"[Arms Control Today] has become indispensable! I think it is the combination of the critical period we are in and the quality of the product. I found myself reading the May issue from cover to cover."

July/August 2020

Arms Control Today July/August 2020

Edition Date

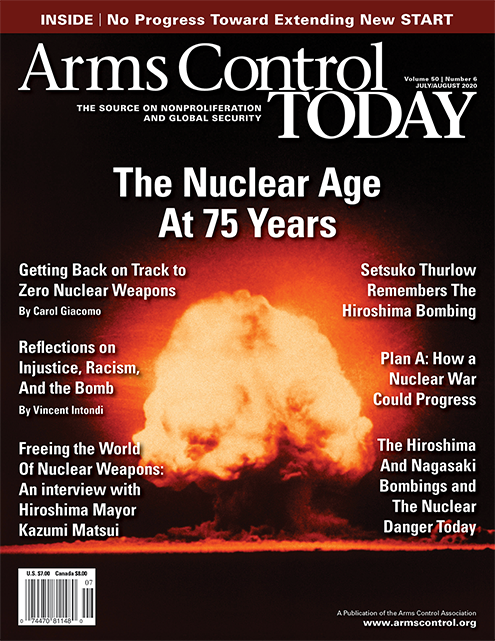

Cover Image

Authored by on July 1, 2020

Authored by on July 1, 2020

Authored by on July 1, 2020

Authored by on July 1, 2020

Authored by on July 1, 2020

Authored by on July 1, 2020

Authored by on July 1, 2020

Authored by on July 1, 2020

Authored by on July 1, 2020

Authored by on July 1, 2020