This week, the British government announced that it would reverse decades of progress to reduce its lethal arsenal of nuclear weapons and raise the ceiling for warheads on its fleet of submarine-based ballistic missiles. The reaction from Scotland, where Britain’s weapons are based, and elsewhere was swift and harsh.

Scottish National Party defence spokesman Stewart McDonald said:

"It speaks volumes of the Tory government's spending priorities that it is intent on increasing its collection of weapons of mass destruction - which will sit and gather dust unless the UK has plans to indiscriminately wipe out entire populations - rather than address the serious challenges and inequalities in our society that have been further exposed by the pandemic."

That critique echoes the arguments of anti-nuclear, anti-colonialist leaders of an earlier era of nuclear disarmament and human rights campaigning.

That critique echoes the arguments of anti-nuclear, anti-colonialist leaders of an earlier era of nuclear disarmament and human rights campaigning.

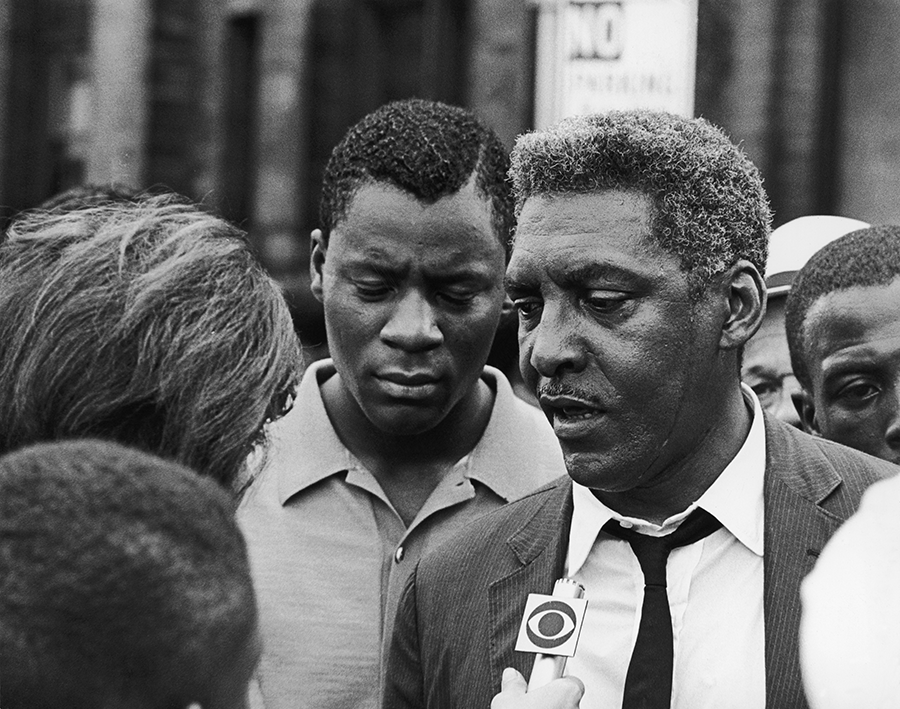

In 1959, Bayard Rustin, one of the most important organizers of the Civil Rights Movement, took part in a historic Easter weekend march from London to Aldermaston, the location of a key British nuclear weapons facility. As thousands gathered in Trafalgar Square, Rustin approached the microphone and said:

“There must be unilateral disarmament action by a single nation, come what may. There must be no strings attached. We must be prepared to absorb the danger. We must use our bodies in direct action, non-cooperation, whatever is required to bring our government to its senses. In the United States, the Black people of Montgomery said, ‘We will not cooperate with discrimination.’ And the action of those people achieved tremendous results. They are not riding buses with dignity, because they were prepared to make a sacrifice of walking for their rights.”

Anti-nuclear activist Michael Randle recalled, “Bayard Rustin delivered what many regarded as the most powerful speech of that Good Friday afternoon, linking the struggle against weapons of mass destruction with the struggle for Blacks for their basic rights in America.”

Bayard Rustin, born on this day in 1912, began his journey into peace activism in the 1930s. As one of Congress of Racial Equality’s (Congress for Racial Equality) first field organizers, Rustin routinely worked with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, War Resisters League, and Committee for Non-Violent Action on nuclear issues, including the “Fast for Peace,” and the “Caravan for Peace.”

However, Rustin believed they needed to go further. When the United States began the development of the hydrogen bomb, Rustin suggested to fellow peace activists that they should “travel to Los Alamos to obstruct the coming in of materials” or renounce their citizenship to raise awareness. Rustin believed such dramatic action would show people “the price he was willing to pay” to abolish nuclear weapons. Few in the peace movement, however, could stomach Rustin’s radical approach to nuclear disarmament.

For Rustin, who worked in both the civil rights and nuclear disarmament movements, these issues were inextricably linked. This became clear in the summer of 1959 when French leaders in Paris decided to test their first nuclear weapon in Algeria, which was under French rule at the time. Many Africans saw the test as an unacceptable form of nuclear colonialism. Those who lived as far away as Ghana feared that the nuclear fallout would devastate their cocoa industry.

Hearing the news, Rustin organized a team of activists and headed to the Sahara to stop the nuclear test. Literally putting their bodies on the line, the activists tried repeatedly to stop the French test but to no avail. However, looking back on all of his activism throughout his life, Rustin concluded that the Sahara protest was “the most significant non-violent project” in which he had participated.

It remains tragic that so many still have never heard of Bayard Rustin. As a gay man, Rustin was often marginalized and forced into the background, even though he was one of the best organizers the movement ever had.

Today, as we mark Rustin’s birthday, the struggle to free ourselves from the dangers of nuclear weapons and to address the health and environmental damage from nuclear weapons production and testing continues.

As the news about the United Kingdom decision to increase its nuclear warhead stockpile breaks, there are also new reports documenting that France greatly underestimated the deadly effects of the radioactive fallout from some of its largest atmospheric nuclear test explosions in the Pacific Ocean in the 1960s and 1970s, which have led to increased cancer incidence in Tahiti and nearby islands.

And even today, there are still traces of the 1960s nuclear tests in the Sahara in the sand particles that are kicked up by the winds over the former French test site in Algeria. Last month, scientists detected a spike in radioactivity when a dust storm kicked up radioactive particles and send them hundreds of miles away, including over parts of France, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Ireland.

Rustin knew that racism and nuclear weapons were part of the same problem and his activism reflected that reality. If Rustin were still alive today there is little doubt that he would be organizing with anti-nuclear weapons and Black Lives Matter activists. For Rustin, this was the path to a more just and equal world, and–I would argue—that remains true today.