“For half a century, ACA has been providing the world … with advocacy, analysis, and awareness on some of the most critical topics of international peace and security, including on how to achieve our common, shared goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.”

The Demise of the ABM Treaty: An Insider Recounts the Final Days

November 2019

By Edward Ifft

Arms control is going through a very difficult period. The 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty is gone, the 1990 Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty is basically dead, the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran is in tatters, the future of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) is in doubt, it appears possible the United States will withdraw from the 1992 Open Skies Treaty, and there are concerns over whether damage will be done to the 1968 nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty at its review conference next year.

It is useful to consider the events surrounding what seems to have started this unhealthy trend: the U.S. withdrawal from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 2002. This was the first major defection from a modern arms control agreement.

It is useful to consider the events surrounding what seems to have started this unhealthy trend: the U.S. withdrawal from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 2002. This was the first major defection from a modern arms control agreement.

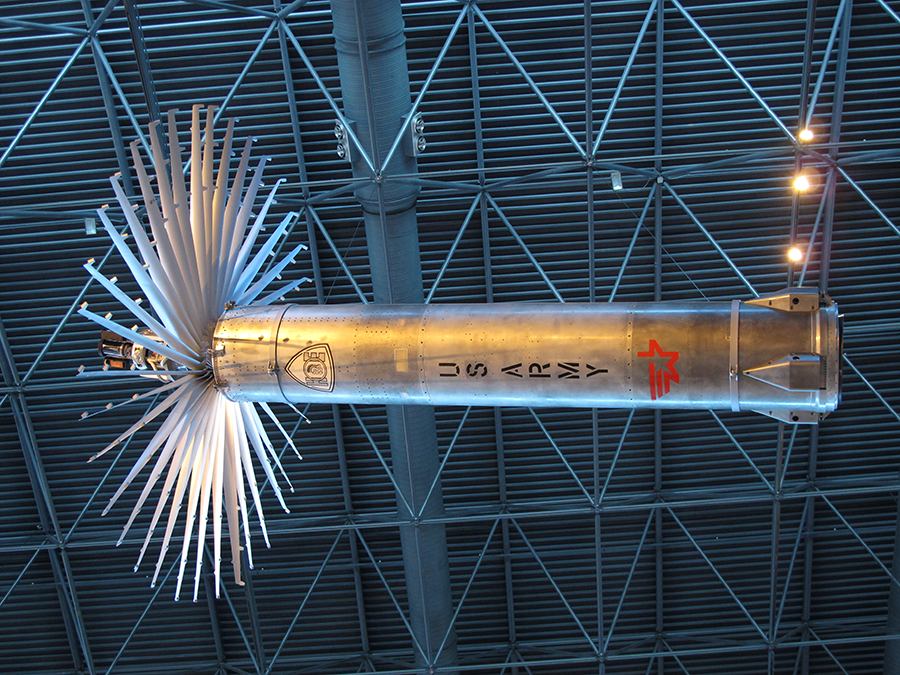

The ABM Treaty, which strictly constrained the ballistic missile defense systems of the U.S. and Soviet Union, was negotiated as part of the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) process, was approved by the Senate in an 88-2 vote, and entered into force in 1972. Further constraints were imposed in a 1974 protocol. Although a relatively small but influential group of U.S. advocates never reconciled to the idea that the United States would remain vulnerable to a large ballistic missile attack, most attention during the next decade was focused on constraining offensive forces.

President Ronald Reagan’s 1983 speech advocating a large ballistic missile defense system to protect the entire country changed that. Although the Strategic Defense Initiative, also known as “Star Wars,” proved to be neither wise nor feasible, its goal was never actually renounced by U.S. leaders. Against this background, the Defense and Space Negotiating Group labored throughout the late 1980s to persuade the Soviet Union to loosen or reinterpret the ABM Treaty. It grappled with the concepts of research, development, and testing and what was allowed under the treaty. It failed in this effort, leaving hard feelings on both sides. The other two components of the Nuclear and Space Talks in Geneva successfully negotiated the INF Treaty and the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START).

Against this contentious background, the treaty’s Standing Consultative Commission (SCC), which was formed to implement the ABM Treaty, became the forum for U.S.-Soviet discussions. It had taken on the difficult task of trying to formulate technical criteria that could separate air defense interceptors from ballistic missile defense interceptors. It seemed obvious that this would be desirable in order to establish a clear boundary between legal and illegal activities, but the very idea was opposed by some in the Bush administration and Congress. Although U.S. and Soviet officials did manage to formulate some such technical criteria in the SCC, they were not accepted in Washington.

Stanley Riveles retired as U.S. SCC commissioner, and I was appointed acting commissioner in the summer of 2000. About the only enjoyable part of this assignment was a trip in August 2000 to the U.S. base in Thule, Greenland, for consultations with Denmark on upgrading the U.S. early-warning radars based there. A routine SCC session was held in the fall of 2000, and the fateful final session was scheduled for November-December 2001. The administration insisted that the session be limited to two weeks, not nearly enough time to deal properly with the complicated issues in play, but higher official levels may have already decided on the outcome.

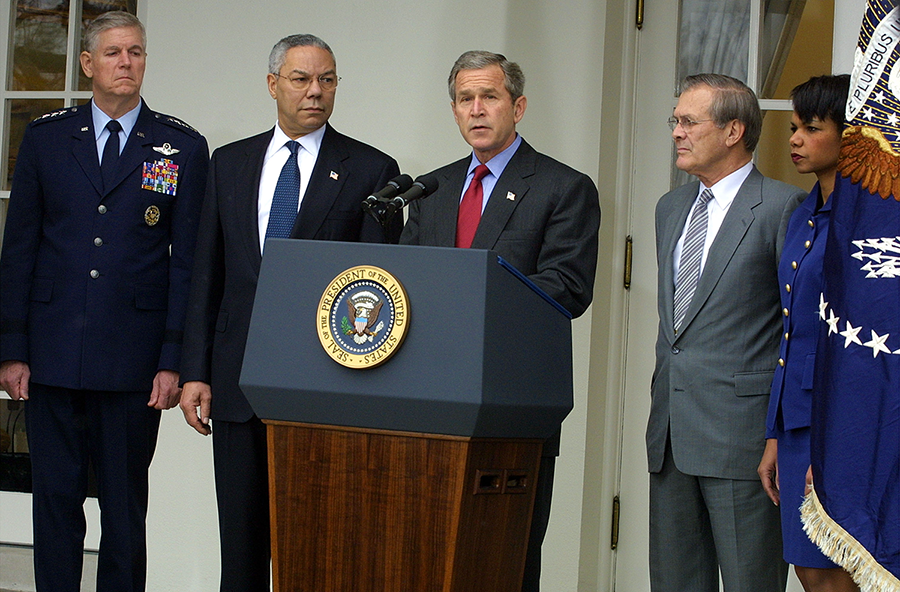

Strongly influenced by the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the United States, as well as the perceived future ballistic missile threat from Iran and North Korea, President George W. Bush’s administration sought to loosen or eliminate the ABM Treaty to gain greater freedom to conduct testing of more exotic ballistic missile defense systems and deploy limited defenses against accidental or unauthorized attacks, and those by what they called rogue states. The former Soviet states sought to block all this by preserving the ABM Treaty as written and interpreted. The administration had put forward the idea that the United States and Russia should withdraw from the treaty together. There was about as much chance of that as of the United States acquiring Greenland today. The rest of the world strongly supported the treaty, which had repeatedly been called “the cornerstone of international security.” One of the “13 practical steps” unanimously agreed at the 2000 NPT Review Conference called for “the preservation and strengthening” of the ABM Treaty.

The question of who should be at the table in the SCC was somewhat awkward. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, 15 independent countries instantly appeared, and the question arose of what to do about the international arms control obligations the Soviet Union had undertaken. International law on this subject had not been tested often. The successor states to START were the four that inherited nuclear weapons on their territory and would accept inspections: Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine. Successor states for the INF Treaty included all 15 former Soviet states, except for the three Baltic states, which had a special status. The CFE Treaty had eight successor states, and so on. It appeared obvious that the four START states would be successors for the ABM Treaty, and they showed up at the SCC. Some in the Bush administration claimed that only the Russian Federation should be there because all legal ballistic missile defense systems were deployed in Russia. In addition, it would be easier to get rid of a treaty with only one other party rather than four. The U.S. SCC delegation had no clear instructions on the matter, but were certainly aware of the controversy in Washington. Ukraine in particular felt strongly about this and told me the United States had no right to pick and choose for which treaties Ukraine would be allowed to be a successor state. There was also the inconvenient fact that the United States had taken the strong early position that the former Soviet republics must accept all the arms control obligations of the Soviet Union. The Ukrainian commissioner put me on the spot in a plenary meeting by asking how I viewed Ukrainian participation. Avoiding the legal issue, I replied that I viewed him as a “valued participant.” That seemed to put the issue to rest. In any case, there were always four countries on the other side of the table; we treated them as equals, and they hosted meetings and participated fully. The new countries naturally found themselves with a shortage of diplomats to behave as sovereign countries. The Kazakhstani commissioner was actually a gynecologist, but made a good diplomat and represented his country well. The Russian commissioner was Colonel Viktor Koltunov, a respected arms control expert and friend from the START negotiations.

The question of who should be at the table in the SCC was somewhat awkward. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, 15 independent countries instantly appeared, and the question arose of what to do about the international arms control obligations the Soviet Union had undertaken. International law on this subject had not been tested often. The successor states to START were the four that inherited nuclear weapons on their territory and would accept inspections: Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine. Successor states for the INF Treaty included all 15 former Soviet states, except for the three Baltic states, which had a special status. The CFE Treaty had eight successor states, and so on. It appeared obvious that the four START states would be successors for the ABM Treaty, and they showed up at the SCC. Some in the Bush administration claimed that only the Russian Federation should be there because all legal ballistic missile defense systems were deployed in Russia. In addition, it would be easier to get rid of a treaty with only one other party rather than four. The U.S. SCC delegation had no clear instructions on the matter, but were certainly aware of the controversy in Washington. Ukraine in particular felt strongly about this and told me the United States had no right to pick and choose for which treaties Ukraine would be allowed to be a successor state. There was also the inconvenient fact that the United States had taken the strong early position that the former Soviet republics must accept all the arms control obligations of the Soviet Union. The Ukrainian commissioner put me on the spot in a plenary meeting by asking how I viewed Ukrainian participation. Avoiding the legal issue, I replied that I viewed him as a “valued participant.” That seemed to put the issue to rest. In any case, there were always four countries on the other side of the table; we treated them as equals, and they hosted meetings and participated fully. The new countries naturally found themselves with a shortage of diplomats to behave as sovereign countries. The Kazakhstani commissioner was actually a gynecologist, but made a good diplomat and represented his country well. The Russian commissioner was Colonel Viktor Koltunov, a respected arms control expert and friend from the START negotiations.

Working Hard in Geneva

The first SCC session began November 3, 2001, with meetings of commissioners only at the U.S. mission in Geneva. The next day, the opening plenary was held at the Russian mission and went well. On Wednesday, I hosted Koltunov for lunch at Roberto’s, probably the best Italian restaurant in Switzerland. The conversation was pleasant but without any noticeable progress. On the way back to the U.S. mission, I expressed my disappointment to my interpreter. He replied, “Russians don’t really get the concept of pasta.” This gave me the feeling that I had been not only unable to produce any substantive progress, but had bungled the menu as well. On November 6, I took the Ukrainian commissioner to lunch, where he showed a good understanding of U.S. concerns but could offer no solutions. He seemed comfortable with my made-up concept of valued participant.

During the next day’s plenary meeting hosted by Ukraine, we enlisted the help of the Cumaen Sybil. In Roman mythology, the Cumaen Sybil was a mysterious prophetess who offered King Tarquin nine books of prophecy but at a high price. The king refused, and the sybil burned three of the books and repeated the offer. He again refused, and the sequence was repeated. The king finally ended up buying three books for a price that could have brought him all nine. The analogy was clear: time for saving the treaty was running out, and the United States was not going to lower the price for preserving it.

The other side of the table was not impressed. I had hoped it at least might awaken memories on the Russian side of how Soviet ambassador Vladimir Semenov, a gentleman of high culture, often referred to classical mythology during the original SALT. The most memorable of these was his reference to the “Procrustean bed.” This sent the U.S. delegation in Vienna, in the days before Google, scrambling to figure out what he was talking about.

Endgame

According to some reports, by this time, Bush had already called Russian President Vladimir Putin to inform him of the U.S. intent to withdraw from the treaty. If so, our hard work was irrelevant and in line with a long tradition of keeping U.S. delegations in the field in the dark about what is happening at higher levels.

On December 10, we gave an important presentation on the U.S. view of the ballistic missile threat from Iran. This received polite interest from the other side but little more. There were no meetings the next day, but we held a very pleasant reception for the other delegations at the government’s apartment overlooking Lake Geneva. Although the delegation sent in prompt and comprehensive written reports to Washington, I was required to make regular secure phone calls from the U.S. mission to the National Security Council staff to report on developments. During the December 11 evening call, my contact informed me that he would be out of town the next day. I expressed the hope there would be no surprises while he was gone. After a pregnant pause, he said, “Not tomorrow.” This was certainly ominous but hardly actionable. The following day, I was instructed to call that evening for an urgent message. After dinner in France with some delegation members, I stopped by the mission and called around midnight and was informed that the United States would give formal notice of its intention to withdraw in all four capitals the next morning.

That day, December 13, saw all the delegations assembled at the Russian mission for a planned plenary. Russia, as the host, was scheduled to speak before the United States; but while entering the meeting hall, I asked Koltunov to speak first so I could make an important statement. He granted the request, and I made a brief formal diplomatic statement announcing what had happened about two hours earlier in the four capitals.

This clearly shocked everyone on the other side of the table. Koltunov called a timeout to consult with his colleagues. After a few minutes, he returned and announced there was no point in having the four countries deliver their planned statements. As luck would have it, the Russians had planned for a reception following the plenary, in part in response to the U.S. reception two days earlier. Mercifully, the doors opened, and there was spread out in the next room a typically generous Russian buffet.

This was a rather awkward event. Koltunov at first avoided me, and I chatted with other Russians, who were principally interested in when I had heard the news. The U.S. reception had been moved up a couple of days, so it happened before the withdrawal notice. This could have appeared to the Russians as some rather sneaky choreography, which it was not. Eventually, Koltunov came over to chat. Searching for a way to smooth things over and minimize the damage to U.S.-Russian relations, I remarked that when we held our 10-year reunion, we would wonder why people had thought this was such a big deal. He instantly responded that we would wonder “how people could have been so stupid.” Of course, there was no 10-year reunion, and history can judge which of these two predictions was closer to the mark.

I have met Koltunov, (now I believe a retired General) several times at conferences in Moscow, where he is associated with a leading think tank. We are still friends and understand each of us was doing his best to represent his country. The final plenary was a brief and rather sad affair at the U.S. Mission the next day.

Consequences

The formal U.S. withdrawal from the treaty took effect six months after these events, on June 13, 2002. Putin’s response was surprisingly restrained. He called it a “mistake” but one that did not damage Russia’s security. For his part, Bush was conciliatory, expressing his hopes for continued cooperation.

In retrospect, all the SCC hard work and drama was probably a sideshow, with no chance of success and little impact on capitals. On the other hand, having a forum where the five countries could hold in-depth confidential talks on this difficult subject, along with developing some measure of personal trust and understanding, was surely of some value. One might even speculate that the relatively restrained aftermath was influenced by that work.

No delegation showed a willingness to compromise on the ballistic missile defense question. Russia showed no flexibility whatsoever in all SCC discussions. The United States, in addition to being vague on how the treaty could be preserved, had sent out signals that even if Russia met its demands for loosening the treaty, more demands would be forthcoming later.

Seventeen years after these events, the United States has undertaken fewer ballistic missile defense tests and deployments than would have been expected. The changes to the treaty needed to legalize what has happened so far would certainly have been substantive but not monumental. One wonders whether Moscow has ever had second thoughts about its hard-line stance in 2001.

U.S.-Russian relations, of which arms control is a crucial component, have been spiraling downward in a way in which everyone loses. Russia itself bears much of the blame for this, especially for its actions in Georgia and Ukraine, along with attacks on Western electoral processes and its actions with respect to the INF Treaty. This has all been well documented and analyzed. Less well understood is the Russian perception that it is the West, principally the United States, that broke the agreements and understandings that formed the foundations for a new world order built up by Presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Boris Yeltsin. This list includes NATO expansion, the war in Iraq, the bombing and dismemberment of Serbia, the destruction of Libya, the disdain of the George W. Bush administration toward Russia, perceived involvement in the Color Revolutions in the near abroad and in unrest in Russia itself, and so on. In the view of many in Moscow, this all began with the shock of U.S. withdrawal from the ABM Treaty.

U.S.-Russian relations, of which arms control is a crucial component, have been spiraling downward in a way in which everyone loses. Russia itself bears much of the blame for this, especially for its actions in Georgia and Ukraine, along with attacks on Western electoral processes and its actions with respect to the INF Treaty. This has all been well documented and analyzed. Less well understood is the Russian perception that it is the West, principally the United States, that broke the agreements and understandings that formed the foundations for a new world order built up by Presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Boris Yeltsin. This list includes NATO expansion, the war in Iraq, the bombing and dismemberment of Serbia, the destruction of Libya, the disdain of the George W. Bush administration toward Russia, perceived involvement in the Color Revolutions in the near abroad and in unrest in Russia itself, and so on. In the view of many in Moscow, this all began with the shock of U.S. withdrawal from the ABM Treaty.

In the military sphere, Russia’s massive expansion of its capabilities is partly a normal catching up from its decade of troubles following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, along with the normal replacement of aging systems. Yet, Russia has been quite open in saying that some of this, especially new, more exotic systems, is a response to unconstrained U.S. ballistic missile defense programs. Although the relatively restrained U.S. programs to date would hardly justify this, the fact that the United States refuses to provide any assurances about future programs or to even consider constraints on kill mechanisms in orbit, allows worst-case scenarios to run wild in Moscow (and Beijing). The preamble to New START sensibly addresses the relationship between current and future offensive and defensive systems, but this has not led to any useful negotiations on how to deal with this relationship.

People of goodwill, including Russian leaders right up to Putin in his early period as president, welcomed the “new world order,” “Europe whole and free,” “Europe to the Urals,” “Vancouver to Vladivostok,” and so on. Fulfillment of all these brave slogans was strongly dependent on cooperative and respectful if not friendly relationships between Russia and the West. Neither side has worked hard enough to make this happen, and one could make a strong case that the ABM Treaty saga was the point at which things began to fall apart.

In June 2002, U.S. State Department official David Nickels and I returned to Geneva for a week to close out the SCC. We went through voluminous files, organized them, boxed them up, and shipped them to the State Department archives in accordance with regulations. There is an understanding that SCC records will not be made public without the permission of both sides, but they remain there to this day, awaiting the attention of some future historian, who could seek declassification and access under the Freedom of Information Act.

Edward Ifft participated in negotiating and implementing many key arms control agreements of the past 45 years at the U.S. State Department, and at details to the Defense Department and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. He served as the last U.S. commissioner for the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty until the U.S. withdrawal from the treaty in 2002.