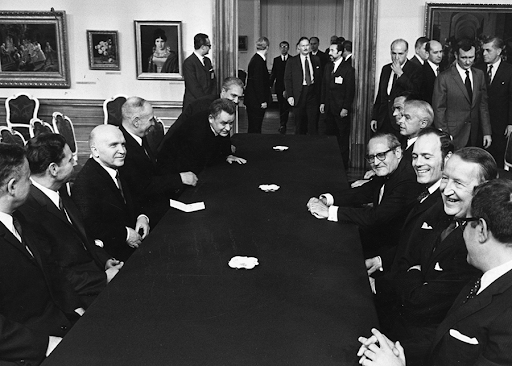

Fifty years ago, on May 26, 1972, the first bilateral nuclear arms control agreements were struck: the U.S.-Soviet Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. The breakthrough agreements, which began the process of slowing the nuclear arms race, followed the entry into force of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty in 1970. The U.S.-Soviet agreements were the product of intensive negotiations that began in 1969. The chief American negotiator was Gerard Smith, who had been appointed the director of the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency by then-president Richard Nixon.

Smith’s opening message that day: “The limitation of strategic arms is in the mutual interests of our country and the Soviet Union.”

Negotiated in the midst of severe tensions, the SALT agreement and the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty were the first restrictions on the superpowers’ massive strategic offensive weapons, as well as on their emerging strategic defensive systems. The SALT agreement and the ABM Treaty helped establish greater confidence and predictability and opened a period of U.S.-Soviet detente that lessened the threat of nuclear war.

Negotiated in the midst of severe tensions, the SALT agreement and the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty were the first restrictions on the superpowers’ massive strategic offensive weapons, as well as on their emerging strategic defensive systems. The SALT agreement and the ABM Treaty helped establish greater confidence and predictability and opened a period of U.S.-Soviet detente that lessened the threat of nuclear war.

SALT was an executive agreement that capped U.S. and Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) and submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) forces. Under SALT, both sides pledged not to construct new ICBM silos, not to increase the size of existing ICBM silos “significantly,” and capped the number of SLBM launch tubes and SLBM-carrying submarines. The agreement limited the United States to 1,054 ICBM silos and 656 SLBM launch tubes. The Soviet Union was limited to 1,607 ICBM silos and 740 SLBM launch tubes. Unfortunately, the agreement did not restrict strategic bombers and did not cap warhead numbers, leaving both sides free to enlarge their forces by increasing their bomber-based forces and by exploiting a newly developed technology, the deployment of multiple warheads (MIRVs) on their ICBMs and SLBMs.

The Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty limited strategic missile defenses to 200 interceptors (later 100) each and prevented the emergence of a destabilizing offense-defense arms race. In June 2002, the United States unilaterally withdrew from the ABM Treaty over Russian objections and warnings from independent experts about the adverse effects on strategic stability and further efforts to reduce offensive nuclear stockpiles in the future.

Though imperfect, the agreements that resulted from the SALT negotiations were a modest first step toward meeting U.S. and Russian obligations under Article VI of the 1968 Nuclear Nonproliferation Treat (NPT) to pursue effective measures to end the arms race and achieve nuclear disarmament. The SALT and ABM agreements also set a standard for future bilateral nuclear arms control treaty negotiations that would lead to more ambitious verifiable limitations and reductions of two sides' excessive nuclear stockpiles.

After the ABM Treaty and SALT agreement were concluded in 1972, Smith left the government but continued his work to prevent a nuclear catastrophe in part by joining the Board of Directors of the newly-formed Arms Control Association. He served as the Association’s chairman from 1981 to 1992.

Since the SALT and ABM agreements were concluded, every U.S. president except for Donald J. Trump, has successfully concluded at least one agreement with the Soviet Union, or later Russia, to reduce the dangers posed by nuclear weapons to the United States and the world.

These bilateral nuclear arms control agreements have not ended the arms race and the risk of nuclear conflict, but they have estalished an essential foundation for avoiding escalation and negotiations on further reductions in the their still deadly nuclear arsenals, as required under Article VI of the NPT.

But the only remaining U.S.-Russian arms reduction agreement, the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, expires in 2026.

But the only remaining U.S.-Russian arms reduction agreement, the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, expires in 2026.

In late 2021, a U.S.-Russia Strategic Stability Dialogue had restarted with the goal of resuming negotiations on an agreement or agreements to supersede New START. But Vladimir Putin's decision to discard diplomacy launch Russia's brutal invasion of Ukraine has sidelined the talks indefinitely.

Although Putin’s regime must suffer international isolation now, U.S. and Russian leaders must eventually seek to resume talks through their stalled strategic security dialogue to defuse broader NATO-Russia tensions and maintain common sense arms control measures to prevent an all-out arms race.

Russia’s December 2021 proposals on security and the Biden administration's responses show there is room for negotiations to resolve mutual concerns, including agreements to scale back large military exercises and prevent the deployment of intermediate-range missiles in Europe or western Russia. Washington must test whether Russia is serious about such options.

During and after the Cold War, leaders and Washington and Moscow have had deep differences on many issues and faced many crises. Through it all, they have come to recognize that their common enemy is nuclear arms racing and nuclear war. In the introduction to his 1980 memoir about the negotiation of SALT, Gerard Smith wrote:

"In this springtime of 1980 as the Afghan snows are melting, the Soviet aggression continues and the second SALT agreements are in Senate suspense. It is natural to wonder whether the whole SALT process is coming to a close and whether it was or is worthwhile. I think so. It is better to have the strategic arms of an aggressive Soviet Union under some international control than not."

Today, Russia and the West still have a mutual interest in resuming negotations designed to strike agreements that further slash bloated strategic nuclear forces, regulate shorter-range “battlefield” nuclear arsenals, and set limits on long-range missile defenses before 2026. At the very least, the U.S. and Russian presidents should agree to issue unilateral reciprocal commitments to respect the central limits of New START after its expiry. Otherwise, our common future will be even riskier.