The United States and Russia aim to meet early next year for further talks on the future of arms control to follow the expiration of the last remaining agreement on the two countries’ nuclear arsenals in four years.

This will mark the third round of the bilateral Strategic Stability Dialogue since U.S. President Joe Biden took office in January and met in person with Russian President Vladimir Putin in June. The first round took place in July, and the second occurred in September, during which two working groups were formed. These groups are officially named the “Working Group on Principles and Objectives for Future Arms Control” and the “Working Group on Capabilities and Actions with Strategic Effects.”

Washington and Moscow agreed after the September dialogue that “the two working groups would commence their meetings, to be followed by a third plenary meeting,” according to the joint statement released afterwards. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, who led the U.S. delegation in the dialogue, said Oct. 1 that the two working groups will be able to use the time before the next plenary meeting “to dig into the details on a wide range of issues of importance to the two delegations.”

Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov, who led the Russian delegation, added Dec. 2 that “we have been working on their agenda in the most intensive way.”

The Biden administration initially expressed its desire to hold the third round of the dialogue by the end of 2021, but Secretary of State Tony Blinken said Dec. 2 that the schedule shifted to early 2022. Biden and Putin discussed the dialogue during a Dec. 7 videoconference, though no further details on the conversation were given. Russian officials have suggested they believe the dialogue will be more productive after the release of the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, which is slated for early 2022.

In a joint statement, Washington and Moscow described the second round of talks as “intensive and substantive.” A senior U.S. administration official further told Reuters Sept. 30 that “this was a good building-on of the meeting that we had in July, [with] both delegations really engaging in a detailed and dynamic exchange.”

Both sides have emphasized since September that the most recent dialogues are only the starting point of their conversations about strategic stability and arms control. While the two countries “have many discords, disagreements, and contradictory views on things, and only a few points of convergence,” Ryabkov said Oct. 1, “there are no unbridgeable gaps” so long as “political will and readiness for creative diplomacy prevail on both sides.”

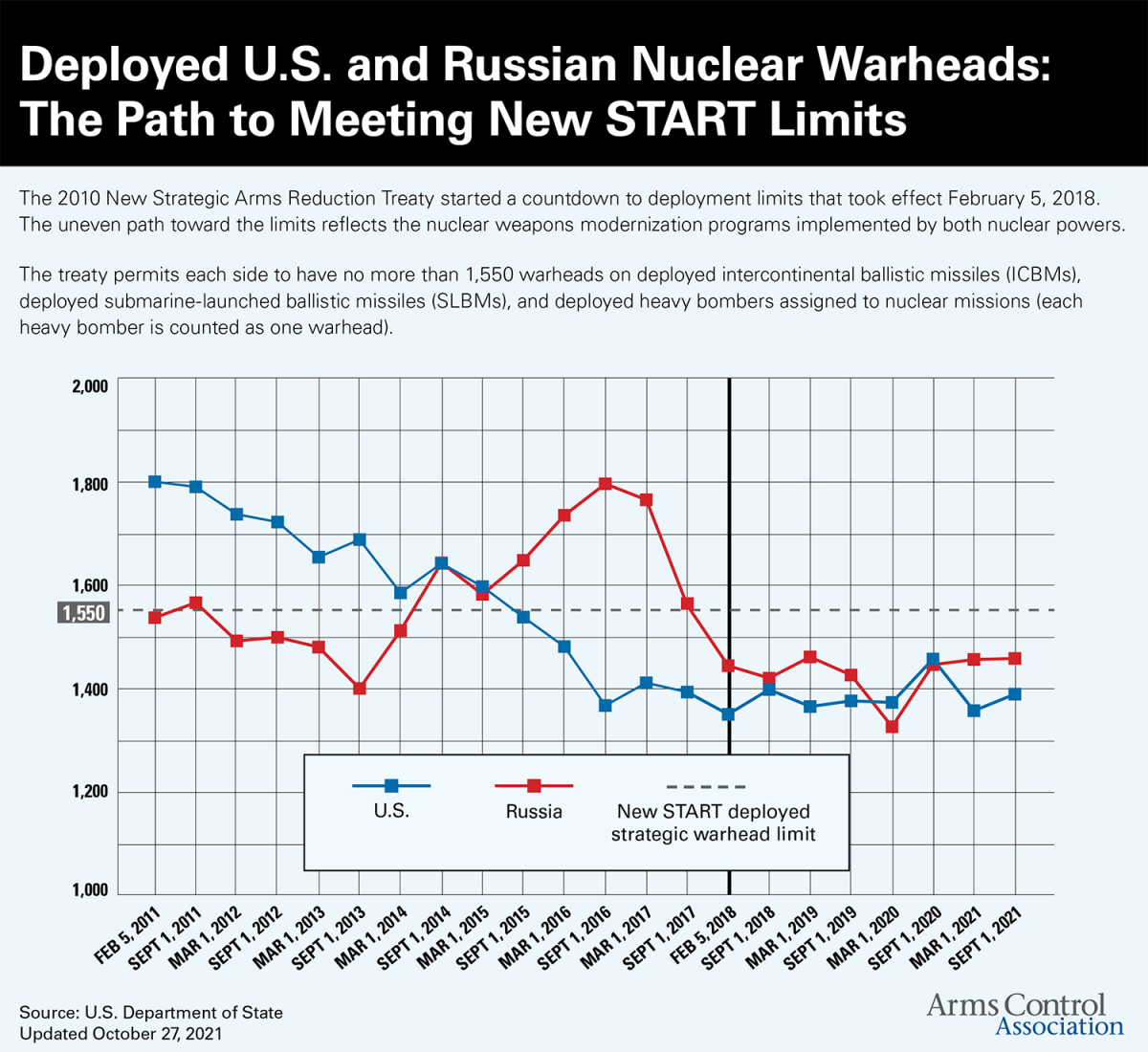

Meanwhile, the United States and Russia continue to adhere to the limits on their strategic nuclear arsenals imposed by the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), as revealed by a September data exchange between the two sides. The treaty caps U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals at 1,550 deployed warheads and 700 deployed delivery vehicles and heavy bombers each and will expire in 2026.

On-site inspections conducted under New START remain under the suspension begun in March 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic. Ryabkov said Dec. 13 that “the practice of mutual inspection visits will resume as the sanitary situation improves.”

The Bilateral Consultative Commission, the treaty’s implementing body, restarted its meetings for the first time since the start of the pandemic Oct. 5-14 in Geneva. —SHANNON BUGOS, Senior Policy Analyst

U.S., Russia Outline Respective Arms Control Priorities

Washington and Moscow restarted the bilateral strategic stability dialogue this year with differing agendas. Consequently, Ryabkov said Oct. 1 that “an exchange of our respective threat perceptions and security concerns” served as the “first substantial step” of the dialogue.

In a Sept. 6 NATO address, her first remarks as undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, Bonnie Jenkins described the Biden administration’s approach to the future of arms control with Russia. She said that U.S. efforts “are guided by several key concepts,” which include seeking to limit new kinds of intercontinental-range nuclear delivery systems; address all nuclear warheads, such as nonstrategic, or tactical, nuclear weapons; and maintain the limits imposed by New START. She added that the administration has also prioritized pursuing new risk reduction measures with China.

On the same day, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg expressed that the alliance also wants to see more systems incorporated into arms control, such as nonstrategic weapons as well as emerging and disruptive technologies like autonomous platforms and artificial intelligence. He echoed Jenkins’ call for China to partake in arms control, saying “Beijing too would benefit from mutual limits on numbers, increased transparency, and more predictability.”

Russia, meanwhile, has sought to develop “a new security equation” that addresses all nuclear and non-nuclear, offensive and defensive weapons that affect strategic stability. This would include discussions on U.S. missile defense systems, which Washington has long resisted putting on the table, as well as on the prevention of an arms race in outer space.

Moscow has also called for the inclusion of France and the United Kingdom in arms control in response to U.S. efforts to pull in China and insisted that Washington must first withdraw its tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Europe before any discussion on Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons could take place.

The two working groups formed in the fall will attempt to work out the differences between the U.S. and Russian agendas on strategic stability.

The new groups are different from those established by the Trump administration that focused on nuclear warheads and doctrine, verification, and space. The new working group on future arms control might aim, for instance, to outline the scope of what agreement could follow after New START expires in 2026. Ryabkov has said that what may come next could be “a legally binding document, perhaps not one, but several texts, both legally and politically binding, if such an option is deemed preferable by both parties.”

The other new working group on capabilities and actions with strategic effects might cover discussion on issues such as long-range conventional or dual-capable precision fires, such as hypersonic weapons, and tactical nuclear weapons.

It remains unclear whether, how, or when the Biden administration plans to transition the strategic stability dialogue to more formal negotiations on an arms control agreement or another arrangement to follow New START. President Biden said in June that “we’ll find out within the next six months to a year whether or not we actually have a strategic dialogue that matters.”

Russia Completes Open Skies Treaty Withdrawal

Russia officially left the 1992 Open Skies Treaty on Dec. 18, leaving the now 32-member treaty without two of the main players considering the U.S. withdrawal last year.

“Responsibility for the deterioration of the Open Skies regime lies fully with the United States as the country that started the destruction of the Treaty,” said the Russian Foreign Ministry in a Dec. 18 statement.

The Trump administration withdrew the United States from the accord in November 2020, and Washington informed Moscow in May that it would not seek to rejoin the treaty. Russian President Vladimir Putin signed off in June on the decision to kickstart the six-month withdrawal process.

Following the U.S. withdrawal, Moscow sought written guarantees from the remaining states-parties that they would neither continue to share data collected under the treaty with the United States nor prohibit overflights of U.S. bases in Europe, but states-parties dismissed the request.

“Regrettably, all our efforts to preserve the Treaty in its initial format have failed,” said the ministry’s statement. “The Treaty fell victim to the infighting of various influence groups in the United States, where hawks gained the upper hand. Washington set the line towards destroying all the arms control agreements it had signed.”

Ann Linde, chairperson-in-office of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), expressed regret Dec. 13 that “the deficit of trust has grown so strong that key countries have decided to leave the Treaty on Open Skies. I hope that they will reverse their decisions.”

Russia formed a group of states-parties under the treaty with Belarus. Minsk initially seemed to plan to withdraw from the treaty alongside Moscow but now seems likely to remain party to the treaty, tweeted Alexander Graef, a researcher at the Institute for Peace, Research, and Security Policy in Hamburg, on Dec. 17.

A next step for the remaining states-parties will be the redistribution of flight quotas for 2022, as during the usual conference in October to determine quotas, some requested overflights of Russia.

“What is important now is for the remaining states to continue implementation, modernize the Treaty (digital cameras and new sensor types), and seriously discuss additional forms of use, i.e., cross-border disaster relief or environmental monitoring,” said Graef.

Entering into force in 2002, the Open Skies Treaty permits each state-party to conduct short-notice, unarmed observation flights over the others’ entire territories to collect data on military forces and activities.

Russia Includes INF Moratorium in Security Proposals to U.S., NATO

Russia demanded the United States not deploy missiles formerly banned under the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty outside its borders in the draft security agreements Moscow proposed to the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Dec. 15.

Under the INF treaty, the United States and Soviet Union agreed to ban all nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers, leading to the elimination of a total of 2,692 missiles.

After Washington withdrew from the accord in 2019, Russian President Vladimir Putin proposed that the two countries impose a moratorium on the deployment of INF-range missiles and later added mutual verification measures to the proposal. The Trump administration and NATO dismissed the Russian proposal at the time.

Karen Donfried, assistant secretary of state for the bureau of European and Eurasian affairs, met with Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov on Dec. 15, during which Ryabkov handed over two separate draft agreements on obtaining security guarantees from each the United States and NATO.

“We hope that the United States will enter into serious talks with Russia in the near future regarding this matter, which has critical importance for maintaining peace and stability, using the Russian draft treaty and agreement as a starting point,” said the foreign ministry in a Dec. 17 statement.

In the draft U.S.-Russian agreement, Article VI states that the two countries “shall undertake not to deploy ground-launched intermediate-range and shorter-range missiles outside their national territories, as well as in the areas of their national territories, from which such weapons can attack targets in the national territory of the other Party.”

In the draft NATO-Russian agreement, Article V also includes a moratorium proposal, saying that “the Parties shall not deploy land-based intermediate- and short-range missiles in areas allowing them to reach the territory of the other Parties.”

Additionally, Moscow proposed that the United States and Russia “refrain from deploying nuclear weapons outside their national territories” in Article VII. This article also calls for the two countries to “not train military and civilian personnel from non-nuclear countries to use nuclear weapons.”

This part of the proposed document likely refers to the nuclear sharing agreement between the United States and NATO, under which Washington is estimated to deploy around 100 B61 gravity bombs across Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey, with all but the Turkish air forces assigned and trained to carry out nuclear strike missions with the U.S. weapons.

Meanwhile, the preamble of the draft U.S.-Russian agreement reiterates the 1985 Reagan-Gorbachev principle that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” which Presidents Biden and Putin reaffirmed during their June summit.

NATO officials have rejected the Russian proposed agreement.

As for the U.S.-Russian draft agreement, Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security advisor, said Dec. 17 that Washington is willing to use it as the basis for negotiations.

“We’ve had a dialogue with Russia on European security issues for the last 20 years,” Sullivan said. “We had it with the Soviet Union for decades before that.” The Biden administration will plan “to put on the table our concern with Russian activities that we believe harm our interests and values,” he added.

U.S., Russia Convene with Other Nuclear Powers in Paris

Representatives of the five original nuclear-armed states gathered for the first time in nearly two years in Paris Dec. 2-3 to discuss preparations ahead of the 10th Review Conference for the 1968 nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), which begins January 4 in New York.

The five NPT-recognized nuclear-weapon states—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—released a joint communiqué following the conference in which they reaffirmed their commitment to Article VI of the treaty and expressed their support for “the ultimate goal of a world without nuclear weapons with undiminished security for all.”

Article VI commits the countries to pursue “negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.” Non-nuclear-weapon states have long expressed frustration with the five nuclear powers over their commitment to and progress on this article in light of expanding nuclear arsenals and nuclear weapon modernization.

According to the communiqué, the five countries “reviewed progress achieved concerning the different workstreams under the P5 Process in preparation” for the NPT Review Conference. They exchanged updates on their respective nuclear doctrines and policies and recommitted to ongoing discussions on these subjects, recognized “their responsibility to work collaboratively to reduce the risk of nuclear conflict,” and communicated an intent “to build on their fruitful work on strategic risk reduction within the P5 Process in the course of the next NPT review cycle.”

The P5 have announced they will hold a side event at the NPT Review Conference focused on their nuclear doctrines and policies.

Missing from the joint communiqué was a reference to the “nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought” statement endorsed by Presidents Biden and Putin at their June 2021 summit in Geneva and originally declared by Presidents Reagan and Gorbachev in 1985. At the 2020 P5 Process gathering, the United States balked at a proposal put forward by China for a joint declaration on this principle.

Diplomatic sources tell the Arms Control Association that the P5 may issue another joint statement on nuclear risk reduction in January.

The five nuclear-weapon states are also the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, known as the P5. This meeting in Paris was part of the P5 Process, which was established in 2009 with an agenda focused on a shared glossary of key nuclear terms; nuclear doctrines and strategic risk reduction; a prospective fissile material cutoff treaty; peaceful nuclear uses; and nuclear-weapon-free-zones.

France chaired the P5 process for 2021, and the United States will take over in the new year. The P5 process was last convened in person in February 2020.

Commission Outlines Pathways for U.S.-Russian Arms Control

This week, a group of 21 Russian, U.S., and European nuclear and security experts issued a joint statement outlining recommendations for how U.S. and Russian negotiators can tackle several tough issues on their future nuclear arms control agenda. The group, known as the Deep Cuts Commission, was established in 2013.

“In order to seize opportunities to reduce nuclear dangers, both sides need to move swiftly and decisively,” the statement reads. “A top priority has to be the search for a follow-on agreement or agreements to the 2010 New START Treaty, the last remaining bilateral treaty capping the world’s two largest arsenals, before it expires in early 2026. U.S. and Russian leaders should also explore other measures to reduce nuclear dangers, prevent new arms races, and prepare the ground for inclusion of additional nuclear powers in the arms reduction effort.”

The full statement, “How the U.S.-Russian Strategic Stability Dialogue Can and Must Make Progress,” is available online here.

FACT FILE

NEW RESOURCES & ANALYSES

- “Reimaging Nuclear Arms Control,” by James Acton, Thomas MacDonald, and Pranay Vaddi, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Dec. 16, 2021

- "US-Russia Strategic Stability Dialogue: Purpose, Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities," by Leonor Tomero, Russia Matters, Dec. 15, 2021

- “Focusing the Message: Immediate Priorities for U.S.-Russian Arms Control,” by Artem Kvartalnov, Noah Mayhew, and Daria Selezneva, Deep Cuts Commission, Nov. 4, 2021

- “Bilateral strategic stability: What the United States should discuss with Russia. And China,” by Robert J. Goldston, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Oct. 14, 2021

- “Strengthen U.S. Security Through Nuclear Arms Reductions,” by Rep. Ami Bera and Steven Pifer, Defense One, Sept. 29, 2021

- “End of an Era: The United States, Russia, and Nuclear Nonproliferation,” edited by Sarah Bidgood and Bill Potter, James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, August 2021

ON OUR CALENDAR

- Dec. 8: 34th Anniversary of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty

- Jan. 3: 20th Anniversary of the Strategic Arms Reductions Treaty II (START II)

- Jan. 4-28: 10th Review Conference for the 1968 nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), New York City