Since securing the extension of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) in February, the United States and Russia have both signaled a willingness to hold a dialogue on arms control as part of a broader conversation on strategic stability, though when exactly such discussions may take place remains unclear.

“The United States is ready to engage Russia in strategic stability discussions on arms control and emerging security issues,” said U.S. Secretary of State Tony Blinken at the Conference on Disarmament (CD) on Feb. 22.

The Biden administration released interim national security guidance on March 3 stating that “We will head off costly arms races and re-establish our credibility as a leader in arms control. That is why we moved quickly to extend the New START Treaty with Russia. Where possible, we will also pursue new arms control arrangements.”

Meanwhile, Russian President Vladimir Putin suggested on Feb. 11 that the two countries begin to “discuss other steps aiming to curb the arms race and to facilitate overall arms control.”

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov also addressed the CD on Feb. 24 and said that, with New START’s extension, “foundations were laid for further negotiations on arms control with due consideration of all factors affecting strategic stability.”

Moscow is “waiting for the new appointees to sit down in the State Department [and] in the White House” before holding arms control talks, according to Russian Ambassador to the United States Anatoly Antonov. Amb. Bonnie Jenkins, U.S. President Joe Biden’s nominee to be undersecretary of state for arms control and international security affairs, has yet to have her confirmation hearing scheduled.

“We have everything the sides need for resuming the strategic bilateral dialogue,” Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov said Feb. 11. “We are willing to start working on this without delay, as soon as Washington is ready.”

When dialogue between the United States and Russia might occur is uncertain. The next round of talks will likely be contentious as each side brings to the table its own list of concerns to address.

The United States has expressed concern about Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons and new long-range nuclear weapon delivery systems. The Biden administration has also said that it wants to hold discussions with China on arms control, though not on a trilateral basis as demanded by its predecessor.

“Working with our allies and partners, the United States will…demand greater transparency regarding China’s provocative and dangerous weapons development programs, and continue efforts aimed at reducing the dangers posed by their nuclear arsenal,” said Blinken in his CD address.

The Biden administration’s interim guidance also mentioned that Washington will “engage in meaningful dialogue with Russia and China on a range of emerging military technological developments that implicate strategic stability.”

Moscow has said that in future talks it would like to develop a new “strategic equation” that would take into account U.S. missile defense, hypersonic weapons, missiles formerly banned by the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, and the prevention of an arms race in space.

China, which repeatedly rejected efforts by the Trump administration to join trilateral arms control talks, has continued to point to its much smaller nuclear arsenal as justification. But Beijing said it is amenable to bilateral discussions on strategic stability issues.

The Defense Department estimates that Beijing has a nuclear arsenal in the low 200s, while Washington and Moscow each have total inventories of about 6,000, according to open-source estimates.

Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan will meet with China’s Director of the Office of the Central Commission for Foreign Affairs Yang Jiechi and State Councilor Wang Yi in Alaska on March 18. The U.S. delegation plans to “discuss a range of issues” with the Chinese officials, according to a March 10 statement from the State Department. Blinken emphasized to the House Foreign Affairs Committee the same day that “this is not a strategic dialogue” and “there’s no intent at this point for a series of follow-on engagements.”

Russia has reiterated its stance that it will not force Beijing to come to the table and that if Washington insists on China’s inclusion, then France and the United Kingdom must be brought in as well.

“We will never try to persuade China,” said Lavrov on Feb. 19. “We respect the position of Beijing, which either wants to catch up with us or proposes that we first reduce our arsenals to China’s levels and then start on the talks. All circumstances considered, if this is a multilateral process, then we will get nowhere without the United Kingdom and France.”

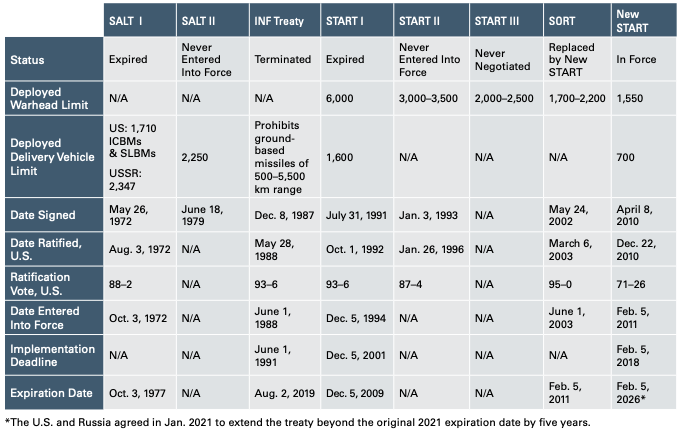

Signed in 2010, New START caps the U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals at 1,550 deployed warheads and 700 deployed missiles and heavy bombers each. The United States and Russia officially sealed a five-year extension of the treaty on Feb. 3, two days before it was set to expire. —KINGSTON REIF and SHANNON BUGOS

NEW START

U.S. Military Expresses Support for New START Extension

The uniformed U.S. military had yet to weigh in on the official extension of New START until supportive remarks by the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in late February.

During the Air Force Association’s Aerospace Warfare Symposium on Feb. 25, Gen. John Hyten spoke out in favor of the five-year extension and insisted that the treaty’s extension should be the beginning of a larger arms control discussion with Russia and China

“We just extended the New START Treaty, which I think is a good thing,” he said. “I think Adm. Richard at [U.S. Strategic Command] thinks it’s a good thing. I know the Chairman [of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley] thinks it’s a good thing.”

In the past, high-ranking service members have spoken to the importance of the treaty’s on-site inspections and verification regime for military intelligence and planning purposes.

Inspections under New START and meetings of the Bilateral Consultative Commission, the implementing body of the treaty, have been suspended since early 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic. But Ryabkov said on Feb. 11 that Washington and Moscow have launched efforts to restart the inspections.

INF TREATY

Russia Warns U.S. Against INF-Range Missile Deployment

The commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command is calling for the development of long-range, ground-based precision strike weapons, to include missiles formerly banned by the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, though Russia warned that such a move could trigger a new arms race.

“A wider base of long-range precision fires, which are enabled by all our terrestrial forces—not just sea and air but by land forces as well—is critically important to stabilize what is becoming a more unstable environment in the western Pacific,” Adm. Philip Davidson told the Senate Armed Services Committee in a March 9 hearing.

Signed in 1987, the INF Treaty led to the elimination of 2,692 U.S. and Soviet nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. The Trump administration withdrew the United States from the treaty in August 2019, citing Russian noncompliance.

“U.S. ground formations must have long-range weapons in the western Pacific to include SM-6 and Maritime Strike Tomahawk,” Davidson said in his testimony. The U.S. Army first announced in November the selection of those two missiles as the basis for the initial development of a conventional, ground-launched, mid-range missile capability. The Army and Marine Corps are enthusiastic “to embrace some of the capabilities that the Navy and Air Force have already developed,” Davidson said.

Gen. James McConville, chief of staff of the Army, also made the case for this capability, telling reporters March 11 that “The value of land-based is it’s 24/7. So, it’s always there.” The Army’s efforts to employ “long-range precision effects and long-range precision fires” are meant to “provide commanders in the global campaign with multiple options,” he said.

Russia quickly denounced Davidson’s testimony and warned of the potential fallout should the United States move ahead with the deployment of these missiles.

“We want to point out again that the deployment of American land-based intermediate-range and shorter-range missiles, regardless of what they carry, in various parts of the world, including in the Asia-Pacific Region, would have an immensely destabilizing effect in terms of international and regional security,” said Russian Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Maria Zakharova on March 12. “This would provoke a new round of the arms race, the implications of which can hardly be predicted.”

Zakharova also reiterated Moscow’s proposal of a moratorium on the deployment of missiles previously banned under the treaty, along with some mutual verification measures. The Trump administration, as well as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, had previously dismissed the proposal.

Davidson’s testimony came after Indo-Pacific Command sent to Congress on March 1 its list of spending priorities, which included a request for $408 million for “ground-based, long-range fires” for fiscal year 2022 and $2.9 billion for the item for fiscal years 2023 through 2027. “Long-range fires” is one of the programs under review by Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks ahead of the Pentagon’s release of the fiscal year 2022 budget request, according to a Feb. 24 Politico report.

Davidson is expected to retire this year, and in early March, the Biden administration officially nominated Adm. John Aquilino to be the commander of Indo-Pacific Command.

STRATEGIC STABILITY

Russia to Initiate Open Skies Withdrawal by Summer Unless U.S. Returns

Russia will likely complete the domestic procedures for withdrawing from the 1992 Open Skies Treaty by this summer, after which it will submit official notice to the states-parties. But Moscow said it could reverse the decision should the United States return to the treaty.

“In our estimates, they [the domestic procedures] may be completed by the summer of this year,” said Konstantin Gavrilov, the Russian head of negotiations in Vienna on military security and arms control, on Feb. 22. “If the United States does not inform us before that time about its readiness to return to the treaty framework,” he continued, Russia will give its official notice of withdrawal to the treaty’s depositories, Canada and Hungary. Once states-parties are notified, Moscow could officially withdraw in six months, as stipulated by the treaty text.

The United States withdrew from the Open Skies Treaty in November 2020. Moscow announced on Jan. 15 that it would pursue the domestic procedures required for withdrawal, though Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov first suggested Feb. 11 that if Washington expressed a readiness to return to the treaty, “we might somehow adjust the decision to launch internal procedures.”

“But nobody should expect Russia to make any concession,” he added.

The Biden administration is in the process of reviewing the potential future of U.S. participation in the treaty. Gen. Charles Brown, chief of staff of the U.S. Air Force, said Feb. 17 that he sees “value in the Open Skies [Treaty], in the ability for both nations to be open and transparent.”

“So, I’ll wait for guidance from the administration when they ask for my assessment,” he said. The Air Force operates the two Boeing OC-135B aircraft used for treaty overflight missions, and a U.S. defense official said in November that the liquidation of the planes had already begun.

RIA Novosti, a Russian news agency, reported in January that Moscow plans to repurpose the two Tu-214ON aircraft used for treaty overflights for other missions, primarily for reconnaissance, following an official treaty withdrawal. RIA then reported that one of the aircraft performed an “observation and reconnaissance flight along the coasts of the Krasnodar territory and Crimea” and “tested the ability of the regional air defense system” on March 4.

Signed in 1992 and entering into force in 2002, the Open Skies Treaty permits each state-party to conduct short-notice, unarmed observation flights over the others’ entire territories to collect data on military forces and activities.

France Aims to Convene P5

France intends to convene a meeting of five nuclear-weapon states—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—in the coming months in an attempt to make progress on the group’s work plan, which includes nuclear risk reduction.

Paris is the current coordinator of the P5 process, as it is commonly known, and is therefore responsible for organizing a formal meeting and coordinating agenda items.

The group last met in February 2020, at which time the Trump administration tried to convince China to join trilateral arms control talks with Russia.

With the United States wanting to include China in arms control and Russia wanting to bring in France and the United Kingdom, experts have encouraged the use of the P5 process to hold discussions on nuclear weapons issues and to perhaps become a genuine negotiating forum.

For more, see: “France to Coordinate P5 Process.”

FACT FILE

U.S.-Russian Strategic Nuclear Arms Control Treaties at a Glance

More in the March 2021 Arms Control Today.

NEW RESOURCES & ANALYSES

- “Arms Control Strategies for a New Administration,” by Rebecca Hersman and Suzanne Claeys, Center for Strategic and International Security, Feb. 4, 2021

- “With New START Extended, What Is Future of US-Russian Arms Control?” featuring Laura Kennedy, Michael Krepon, Emmanuelle Maître, Olga Oliker, and Steven Pifer, Russia Matters, Feb. 5, 2021

- “The President’s Authority to Rejoin the Open Skies Treaty,” by Jean Galbraith, Lawfare, Feb. 8, 2021

- “Post-New START Arms Control: Lessons from a U.S.-Russia Bilateral Expert Dialogue,” featuring Andrey Baklitskiy and Amy Woof, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Feb. 9, 2021

- “Biden’s Russia Policy Will Be Shaped by His Priorities, Not Just His People,” by Paul Saunders, Russia Matters, Feb. 18, 2021

- “What Biden and Putin Can Agree On,” by Bruce Allyn, Foreign Policy, Feb. 19, 2021

- “New START extension and next steps for arms control,” by Timothy Wright and Henry Boyd, International Institute for Strategic Studies, Feb. 19, 2021

- “The Nuclear Option,” by Jeffery Lewis, Foreign Affairs, Feb. 22, 2021

- “Back to Basics on Russia Policy,” by Eugene Remer and Andrew Weiss, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 9, 2021

- “The Future of U.S.-Russian Arms Control: Principles of Engagement and New Approaches,” by Heather Conley, Vladimir Orlov, Evgeny Buzhinsky, Cyrus Newlin, Sergey Semenov, and Roksana Gabidullina, Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 12, 2021

- “Negotiating with Putin’s Russia: Lessons Learned from a Lost Decade of Bilateral Arms Control,” by Michael Albertson, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, March 2021

ON OUR CALENDAR

| March 18 | Secretary of State Tony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan meet with China’s Director of the Office of the Central Commission for Foreign Affairs Yang Jiechi and State Councilor Wang Yi in Alaska |

| April 8 | 11th Anniversary of New START’s signing |

| April 26 | 35th Anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster |