U.S. Nuclear Warhead Costs Still Rising

September 2019

By Kingston Reif

The estimated cost of sustaining U.S. nuclear warheads and their supporting infrastructure continues to rise, according to the Energy Department’s latest annual report on the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan. Prepared by the department’s semi-autonomous National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the July report illustrates the rising cost of the government’s nuclear mission as the Trump administration implements the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, which calls for expanding U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities. (See ACT, March 2018.)

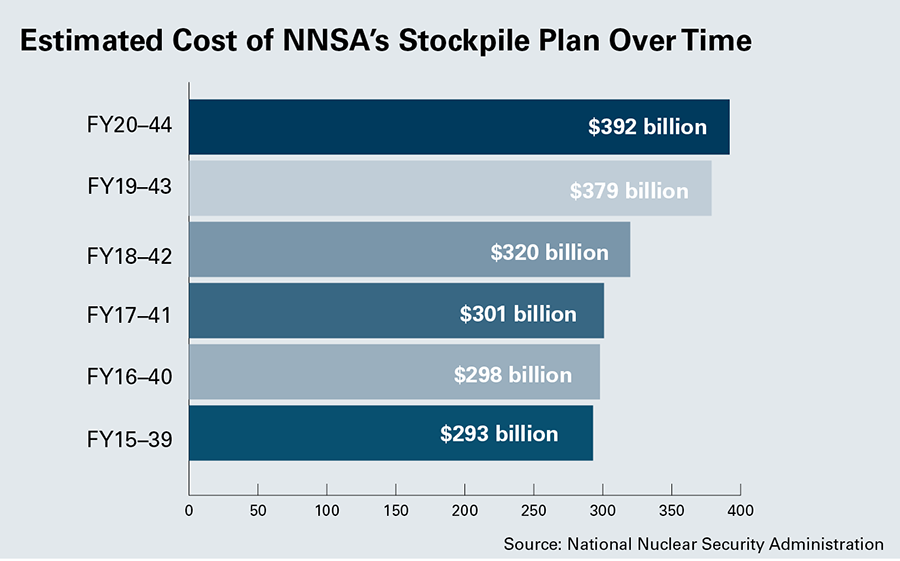

The fiscal year 2020 iteration projects more than $392 billion in spending, after inflation, on agency efforts related to sustaining and modernizing the nuclear weapons stockpile over the next 25 years. This is an increase of $13 billion from the 2019 version of the plan. (See ACT, December 2018.)

The fiscal year 2020 iteration projects more than $392 billion in spending, after inflation, on agency efforts related to sustaining and modernizing the nuclear weapons stockpile over the next 25 years. This is an increase of $13 billion from the 2019 version of the plan. (See ACT, December 2018.)

The NNSA states that the projected growth in spending is “affordable and executable,” but the projected cost of the plan falls at the low end of an estimated range of $386 billion to $423 billion. The agency has historically struggled to complete large infrastructure and facility recapitalization projects on time and on budget.

Overall, the Trump administration is requesting $37.3 billion in fiscal year 2020 for the Defense and Energy departments to sustain and modernize U.S. nuclear delivery systems and warheads and their supporting infrastructure, an increase of about $2 billion from the fiscal year 2019 appropriation. (See ACT, April 2019.)

Of that amount, the NNSA is requesting $12.4 billion for its weapons program, an increase of $1.3 billion from the fiscal year 2019 appropriation and $530 million from the projection for fiscal year 2020 in the fiscal year 2019 budget request.

A major source of projected growth in the new stockpile plan is in the area of nuclear warhead life-extension programs. The total cumulative costs over 25 years for these programs increased by approximately $4 billion from the 2019 estimate.

The plan attributes the higher projected costs to “2018 Nuclear Posture Review implementation, refined requirements that increase scope complexity, accelerated production schedule milestones, updated assumptions for future warheads, and the escalation costs of a future year replacing a lower-cost early year.”

The estimated cost under the plan to upgrade the warhead for the existing air-launched cruise missile rose to $11.2 billion, an increase of $1.2 billion from the estimated cost as of last year’s plan.

The estimated cost of the B61 life extension program held steady at $7.6 billion, but the department reported that the program “is experiencing an unresolved technical issue related to the qualification of electrical components used in non-nuclear assemblies,” which is expected to delay the previously planned first production-unit date of March 2020. (See ACT, June 2019.) The plan states that additional “testing is required to ascertain the impacts and whether a change in initial operational capability dates are necessary.”

The NNSA Office of Cost Estimating and Program Evaluation projected in 2017 a total program cost of approximately $10 billion and a two-year delay to the agency’s first production-unit date. (See ACT, June 2017.)

The stockpile plan notes that the NNSA’s goal remains to produce at least 80 plutonium pits per year as directed in the Nuclear Posture Review. (See ACT, June 2018.)

That goal may be difficult to reach. The Institute for Defense Analyses, a federally funded research organization, reported in April that the agency’s 80-pit goal by 2030 cannot be met. The institute’s study found “no historical precedent to support” achieving such a capability by 2030.

In addition, the stockpile plan reveals that the NNSA and Pentagon have established a “Deeply Buried Target Defeat Team…to determine future options for defeating such targets.” This suggests the administration could consider the development of a new earth-penetrating nuclear weapon. (See ACT, December 2005.)