Japan, U.S. Bolster Extended Deterrence

September 2024

By Shizuka Kuramitsu

Japan and the United States have reaffirmed and expanded their commitments to maintain peace and security in the Indo-Pacific region, where extended deterrence is becoming a significant component of alliance and regional cooperation.

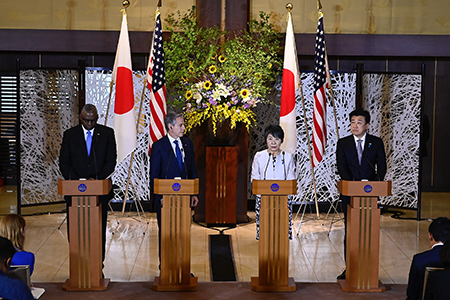

At the Japan-U.S. Security Consultative Committee meeting, known informally as 2+2, on July 28 in Tokyo, Japanese Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa and Defense Minister Minoru Kihara held talks with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin on regional security in Asia and on Japanese-U.S. alliance cooperation. The last such meeting was in Washington in January 2023.

According to a joint statement, the officials “reaffirmed their intent to implement new strategic initiatives…including upgrading alliance command and control, deepening defense industry and advanced technology cooperation, and enhancing cross-domain operations.”

During a joint press conference, Austin emphasized that the upgrade of the “U.S. Forces Japan to a Joint Force Headquarters with expanded missions and operational responsibilities…will be the most significant change to [the command] since its creation and one of the strongest improvements in our military ties with Japan in 70 years.”

Following the 2+2 meeting, which focuses on alliance security cooperation generally, the four officials attended the first Japanese-U.S. ministerial meeting dedicated specifically to deterrence. In those talks, the officials focused on the U.S. commitment under the 1960 U.S.-Japan Security Treaty to extend deterrence to Japan by guaranteeing the use of U.S. military capabilities, including nuclear forces, to counter enemy threats. The credibility of these assurances is a central issue in alliance policy, especially given rising regional tensions.

The United States and another extended deterrence partner, South Korea, already upgraded their consultative body, the Nuclear Consultative Group, which issued guidelines earlier in July.

Japan and the United States have conducted the extended deterrence dialogue at the working level since 2010. Although that format will continue as a primary platform, Kihara emphasized the importance of the new ministerial initiative, stating that, “[i]n view of the severe security environment, including nuclear, it was extremely meaningful that the first ministerial meeting dedicated [solely] to extended deterrence was held [and] where intensive discussions took place.”

In a second joint statement, the officials said that they “shared assessments of an increasingly deteriorating regional security environment” related to China, North Korea, and Russia. As a result, “the United States and Japan reiterated the need to reinforce the alliance’s deterrence posture, and manage existing and emerging strategic threats through deterrence, arms control, risk reduction, and nonproliferation.”

The officials also reaffirmed their “commitment to close consultations on U.S. nuclear policy and posture, as well as the relationship between nuclear and non-nuclear military matters within the [a]lliance.”

“Our commitment to Japan’s defense is unwavering, and that includes extended deterrence by providing the full range of our conventional and nuclear capabilities. This commitment is at the heart of the U.S.-Japan alliance, and our alliance has never been stronger,” Austin said.

The meetings followed Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s official visit to Washington in April and are aimed at realizing a “free and open” Indo-Pacific region.

Japan is increasing its reliance on U.S. extended deterrence, but worldwide nuclear disarmament remains a national goal.

Speaking in Hiroshima on Aug. 6, the anniversary of the U.S. atomic bombing of that city, Kishida noted that “[t]he widening division within the international community over approaches to nuclear disarmament, Russia’s nuclear threat, and other concerns make the situation surrounding nuclear disarmament all the more challenging.”

But “no matter how arduous this path towards a world without nuclear weapons may be, we must continue moving forward along that path,” he said.

Kishida, who represents Hiroshima’s 1st legislative district, has a reputation for a strong political interest in nuclear disarmament. He recently announced that he would not run for the upcoming party leadership vote in September, meaning that Japan is expected to have new prime minister later that month. Before he steps down, he plans a last trip to the UN headquarters in New York.