By Greg Thielmann

The latest semi-annual exchange of data under the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) shows continuing U.S. lethargy in implementing the modest reductions agreed to when it joined Russia in signing the treaty three-and-a-half years ago.

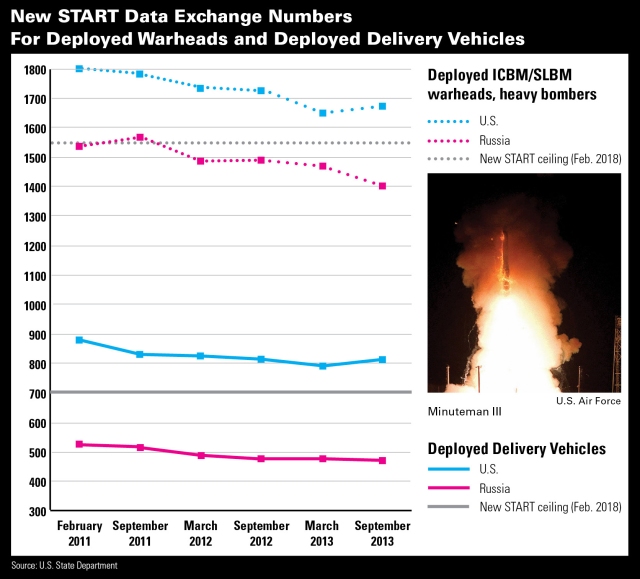

One should not over-read any change from one period to the next. Numerical spikes or dips can occur from such things as ballistic missile submarines entering or leaving overhaul or from already retired weapons finally being destroyed under the terms of the treaty and taken off the official rolls. Yet a clear picture of trends emerges after connecting the dots from the six data exchanges that have occurred since New START reporting began in 2011.

Although the parties are not obligated to reach the treaty limits until February 2018, Russia is already significantly below the limit for deployed strategic warheads (1,550) and deployed strategic launchers (700), while the United States remains significantly above each.

The New START data released by the State Department on Oct. 1 shows the United States currently deploys 1,688 strategic warheads; Russia deploys 1,400 strategic warheads. The growing gap of nearly 300 deployed strategic warheads between the two countries is now larger than the entire nuclear arsenal of any third country. Currently, the United States has 809 ICBMs, deployed SLBMs, and deployed Heavy Bombers, while Russia deploys 473.

Contrary to the alternative reality preached by arms control skeptics such as Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Ala.), who says that President Obama's "priority appears to be tearing down our nuclear deterrent," U.S. deployed forces today remain well-above New START limits while Russia's are going lower.

Missed Nuclear Risk Reduction Opportunities

While New START provides precise and reliable measurements of Russia's strategic forces and high confidence that those forces will not exceed certain limits throughout the rest of this decade, the trends documented in the New START data exchanges from 2011-2013 reveal serious shortcomings in the Obama administration's pursuit of its goal of reducing the number of excess, Cold War weapons and putting pressure on other states to do their part for nuclear nonproliferation.

First, it has become clear that the United States is failing to exploit the opportunity to help induce Russia to continue downsizing its strategic force levels by moving more expeditiously toward the New START limits in the treaty that both have already ratified.

The latest reported U.S. strategic force levels also suggest that the new nuclear weapons policy implementation guidance Washington finally announced in June 2013 has not yet had much of an impact on forces in the field.

In June, President Obama announced that he had determined, and his senior military leadership had agreed, that the United States can safely pursue up to a one-third reduction in deployed strategic nuclear weapons below New START levels. With the gap between U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear weapons now at almost , there is no reason to delay the start of that process.

It is in America's interest to accelerate the pace of New START reductions and to pursue further reciprocal nuclear reductions in parallel with Russia. Because of the obsolescence of Cold War systems in Russia's aging arsenal and the impoverishment of strategic development efforts there in the 1990s, Russia's numbers are bound to continue their decline for some time before the trend can be reversed.

But if the United States continues to slow-roll implementation of New START, Russian planners must not only take into consideration the growing warhead gap in deployed forces, but also the gap in deployed delivery vehicles, which means that Russia's smaller number of missiles and bombers make it theoretically more vulnerable to a first-strike attack. Moreover, the larger number of U.S. spare warheads and the greater upload capability of its missiles mean that Russia may continue to fear that the United States has a greater capacity for breaking out of treaty constraints.

Rather than induce Russia to build up its forces to New START levels, the United States should seek to convince Moscow to pursue further negotiated reductions by accelerating the pace of its own planned reductions and signal that it is prepared to reduce strategic nuclear stockpiles even further.

Nonproliferation is another reason why it is in America's interest to get down to New START limits ahead of schedule. The slow pace of U.S. implementation of its New START arms reduction obligations encumbers U.S. efforts to slow or halt the spread of nuclear weapons to other countries, including our early efforts to persuade China to freeze its nuclear forces and engage seriously in nuclear arms control.

Many non-nuclear-weapons states already chafe under the discriminatory nature of a nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty that legitimizes the nuclear weapons of five states. Any perception that these states are dragging their feet to fulfill their nuclear disarmament obligations in Article VI of the treaty damages prospects for strengthening the implementation and enforcement of the treaty's other provisions.

U.S. policy should seek to convince Moscow that negotiated limits rather than a military build-up would provide the most desirable means of achieving Russia's security. But at the very time when an accelerated U.S. reduction schedule could help convince Moscow that it might not need to develop and deploy a large ICBM with many nuclear warheads, or that Russia will not be threatened by the ever expanding strategic ballistic missile defense system of the United States, the flat-lining of U.S. warhead reductions is likely to do just the opposite.

If the U.S. trend lines revealed by New START data exchanges do not start moving in the right direction soon and the gap between U.S. and Russian weapons does not stop growing, the opportunity for taking the next step in nuclear arms control may just disappear over the horizon.