conference, which will be presided over by Argentine diplomat Gustavo Zlauvinen. The effectiveness of the treaty for the next 50 years will depend on reconciling two schools of thought on the treaty’s goals: Is it a nonproliferation treaty or a disarmament treaty?

For the five NPT-recognized nuclear-weapon states and the 26 non-nuclear-weapon states that rely on nuclear weapons through extended deterrence arrangements with the United States, the success of the treaty over the past five decades relates to slowing the spread of nuclear weapons to additional states and facilitating cooperation in the peaceful applications of nuclear technology. For this group, the NPT is a nonproliferation treaty.

For the five NPT-recognized nuclear-weapon states and the 26 non-nuclear-weapon states that rely on nuclear weapons through extended deterrence arrangements with the United States, the success of the treaty over the past five decades relates to slowing the spread of nuclear weapons to additional states and facilitating cooperation in the peaceful applications of nuclear technology. For this group, the NPT is a nonproliferation treaty.

A different view is held by 160 of the 186 non-nuclear-weapon states party to the treaty. Their interest is in reducing the number of nuclear weapons, leading eventually to their elimination, and in enjoying the peaceful uses of nuclear energy.

The chasm made by these divergent interests has been deepening, resulting in a loss of civility in NPT forums and in mutual recriminations. Together with the collapsing nuclear arms control architecture, the divide has brought the NPT to an inflection point.

A more significant anniversary will fall on May 11, exactly 25 years after NPT parties agreed without a vote to extend the NPT indefinitely under a framework of strengthening the review process, establishing benchmarks for nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament, and approving a resolution on setting up a zone free of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in the Middle East.1 This framework is under threat.

‘Elephants’ in the NPT Salon

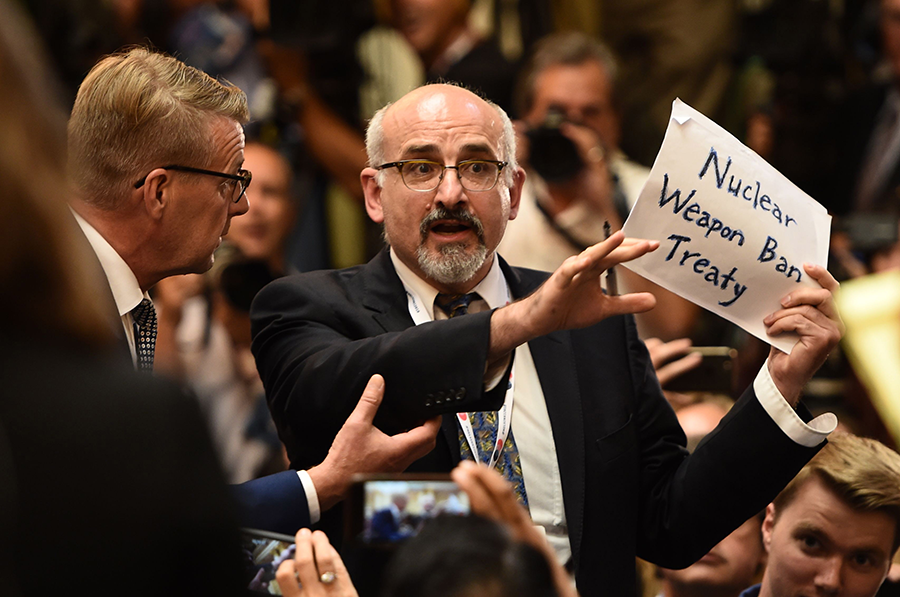

Tension has been steadily building since the failure of states-parties to reach agreement on a final document at the ill-fated 2015 NPT Review Conference.2 A significant number of non-nuclear-weapon states have focused on highlighting the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons use, and they have voted in the UN General Assembly to set up working groups on nuclear disarmament negotiations in 2014 and 2016.3 Despite the strong opposition of the nuclear-weapon states and their followers, this lead, in turn, to the conclusion by 122 states of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which now has 80 signatories and 34 of the 50 ratifications needed for entry into force.4

To counter this brazen challenge to the legitimacy of nuclear weapons and a deterrence-based security system, the United States turned the tables in 2018–2019, in the framework of the NPT preparatory committee sessions, to extend the responsibility for nuclear disarmament from the nuclear-weapon states to all non-nuclear-weapon states as well, by pursuing the initiative titled “Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament” (CEND). Originally, the plan called for creating “conditions,” but U.S. officials replaced that term with “environment” after hearing a chorus of complaints.5 The CEND initiative has swept aside the long-championed traditional step-by-step approach of the Western group, by starting anew from a tabula rasa and abandoning the treaty’s acquis communautaire, the agreed commitments of 1995, 2000, and 2010.6

Yet another bone of contention in the NPT review process concerns the 1995 resolution on the Middle Eastern WMD-free zone that enabled the Arab states and Iran to accept indefinite extension. In 2000, Israel was called out by name to accede to the NPT as a non-nuclear-weapon state. In 2010, following the failure of the 2005 conference partly on the Middle East issue, it was agreed to convene a conference in 2012 on establishing the zone. This conference was not held, and inconclusive multilateral consultations in 2012–2014, attended by nearly all states of the region and Israel, paved the way for the collapse of the 2015 review conference. Regrouping in 2018, the Arab states succeeded in having the UN General Assembly mandate the UN secretary-general to convene a conference on the WMD-free zone that finally was held in New York on November 18-22, 2019,7 and to adopt a political declaration setting up an annual conference process to achieve a Middle Eastern WMD-free zone.8

These are the three “rampaging elephants” in the NPT salon at the review conference. Any discussion of the TPNW pokes the nuclear-weapon-state elephant in the eye, any CEND promotion will rile up the pro-disarmament elephant, and calling on Israel to join negotiations on a Middle Eastern WMD-free zone will enrage the Western group elephant. The nuclear-weapon states and their followers remain adamantly opposed to the TPNW and regard it as undermining the NPT, among other sharp criticisms. Cognizant of such harsh pushback, TPNW supporters and advocates of the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons use are wary of overemphasizing their position while not yielding on their concerns.

Regarding the Middle East, it is an overly optimistic view that the November 2019 conference has defused the issue. Likely, a surprise waiting in the wings could be that the Middle East zone issue now would need to be considered at three levels: UN General Assembly resolutions and the November 2019 conference process; the 1995 resolution; and resolutions on the application of safeguards in the Middle East and on Israeli nuclear capabilities at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).9

Thus, the die is cast for this year’s review conference to degenerate into a Hobbesian fray, perhaps even leading some countries to threaten rhetorically to withdraw from the treaty.

Damn the Review Process?

The deterioration of NPT diplomacy has led more and more non-nuclear-weapon-state parties to question the traditional NPT review process, in which a review conference is held every five years with preparatory committee meetings convening each of the three years before the review conference. The decline of civility in NPT diplomacy, the recurring failure to agree consensually to a factual summary of each session and the recommendations of the preparatory committee, and the inability to review final conference documents periodically have all contributed to non-nuclear-weapon-state frustration. Increasingly, those countries are attacking the integrity and practices of the strengthened review process the treaty parties established in 1995.

Some bizarre notions have been floated, such as holding three annual “decision-making conferences” with one preparatory committee session and a review conference every five years, convening annual general conferences to replace the preparatory committee sessions, addressing an “institutional deficit” by setting up a treaty support unit with up to three dedicated staff officers at the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs,10 establishing an NPT management board,11 and setting up an elected executive council. Fortunately, NPT parties have accepted none of these proposals for diverse reasons.

In 1995, the decision on the “strengthened review process” for the treaty established a substantively revised and efficient structure governing the work of the preparatory committee and the review conference.12 This decision was part of the interlinked, indivisible package of decisions and the resolution that made indefinite extension possible in 1995. Nonetheless, due to the interference and opposition of some of the depositary states, the NPT secretariat was unable to structure the preparatory committee starting in 1997 in accordance with this decision, and most of the non-nuclear-weapon states did not pay sufficient attention. Thus, the 1997-1999 Preparatory Committee sessions were unable to reach any semblance of agreement on recommendations to the review conference. To remedy this situation, while reaffirming the provisions of the 1995 process, the 2000 review conference made adjustments to the strengthened review process that also could not be implemented or put into practice due to inertia and the absence of political will to compromise.

In 1995, the decision on the “strengthened review process” for the treaty established a substantively revised and efficient structure governing the work of the preparatory committee and the review conference.12 This decision was part of the interlinked, indivisible package of decisions and the resolution that made indefinite extension possible in 1995. Nonetheless, due to the interference and opposition of some of the depositary states, the NPT secretariat was unable to structure the preparatory committee starting in 1997 in accordance with this decision, and most of the non-nuclear-weapon states did not pay sufficient attention. Thus, the 1997-1999 Preparatory Committee sessions were unable to reach any semblance of agreement on recommendations to the review conference. To remedy this situation, while reaffirming the provisions of the 1995 process, the 2000 review conference made adjustments to the strengthened review process that also could not be implemented or put into practice due to inertia and the absence of political will to compromise.

To be absolutely clear, the NPT review process itself is neither deficient nor faulty. To paraphrase Shakespeare, the fault is not in the review process but in the states-parties themselves, both with the underlings and the top dogs. Many factors have combined to defeat the purposes of the review process: simple inability and resistance; inflexible group positions; lack of proper preparation; absence of continuity of knowledge and practice; politicization; lengthy, repetitive working papers and statements; reluctance to engage in results-oriented negotiations and interactive discussions; small-group backroom deals; obstinate pressure from the nuclear-weapon states; and disrespect and disregard for agreed outcomes.

Furthermore, as the rules-based order deriving from the precepts of the UN Charter and international law is steadily eroded, the principle of adhering to past agreements is violated, and the acquis of the NPT cast aside. The result is that trust in the NPT and its review process has frayed, thus making it easy to blame the tools of the review process.

The NPT Acquis

Since the failure of the 2015 review conference, some pro-disarmament states have taken to reminding the United States in particular about the acquis, or the accumulated agreed commitments, of the NPT community of states.13 The use of this French term irritates some in the U.S. administration as being sophistry, and in a recent speech in London a senior administration official clearly frustrated by the relentless pressure of the pro-disarmament states referred to them as “dim bulbs” and their attitudes as “some admixture of stupidity and insanity”.14 Never has the level of discourse sunk so low and it does not portend well for developing common ground between nuclear-weapon and non-nuclear-weapon states at the review conference.

Regardless, pursuant to NPT Article VIII.3 and the strengthened review process of 1995 and 2000, the long-standing practice has been to regard agreed review conference commitments as benchmarks or objectives to be implemented to strengthen the authority and integrity of the treaty. Consequently, the actions—the 13 “practical steps” for nuclear disarmament, the principles, and the objectives agreed, respectively, in 2010, 2000, and 1995—serve as guidance and commitments for all states-parties. Dismissing the NPT acquis with a stroke of a pen or by oratorical flourishes can only serve to weaken confidence in the treaty, encourage greater frustration, and deepen differences.

Fin de Régime or a Nouveau Régime?

A quarter-century after indefinite extension of the NPT, it seems to be facing twin crises of relevance and credibility. In the next 25 years, a key question is whether the inflection point is one of fin de régime or a nouveau régime. The question was first posed two decades ago, and states opted in 2000 and 2010 for a nouveau régime, or a “construction for the future.” In 2005 and 2015, however, they opted to “muddle through” when they lost their vision and were unable to agree on the way forward.15 Regrettably, since 2015 it seems that their chosen path is that of a “road to disintegration”16 because of a resumed Cold War, denial of the acquis and past obligations, and willful disregard of established rules.

If so, what might be done to preserve the NPT? At least some of the acquis must be salvaged and the review process buttressed.

The Cold War nuclear arms control architecture is deteriorating rapidly. The trend began in 1999 when the U.S. Senate rejected ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in 1999. Soon after, the United States abandoned the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002. More recently, the United States withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action limiting Iran’s nuclear program in 2018. In more bilateral fashion, the United States and Russia jettisoned the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2019 and appear to be reluctant to sustain the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty and the Open Skies Treaty. Furthermore, they have declined to reaffirm the Reagan-Gorbachev dictum that a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought, and the two rivals appear unable to recognize that any conflict between the United States and Russia could have catastrophic consequences. Such an outcome requires the two sides to prevent any war, whether nuclear or conventional, and to avoid seeking to achieve military superiority. Lastly, their walk away from the agreed NPT commitments of 1995, 2000, and 2010 have contributed to the poisoning of the well of the 2020 review conference.17

The Cold War nuclear arms control architecture is deteriorating rapidly. The trend began in 1999 when the U.S. Senate rejected ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in 1999. Soon after, the United States abandoned the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002. More recently, the United States withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action limiting Iran’s nuclear program in 2018. In more bilateral fashion, the United States and Russia jettisoned the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2019 and appear to be reluctant to sustain the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty and the Open Skies Treaty. Furthermore, they have declined to reaffirm the Reagan-Gorbachev dictum that a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought, and the two rivals appear unable to recognize that any conflict between the United States and Russia could have catastrophic consequences. Such an outcome requires the two sides to prevent any war, whether nuclear or conventional, and to avoid seeking to achieve military superiority. Lastly, their walk away from the agreed NPT commitments of 1995, 2000, and 2010 have contributed to the poisoning of the well of the 2020 review conference.17

On the nuclear disarmament front, there are two diverging paths. The first is to commit to the three existing multilateral treaties: the NPT, CTBT, and TPNW. The NPT is nearly universal; the CTBT is held up in part by four NPT states—China, Egypt, Iran, and the United States—and once the TPNW enters into force, the pro-deterrence states shall face the uncomfortable reality of relying on delegitimized weapons that threaten all of humanity.

The second path is that of the CEND initiative, of chasing rainbows, butterflies, and unicorns toward an illusory environment that will never exist. The nuclear disarmament pillar of the NPT is steadily being hollowed out by lack of implementation of the relevant acquis, and if the treaty is to retain credibility, a course correction is needed. The CEND initiative cannot provide the path to salvation as it is fundamentally flawed and cannot cope with the challenges facing the NPT. There is an inherent disconnect between creation of an environment for nuclear disarmament and the simultaneous rationales for deploying and positing use of low-yield nuclear weapons to somehow strengthen strategic stability or to deescalate a conflict.

With regard to the acquis of the strengthened review process, the prospects again are mixed. On the one hand, a positive development is that the chairs of the three preparatory committee meetings issued state-of-the-NPT reports, when consensus could not be obtained.18 Titled “Reflections of the Chair,” these have reflected continuity in areas of convergence that could be built on at the review conference.19

This innovation should be continued into future review cycles, rather than tinkering with the elements of the 1995 and 2000 review process guidance as discussed above. Another suggested innovation that would heed the 1995 review process guidance is to rationalize the structure and eliminate overlap in main committees but institute an article-by-article review, as is done for all other international treaties.20 This would enable a more efficient, structured, and balanced review.

On the other hand, facing the prospects of stalemate and uncivilized corrosive discourse at the upcoming review conference, some have suggested that the success of review conferences does not necessarily require an agreed final document. The act of holding the conference itself is argued to be sufficient.

Yet, having consecutive review conference failures would be disastrous, and a number of desperate notions are being considered to salvage the conclave. One such idea is to issue a ministerial or high-level declaration on the first or the second day of the conference, affirming the role of the treaty as the cornerstone of the multilateral nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament regime, along with some other elements such as security assurances and universality. The conference can then be concluded as there would be no further incentive to try to negotiate an agreed final document.

Such an outcome would be highly undesirable because it would reflect no confidence in the review process and violate the 1995 requirement of producing a final document in two parts: a backward-looking assessment and review of the treaty’s implementation and the 1995, 2000, and 2010 outcomes during the 2015–2020 time period and recommendations for implementation during the 2020–2025 period.

In reality, multilateral ministerial or high-level declarations generally reflect the lowest common denominator and are toothless. A concise final document along the lines of the 2014 Preparatory Committee chair’s paper,21 not one extending to 100–200 paragraphs, may have better prospects of being negotiated and then adopted by consensus or, alternatively, without objection.

Finally, the time has come to move the NPT review conference from New York to Vienna because it is there that the nonproliferation and peaceful uses of nuclear energy pillars always have been located through the work of the IAEA. A part of the nuclear disarmament pillar now also resides in Vienna in the work of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization. There is no relevant expertise in the New York delegations on any of the three pillars of the NPT, and meetings there are unduly influenced by the vicissitudes of global politics and the perverse shadow of the Security Council, not to mention that conference-related costs are lower in Vienna. Thus, states-parties could seriously consider convening the 2025 and future NPT conferences in Vienna, where the intangible “spirit of Vienna” can work in mysterious ways to foster harmony out of discord.

NPT states have a choice. They can continue trekking along a path to disintegration, or they can collaborate to construct a nouveau régime to preserve the acquis of the world’s most important multilateral nuclear arms control treaty.

The NPT must be preserved and strengthened to provide the essential foundation for eliminating nuclear weapons, preventing further proliferation, and utilizing the peaceful applications of nuclear energy.22 In this regard, the nuclear-weapon states and their followers need to shoulder the greater share of responsibility to build common ground for advancing disarmament, strengthening nonproliferation barriers, and preserving the long-sought and hard-fought achievements of the NPT and its associated regime. With the world now teetering at 100 seconds to midnight on the Doomsday Clock, what other option is there?

ENDNOTES

1. Tariq Rauf and Rebecca Johnson, “After the NPT’s Indefinite Extension: The Future of the Global Nonproliferation Regime,” The Nonproliferation Review, Fall 1995, pp. 28–41.

2. William C. Potter, “The Unfulfilled Promise of the 2015 NPT Review Conference,” Survival, Volume 58, No. 1 (2016): 151-178. For another view, see Tariq Rauf, “The 2015 NPT Review Conference: Setting the Record Straight,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), June 24, 2015, https://www.sipri.org/node/384.

3. See UN Office at Geneva, “Taking Forward Multilateral Nuclear Disarmament Negotiations in 2014,” n.d., https://www.unog.ch/80256EE600585943/(httpPages)/26EE896FB45E01E7C1257BAC00348663?OpenDocument; UN Office at Geneva, “Taking Forward Multilateral Nuclear Disarmament Negotiations in 2016,” n.d., https://www.unog.ch/80256EE600585943/(httpPages)/31F1B64B14E116B2C1257F63003F5453?OpenDocument.

4. Rebecca D. Gibbons, “The Nuclear Ban Treaty: How Did We Get Here, What Does It Mean for the United States?” War on the Rocks, July 14, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/07/the-nuclear-ban-treaty-how-did-we-get-here-what-does-it-mean-for-the-united-states/.

5. Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Creating the Conditions for Nuclear Disarmament (CCND),” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.II/WP.30, April 18, 2018; Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Operationalizing the Creating an Environment for Nuclear Disarmament (CEND) Initiative,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/WP.43, April 26, 2019.

6. Daryl G. Kimball, “Addressing the NPT’s Midlife Crisis,” Arms Control Today, January/February 2020; Tariq Rauf, “CEND Is Creating the Conditions to ‘Never Disarm,’” IDN-InDepthNews, August 5, 2019, https://indepthnews.net/index.php/opinion/2876-cend-is-creating-the-conditions-to-never-disarm-74-years-since-hiroshima-nagasaki.

7. Tariq Rauf, “Achieving the Possible: Weapons of Mass Destruction Free Zone in the Middle East,” IPS Inter Press News Agency, November 20, 2019, http://www.ipsnews.net/2019/11/achieving-possible-weapons-mass-destruction-free-zone-middle-east/.

8. The United States and Israel boycotted the conference, and the United States termed the UN General Assembly’s decision to convene the conference as “illegitimate.” Regarding the conference, see UN General Assembly, “Report of the Conference on the Establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction on the Work of Its First Session,” A/CONF.236/6, November 28, 2019; Tariq Rauf, “Weapons of Mass Destruction Free Middle East,” IPPMediaRoom, November 23, 2019, https://www.ippmedia.com/en/features/weapons-mass-destruction-free-one-middle-east-part-two.

9. UN General Assembly, “Establishment of a Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone in the Region of the Middle East,” A/RES/74/30, December 12, 2019; International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) General Conference, “Application of IAEA Safeguards in the Middle East,” Resolution GC(63)/RES/13, September 2019; IAEA General Conference, “Communication Received From the Resident Representative of Israel Regarding the Request to Include in the Agenda of the Conference an Item Entitled ‘Israeli Nuclear Capabilities,’” GC(63)17, July 30, 2018; IAEA General Conference, “Provisional Agenda,” GC(63)/1/Add.1, July 5, 2019.

10. 2000 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Strengthening the Review Process for the Treaty,” NPT/CONF.2000/WP.4/Rev.1, May 4, 2000; 2010 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Further Strengthening the Review Process of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons,” NPT/CONF.2010/WP.4, March 18, 2010.

11. 2000 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Strengthening the Review Process for the Treaty: Proposal for the Establishment of a Non-Proliferation Treaty Management Board,” NPT/CONF.2000/WP.9, May 9, 2000.

12. 1995 Review and Extension Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Final Document: Part I,” NPT/CONF.1995/32 (Part I), 1995, annex (“Decision 1: Strengthening the Review Process for the Treaty”).

13. For a detailed account and history of the NPT acquis, see Jayantha Dhanapala and Tariq Rauf, eds., “Reflections on the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons: Review Conferences and the Future of the NPT,” SIPRI, April 2017, https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/Reflections%20on%20the%20NPT_Dhanapala%20and%20Rauf.pdf.

14. See, Christopher A. Ford, “The Politics of Arms Control: Getting Beyond Post-Cold War Pathologies and Finding Security in a Competitive Environment”, London, February 11, 2020, https://www.state.gov/the-psychopolitics-of-arms-control/.

15. See Paul Meyer, “The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty: Fin de Regime?” Arms Control Today, April 2017.

16. See Mark Moher, “The Nuclear Disarmament Agenda and the Future of the NPT,” Nonproliferation Review, Fall 1999, pp. 65–69, http://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/npr/moher64.pdf.

17. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum, “Joint Soviet-United States Statement on the Summit Meeting in Geneva,” November 21, 1985, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/research/speeches/112185a.

18. See Tariq Rauf, “Preparing for the 2017 NPT Preparatory Committee Session: The Enhanced Strengthened Review Process,” n.d., https://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/NPT2017_25FEB_RAUF_PrepCom.pdf.

19. Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Towards 2020: Reflections of the Chair of the 2017 Session of the Preparatory Committee,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.I/14, May 15, 2017; Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Chair’s Reflections on the State of the NPT,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.II/12, May 4, 2018; Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, “Reflections of the Chair of the 2019 Session of the Preparatory Committee,” NPT/CONF.2020/PC.III/14, May 13, 2019.

20. See Tom Markram, “Options for the Further Strengthening of the NPT’s Review Process by 2015,” UNODA Occasional Papers, No. 22 (December 2012); Tariq Rauf, “PrepCom Opinion: Farewell to the NPT’s Strengthened Review Process,” Disarmament Diplomacy, No. 26 (May 1998).

21. See Preparatory Committee for the 2015 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, NPT/CONF.2015/PC.III/WP.46, May 8, 2014 (containing “Chairman’s Working Paper: Recommendations by the Chair to the 2015 NPT Review Conference,” prepared for the chair by this author and not adopted due to irreconcilable differences over nuclear disarmament).

22. Tariq Rauf, “Fiftieth Anniversary of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: Preparing for a Successful Outcome,” Asia Pacific Leadership Network and Centre for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Policy Brief, No. 48 (November 2017), http://www.isodarco.com/courses/andalo19/paper/iso19_Rauf.pdf.

Tariq Rauf has attended all nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) meetings since 1987 as a delegate, including as senior adviser to the chair of Main Committee I (nuclear disarmament) in 2015 and to the chair of the 2014 preparatory committee; as alternate head of the International Atomic Energy Agency delegation to the NPT; and as a nonproliferation expert with the Canadian delegation from 1987 to 2000.