“For half a century, ACA has been providing the world … with advocacy, analysis, and awareness on some of the most critical topics of international peace and security, including on how to achieve our common, shared goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.”

Congress Must Expand Support for Downwinders

October 2024

By Daryl G. Kimball

Nearly 80 years have passed since the atomic bomb created by J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project was detonated secretly in central New Mexico. The Trinity explosion not only ushered in the nuclear age and triggered the Cold War arms race, it also spread deadly radioactive fallout across dozens of states and led to increased rates of cancer and other radiation-related illnesses for millions of American downwinders.

The United States went on to test 928 nuclear bombs at the Nevada Test Site outside Las Vegas, 100 of which were above ground. Most of these blasts were far more powerful than the bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In addition, hundreds of thousands of uranium miners, workers who manufactured weapons, and residents of communities in dozens of states were poisoned by the wastes produced by the Manhattan Project and the massive weapons complex that was part of the nuclear arms buildup that followed World War II.

Today, thousands of Americans still live with the tragic consequences of Oppenheimer’s bomb and the orgy of nuclear testing and weapons production that followed. For them, the Cold War has never really ended.

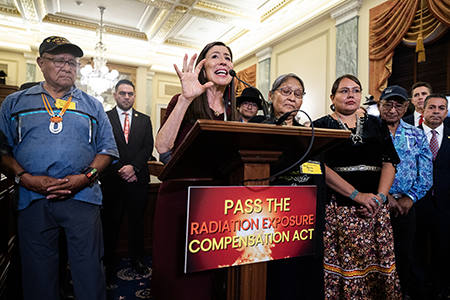

Unfortunately, the leadership in the House of Representatives has blocked legislation that would reauthorize and expand a program under the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) to assist those harmed by Cold War-era uranium mining, nuclear weapons production, and testing.

Before adjourning this year, House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) and Congress have an opportunity and a moral obligation to approve updated legislation that would begin to address the shortcomings of the original RECA program, which excluded far too many victims of the U.S. testing program.

The existing program provides limited compensation only to those who lived in 22 largely rural counties of Arizona, Nevada, and Utah between 1951 and 1958 and during the summer of 1962 who developed leukemia or one of 17 other kinds of cancer. It also covers uranium miners from 1942 through 1971 who can document a subsequent diagnosis of a specified compensable disease.

The new bill, the Radiation Exposure Compensation Reauthorization Act, introduced by Sens. Ben Ray Lujan (D-N.M.), Mike Crapo (R-Idaho), and Josh Hawley (R-Mo.), was approved by the Senate 69-30. It would reauthorize the RECA program for six years and expand partial compensation to communities that have been excluded. If considered by the House, the bill very likely would win passage. President Joe Biden has said he would sign it.

The RECA program expired in June. Further dithering would be a dereliction of duty. Johnson reportedly has complained that the Senate bill would cost tens of billions of dollars and compensate people who were not affected by nuclear testing and Manhattan Project-era weapons production.

He is wrong on both counts. As of February 2024, the RECA program had paid $2.6 billion to more than 41,000 claimants since the program began in 1990. Experts say that if the program were reauthorized for six years and expanded, it is highly unlikely that there would be more than $5 billion in additional eligible claims, if that much.

In any case, the additional money spent on an expanded RECA program would amount to a small fraction of the estimated $756 billion that the United States expects to pay for modernizing its massive nuclear arsenal over the coming decade.

Cost should not be an issue. But if House leaders truly are concerned about that factor, they could work with RECA proponents in both chambers to set a cap on the total amount that could be paid for compensation claims.

Moreover, numerous health studies since 1990 have shown that fallout from past nuclear tests did not stop at the county or state lines recognized under the original RECA program. For instance, northern Utah, the most populated area of the state, never has been included in the program.

Incredibly, the many downwinders affected by the Trinity test in New Mexico, who are mostly Hispanics and Native Americans, never were warned about the fallout, never were acknowledged as victims, and never were included in the RECA program. Uranium miners working after 1971 and communities in the Navajo Nation and other western states whose land and water is still poisoned by uranium mining waste have been ignored as well. So have residents whose homes and schools are contaminated by radioactive waste from Manhattan Project-era sites around St. Louis and other former weapons-related sites across the country, including my hometown of Oxford, Ohio.

Under the Senate bill, the RECA program would be extended to eligible downwinders in seven western states and Guam. It also would add additional uranium workers and residents in Alaska, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee who are living in or near areas contaminated by the effects of nuclear weapons production.

Americans who have been endangered by their government’s nuclear weapons production and testing without their knowledge or consent deserve justice and accountability.

A version of this op-ed, co-authored with Mary Dickson, first appeared in The Hill in June.