The 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) between the United States and Russia is set to expire in February 2021. Although the two nations could extend the treaty by up to five years (and there is bipartisan congressional support for such a step), the future of New START remains uncertain, in part because the Trump administration wants to include China in any future arms control deal.

Integrating China further into international nuclear arms control efforts is a worthy goal, but extending New START should not hinge on China’s participation. Given China’s relatively minimalist nuclear posture and its low state of nuclear readiness, Beijing is unlikely to participate in a trilateral arms reduction agreement. It would be a mistake to lose the benefits of New START while waiting for an implausible trilateral treaty.

Integrating China further into international nuclear arms control efforts is a worthy goal, but extending New START should not hinge on China’s participation. Given China’s relatively minimalist nuclear posture and its low state of nuclear readiness, Beijing is unlikely to participate in a trilateral arms reduction agreement. It would be a mistake to lose the benefits of New START while waiting for an implausible trilateral treaty.

New START caps the deployed U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals at 1,550 warheads, 700 missiles and heavy bombers, and 800 missile launchers and bombers. In the wake of the collapse of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty Aug. 2, New START is now the only remaining agreement constraining the size of the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals.

John Bolton, Trump’s national security adviser, stated in a May 2019 interview that while no final decision has been, a New START extension is unlikely. Among Bolton’s criticisms of New START is that it does not address China’s nuclear capabilities.

“Cold War-style, bilateral strategic arms negotiations don’t make sense when you’re in a multipolar nuclear world,” he said. China “remain[s] outside an arms control framework and can build up to an unlimited level.”

Bolton’s insistence on including China in a future strategic arms reduction treaty is now reflected in Trump’s stance. The White House is seeking a more comprehensive arms control deal that includes Russia and China and limits nuclear weapons not covered by New START, such as Russia’s large arsenal of shorter-range “tactical” nuclear weapons.

Asked May 3 about adding China to a trilateral treaty, Trump said that he had “already spoken with [China]; they very much would like to be a part of that deal.” However, in a July 16 press release conference, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang made clear that China will not participate in a “so-called China-U.S.-Russia trilateral disarmament negotiation.”

China’s decision to not participate is in keeping with its 2010 White Paper on National Security. The document puts the onus for nuclear disarmament squarely on the shoulders of Russia and the United States, stating that the countries possessing the largest nuclear arsenals bear special and primary responsibility for nuclear disarmament. The Chinese White Paper argues that once those countries have taken verifiable, legally binding, and irreversible steps to drastically reduce their nuclear arsenals will there be the necessary conditions for other nuclear-weapon states to join in on multilateral negotiations on nuclear disarmament.

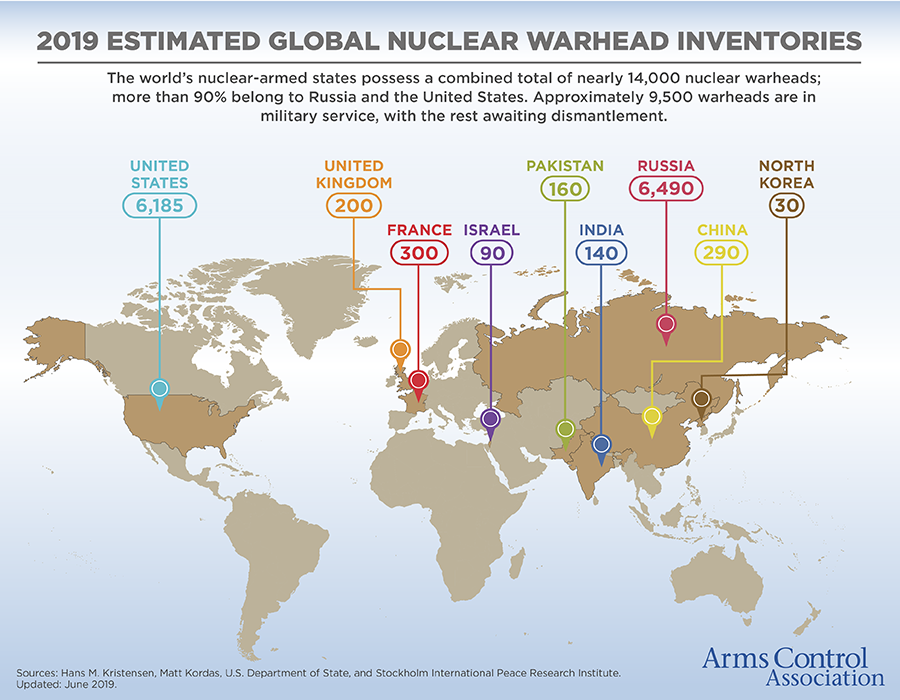

China has a relatively small nuclear arsenal compared to the United States and Russia. China has around 290 warheads, while Russia and the United States and Russia are estimated to have approximately 6,490 and 6,185 nuclear warheads, respectively.

The focus on warhead numbers alone, however, misses the other important aspects of China’s nuclear posture with implications for arms control negotiations.

China is believed to keep warheads de-mated from delivery systems. This is a reflection of China’s consistent "no-first-use" position and its policy of “keep[ing] its nuclear capabilities at the minimum level required for national security.” There have been no official reports indicating that the policy of keeping warheads and missiles de-mated has changed.

If these weapons were counted using New START rules, which hold accountable only warheads deployed on long-range missiles, bombers, and submarines, China would be considered to have zero warheads deployed on long-range missiles. Under New START counting rules, one nuclear warhead is counted for each deployed heavy bomber. China is thought to have one known nuclear-capable aircraft, the H-6K (B-6 NATO designation). The fleet includes 20 bombers. Regardless of whether or not these dual-capable bombers are carrying a nuclear warhead, they would be counted as one warhead, giving China a total of 20 deployed warheads under New START counting rules.

In contrast, the treaty limits the United States and Russia to no more than 1,550 deployed strategic warheads each, and as of the last treaty data exchange, the United States reported 1,365 deployed warheads while Russia reported 1,461 deployed warheads.

This begs the question of what the administration’s goal is in seeking to include China in arms control talks. In a July 2019 testimony in front of a House Committee on Foreign Affairs subcommittee, Arms Control Association Board Chairman Thomas Countryman said that committing China to New START limitations would either mean “giving our blessing to a fivefold increase in China’s weapon stockpile” or “agree[ing] to reduce American and Russian deployments to the level of China.”

In a recent interview with the Arms Control Association, Li Bin, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a professor at Tsinghua University, said that if the new trilateral strategic arms reduction treaty were to include a newly defined counting system that reflected total arsenal size rather than deployed arsenal size, China should consider participating. He contends that such a treaty would demonstrate the high level of commitment to disarmament that China expects from Russia and the United States.

Gregory Kulacki, a senior analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists, argued in a recent article that by quietly turning down the Trump administration’s proposal to engage in arms control talks, China forfeited the opportunity to become a leader in arms control and educate an international audience on its “comparatively reserved nuclear policies.”

Arms Control Association executive director Daryl Kimball has suggested that one realistic approach to engaging China in the nuclear risk reduction process would be for the United States and Russia to extend New START, which “could help put pressure on China to provide more information about its nuclear weapons and fissile material stockpiles.” In that case, it would also be reasonable to ask China to freeze the overall size of its nuclear arsenal, so long as the United States and Russia continue to make progress to reduce their far larger arsenals.

News outlets have been quick to label China as completely averse to arms control, but this is not the full story. In 2008, for example, China led a group of experts from the five nuclear-armed countries to produce a Glossary of Key Nuclear Terms. As Li Bin has written, important security concepts are not easily translated between languages. The creation of the glossary demonstrated China’s interest in enhancing its ability to participate in international arms control efforts.

China participated in the negotiations that led to the conclusion of the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) and it has signed the treaty. However, Beijing has dragged its feet on ratifying the agreement despite official support for entry into force.

The Trump administration must also grapple with what it would take to bring China to the negotiating table for any future arms control agreement. For example, a major point of contention for Russia, China, and the United States is missile defense. As retired Lt. Gen. Frank Klotz pointed out recently, missile defense will “be part of, I think, a Russian ask, a Chinese ask for any substantive change to the basic outlines of—and central limits of—a New START Treaty or a successor to a New START treaty.”

In its 2010 National Defense White Paper, China specifically cited global missile defense programs as being detrimental to international strategic stability and having a negative impact on the process of nuclear disarmament. It added that “no state should deploy overseas missile defense systems that have strategic missile defense capabilities or potential, or engage in any such international collaboration.”

In his July 2019 testimony, Countryman stated that while “[p]ursuing talks with other nuclear-armed states and trying to limit all types of nuclear weapons is a noble objective ... there is no realistic chance that such an agreement could be reached ... before New START expires. That leads to the conclusion that this is a deliberate ‘poison pill’—a pretext to running out the clock in order to kill New START.”

There is no doubt that including all nuclear-weapon states in the arms control and nuclear disarmament conversation is a necessary longer-term objective. However, before this can occur, the administration must dedicate time and effort into crafting proposals longer than one-sentence sound bites. It must also extend New START to provide a stable foundation on which to pursue further efforts.