Russia Puts Open Skies Withdrawal Process Into Motion

Russia formally started the process for withdrawing from the 1992 Open Skies Treaty in May, further dampening prospects for the embattled agreement.

Russian President Vladimir Putin submitted to the State Duma May 11 a bill to withdraw Russia from the treaty. With the U.S. withdrawal from the accord last year, “serious damage was inflicted upon treaty compliance and its role in promoting confidence building measures and strengthening transparency,” the bill reads. “A threat to the national security of the Russian Federation has emerged.”

State Department Spokesperson Ned Price later that day said that the Biden administration still has yet to decide on the future of potential U.S. participation in the treaty. “We are at the moment actively reviewing matters related to the treaty,” he told the press. “Importantly, we are consulting with our allies and partners as we always do on these matters.”

At the time of the U.S. withdrawal in November, President Joe Biden had condemned the decision as illustrative of President Donald Trump’s "short-sighted policy of going it alone and abandoning American leadership.”

To become law, the Russian bill requires three affirmative votes in the lower house of the Russian parliament, the State Duma, and one affirmative vote in the upper house, the Federation Council, with Putin’s signature as the final step.

Putin’s move came after Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin signed a May 4 decree “to approve and submit to the President of the Russian Federation…a proposal to denounce the Open Skies Treaty.”

Moscow began in January domestic procedures for withdrawing from the treaty and has since said it plans to conclude those procedures by the end of May, at which point it would notify states-parties and kick-start the six-month period before the withdrawal officially takes place. In December 2020, Russia sought written guarantees from the remaining states-parties to address its concerns following the U.S. withdrawal (including that Washington might maintain access to information obtained under the treaty through its allies or block flights over U.S. bases in Europe), but multiple states-parties dismissed Moscow’s request.

However, Russia has said that it would reconsider its move to withdraw from the accord if the United States returned to the agreement. Lavrov commented April 8 that Moscow would “respond constructively and reconsider” its plan to withdraw if Washington decided to rejoin the treaty but that Russia “cannot wait indefinitely.”

Defense News reported April 7 that the State Department sent a diplomatic note to allies and partners March 31 expressing concern that “agreeing to rejoin a treaty that Russia continues to violate would send the wrong message to Russia and undermine our position on the broader arms control agenda.”

“While we recognize that Russia’s Open Skies violations are not of the same magnitude as its material breach of the 1987 INF [Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces] Treaty, they are part of a pattern of Russian disregard for international commitments—in arms control and beyond—that raises questions about Russia’s readiness to participate cooperatively in a confidence-building regime,” the note read according to Defense News.

But the note reportedly also said that the administration believes “there are circumstances in which we return to” the treaty “or include some of” the treaty’s “confidence-building measures under other cooperative security efforts.” However, discussions within the Open Skies Consultative Commission, the implementing body of the treaty, have reportedly not been going well, suggesting little hope that Washington will return to the accord.

Signed in 1992 and entering into force in 2002, the treaty permits each state-party to conduct short-notice, unarmed observation flights over the others’ entire territories to collect data on military forces and activities. Treaty proponents say such information-sharing promotes stability. —KINGSTON REIF, director for disarmament and threat reduction policy, and SHANNON BUGOS, research associate

NEW START

U.S., Russia Discuss Resumption of Arms Control Dialogue

U.S. President Joe Biden proposed during an April 13 call with Russian President Vladimir Putin that the two countries hold a wide-ranging summit meeting in the coming months that could pave the way to a regular strategic stability dialogue on arms control and security issues and perhaps formal negotiations on new arms control arrangements.

The summit would take place in a third country—Austria, Finland, and Switzerland have since offered to host—and feature discussions on “the full range of issues facing the United States and Russia,” the White House said in a statement after the call. A Kremlin official has said the summit may occur in June, and Biden said in May that it is his “hope and expectation” to have the meeting next month.

“Out of that summit—were it to occur, and I believe it will—the United States and Russia could launch a strategic stability dialogue to pursue cooperation in arms control and security,” added Biden April 15. The United States and Russia first met for a strategic stability dialogue in Helsinki in September 2017 and last held the dialogue in Vienna in August 2020.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov commented April 16 that Moscow has “responded positively” to the proposal. “Now we are studying different aspects of this initiative,” he said.

During their call, Biden and Putin discussed “the intent of the United States and Russia to pursue a strategic stability dialogue on a range of arms control and emerging security issues, building on the extension” of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), according to the White House. Washington and Moscow agreed in February to extend the treaty for five years, and both expressed a willingness to pursue further engagement on arms control.

While the strategic stability dialogue would likely be separate from any future negotiations on a potential arms control agreement to follow New START, it could serve as a venue to set the foundation for formal follow-on talks.

Secretary of State Tony Blinken said in February that the United States would pursue “arms control that addresses all of its [Russia’s] nuclear weapons,” including Russia’s large stockpile of non-strategic, or tactical, nuclear weapons. Lt. Gen. Scott Berrier, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, said April 26 that “Russia probably possesses 1,000 to 2,000 nonstrategic nuclear warheads.”

Nearly 40 Democratic members of Congress, led by the four co-chairs of the Nuclear Weapons and Arms Control Working Group, sent an April 20 bicameral letter to Biden urging his administration to “work expeditiously to pursue talks with Russia on a follow-on agreement that can safely achieve deeper, verifiable reductions in both sides’ excessive strategic nuclear arsenals.”

The talks, the members wrote, should also address “mutual understandings with Russia on limitations on strategic missile defenses and the development of new hypersonic weapons, as well as other new technologies that could threaten progress on practical measures to reduce the chance of an inadvertent nuclear war.”

Melissa Dalton, acting assistant secretary of defense for strategy, plans, and capabilities, told the House Armed Services Committee April 21 that the Biden administration believes China should “take its seat at the table” on arms control. Beijing has a total nuclear warhead stockpile in the low-200s, according to an estimate by the Defense Department. The Biden administration expects “China to accept its responsibility as a nuclear-armed, technologically advanced power, which includes increased transparency and progress on nuclear security,” said Dalton.

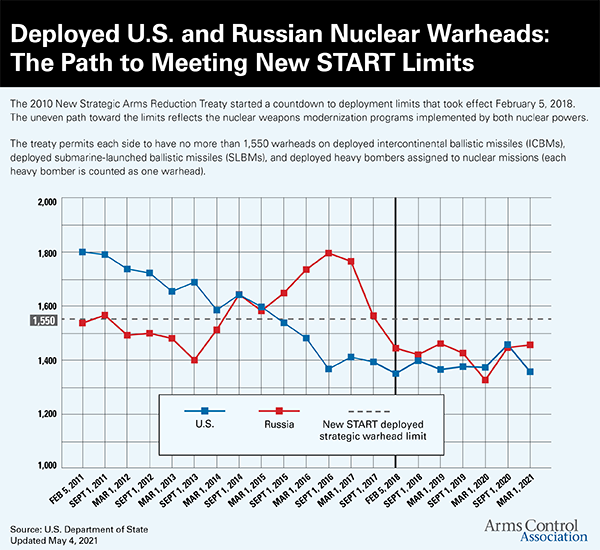

New START caps the U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals at 1,550 deployed warheads and 700 deployed missiles and heavy bombers each. Inspections under the treaty and meetings of the Bilateral Consultative Commission, the implementing body of the treaty, have been suspended since early 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic.

U.S., Russia Meet New START Limits

The United States and Russia both remain at or below the limits set by New START, according to the first data exchange since the treaty was extended.

As of March 1, the United States deploys 1,357 warheads on 651 missiles and heavy bombers and has 800 deployed and nondeployed launchers and bombers. Russia deploys 1,456 warheads on 517 delivery systems and has 767 deployed and nondeployed launchers and bombers.

Though the U.S. and Russian strategic arsenals have fluctuated since the treaty’s implementation deadline in 2018, both Washington and Moscow have consistently stayed within the treaty’s limits.

Adm. Charles Richard, commander of U.S. Strategic Command, emphasized during an April 20 hearing before the Senate Armed Service Committee that these data exchanges are one of the “primary benefits” of the treaty, in addition to the limits imposed by the agreement.

“It’s the transparency and the confidence now that we have an understanding what that piece of the threat looks like,” he said. Richard added he was “pleased” to see the five-year extension of New START and encourages “efforts to get a similar degree of control and accountability on the remainder of the Russian arsenal, all of which is something I have to deter.”

INF TREATY

U.S. Military Debates Ground-Launched Missiles

As the Defense Department continues to develop conventional missiles formerly banned by the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, an internal debate within the department about the rationale for the missiles and uncertainty about where they might be based has spilled out into the open.

“I genuinely struggle with the credibility” of the Army’s plan to develop the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, Air Force Gen. Timothy M. Ray, chief of the Global Strike Command, said April 1 on an Air Force Association podcast. “I just think it’s a stupid idea to go invest that kind of money to re-create something that [the Air Force] has mastered,” he said.

The Army is developing a suite of ground-launched missiles with a range exceeding the 500-kilometer limit prohibited by the INF Treaty, including the Precision Strike Missile, a midrange missile capability, and the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon. The Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon is slated to have a range of several thousand kilometers, according to Army officials. The projected total cost of the weapon is unknown. Congress provided $861 million for the program in fiscal year 2021.

Several Pentagon officials have made a strong push for the development of longer-range ground-launched missiles to complement the long-range air and sea capabilities already provided by the Air Force and Navy. “A wider base of long-range precision fires…is critically important to stabilize what is becoming a more unstable environment in the western Pacific,” Adm. Philip Davidson, the head of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, told the Senate Armed Services Committee March 9. The Army and Marine Corps are enthusiastic “to embrace some of the capabilities that the Navy and Air Force have already developed,” Davidson added.

But Ray’s criticism of the Army’s plans suggests the Pentagon is not unified on the best way forward for the long-range strike mission. “Why would we entertain a brutally expensive idea, when we don’t, as a department, have the money?” he asked in reference to the projected cost of the Army’s long-range missile efforts.

Ray also raised questions about the ability of the Army to find basing options for the weapons. The Army, he said, is trying to “skate right past that brutal reality to check that some of those countries are never going to let you put…stuff like that in their theater…Just go ask your allies.”

To read more, see: “U.S. Military Debates Ground-Launched Missiles,” Arms Control Today, May 2021

STRATEGIC STABILITY

U.S. Retires First Open Skies Plane, Second Close Behind

The United States officially retired one of its two Boeing OC-135B aircraft used for overflight missions under the 1992 Open Skies Treaty May 7, fueling concerns that the Biden administration may not return the United States to the accord.

The news, first reported by the Omaha World-Herald, came a month after the paper discovered the Air Force’s plan to send the two aircraft to the scrapyard at David-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona this spring. The second plane will be retired June 4.

The Air Force will also dispose of the suite of cameras, called sensors, on the planes after spending $41.5 million in fiscal year 2020 to replace the wet-film cameras with new digital sensors for both aircraft. The Trump administration’s fiscal year 2021 budget request did not include any request for overflight funding. At the time of the U.S. withdrawal in November 2020, a senior U.S. official said that the Pentagon had begun to liquidate the equipment.

The Biden administration has “determined they’re not going to do Open Skies anymore,” Rep. Don Bacon (R-Neb.) told the Omaha World-Herald in April. “It treats it as matter-of-fact that we’re out of the treaty,” he said, adding, “I wish it wasn’t that way, but it is.”

But a spokesperson for the National Security Council told The Wall Street Journal April 5 that the administration’s decision on U.S. participation in the accord “is separate from previously scheduled activities relating to aging equipment.”

Instead of flying its own equipment, the United States could resume participation in the treaty by working with allies who are states-parties on joint missions and using their aircraft for overflights.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said April 8 that Russia does not have “any idea whether the Americans will return to the treaty or not, but we hope that this matter will be sorted out soon.”

U.S. Casts Doubt on Russian Treaty Compliance

The United States lodged concerns regarding Russian compliance with treaties such as the Open Skies Treaty and certified Moscow’s compliance with New START despite questions about implementation, according to an annual report released April 15.

This marks the first publication of the annual compliance report by the State Department under the Biden administration, although it covers activities during 2020 under the Trump administration.

The report expressed concerns that Russia is in violation of the Open Skies Treaty because it has limited the distance for observation flights over the Kaliningrad region to no more than 500 kilometers and prohibited missions over Russia from flying within 10 kilometers of its border with the conflicted Georgian border regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. The report acknowledged a February 2020 overflight by the United States, Estonia, and Lithuania that traveled 505 kilometers, but said “Russia made clear in 2020 that it had not yet changed its standing policy” regarding the restriction.

The State Department noted that the United States is no longer a state-party to the treaty after the Trump administration withdrew in November 2020. As such, the treaty will not be included in the report going forward unless Washington decides to rejoin.

In addition, the report said that Russia has continued to undertake activities that are inconsistent with the “zero yield” standard regarding nuclear testing, established through negotiations on the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), which prohibits all nuclear test explosions regardless of yield. The State Department added that its concerns were suspended for activities occurring in 2020 “because Russia’s activities may have been curtailed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

As for New START, which the United States and Russia extended in February until 2026, the State Department certified Russian compliance with that pact despite some unspecified “implementation-related questions.”

On April 21, Russian Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova denounced the report, saying that its “lack of any conclusive evidence, its dissemination of blatantly false accusations, and suppression of Washington’s own imperfect compliance with arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament agreements relegate it to the category of information noise.”

The report asserted that the United States “continued to be in compliance with all of its obligations under arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament agreements.”

FACT FILE

NEW RESOURCES & ANALYSES

- “Back From the Brink? Next Steps for Biden and Putin,” by Daryl Kimball, Arms Control Today, May 2021

- “The Future of Strategic Arms Control,” by Rebecca Lissner, Council on Foreign Relations, April 2021

- “The Biden-Putin summit: Do the risks outweigh the potential rewards?” by William Courtney, The Hill, April 27, 2021

- “Biden can make history on nuclear arms reductions,” by William D. Hartung, The Hill, April 15, 2021

- “Can Biden Go Big on Arms Control With Russia?” featuring Sarah Bidgood, World Politics Review, April 14, 2021

- “First New START Data After Extension Shows Compliance,” by Hans Kristensen, Federation of American Scientists, April 6, 2021

- “How the Biden administration can secure real gains in nuclear arms control,” by Sharon Squassoni, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March 30, 2021

- “Reconsidering Arms Control Orthodoxy,” by Naomi Egel and Jane Vaynman, War on the Rocks, March 26, 2021

- “Responding to Troubling Trends in Russia’s Nuclear Weapons Program,” by Peter Brookes, Heritage Foundation, March 26, 2021

- “Building on George Shultz’s Vision of a World Without Nukes,” by William J. Perry, Henry A. Kissinger, and Sam Nunn, The Wall Street Journal, March 23, 2021

ON OUR CALENDAR

| May 17 | “Smarter Options on U.S. Nuclear Modernization,” Arms Control Association Briefing with Rep. Garamendi (D-Calif.) |

| June 11-13 | G-7 Summit, United Kingdom |

| June 14 | NATO Summit, Belgium |