The 1970s ICBM ‘Window of Vulnerability’ Still Lingers

September 2024

By Frank N. von Hippel

During the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, the technological nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union was fast, furious, and frightening.

The United States realized it was in a competition when it detected the first Soviet nuclear test in 1949, sooner than almost all predictions. That test triggered a race for the much more powerful thermonuclear bombs that were tested by both countries a half-decade later.

For nuclear delivery vehicles, the United States focused initially on transitioning from the World War II propeller-driven bomber to a jet-powered long-range version. The Soviet Union focused more on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), building on the V-2 ballistic missile technology developed by Nazi Germany during World War II.

The U.S. ICBM program was launched 70 years ago, on August 5, 1954, when the U.S. Air Force top secret Western Development Division started work on the goal of delivering a fully operational weapon system to the Strategic Air Command within six years. U.S. ICBMs were initially liquid fueled but later solid fueled, enabling low maintenance and constant launch readiness. A decade after Sputnik’s flight, the United States had 1,000 solid-fueled Minuteman ICBMs sheltered in underground silos in the Great Plains, plus 656 shorter-range submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), also solid fueled, on 41 ballistic missile submarines.1

Simultaneously, both countries began to develop ballistic missile defense systems. They then deployed multiple warheads on their ballistic missiles to assure that they could overwhelm any large-scale defenses. Despite the fact that the Soviet Union and the United States agreed in 1972 to limit themselves to 100 interceptor missiles each, by the end of the Cold War, they each had deployed about 10,000 offensive strategic ballistic missile warheads.

Today, Russia and the United States have reduced their arsenals to about 1,500 deployed strategic ballistic missile warheads each, still enough to destroy civilization many times over. Yet, in July, the Senate Armed Services Committee added to its version of the annual National Defense Authorization Act a requirement for an “assessment of [an] updated force sizing requirement” and for the Pentagon to submit to Congress “a strategy that enables the United States to concurrently...achieve the nuclear employment objectives of the President against any adversary that conducts a strategic attack against the United States or its allies [and] hold[s] at risk all classes of adversary targets [in China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia] described in the nuclear weapons employment guidance issued by the President.”2

The ‘Window of Vulnerability’

The short flight times of strategic ballistic missiles—30 minutes for ICBMs and half that for SLBMs—have long inspired nightmares about the possibility of Pearl Harbor-type surprise attacks. Albert Wohlstetter’s 1958 article, “The Delicate Balance of Terror,” published the year after Sputnik’s flight, provoked a large amount of literature on this subject.3

During the 1970s, the possibility that Soviet ICBMs could become accurate enough (within about 1,000 feet)4 to destroy missile silos hardened to survive a blast overpressure of 2,000 pounds per square inch became one of the founding issues for the Committee on the Present Danger, which was established in 1976 by a group of leading U.S. nuclear hawks. The committee did not accept the intelligence community’s assessment of the accuracy of Soviet ICBMs and pressed the Ford administration for an independent review by committee experts. President Gerald Ford’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board supported the proposal, and the CIA agreed to allow a “Team B” assessment of its intelligence. That assessment erred in the direction of worst-case estimates of Soviet missile accuracy, resulting in subsequent CIA estimates being similarly skewed.5 Committee members filled top security posts in the Reagan administration and pushed for a buildup of similar capabilities.

Later, it was learned from the archive of Vitalii Kataev, the top nuclear expert in the Soviet Central Committee, that Soviet ICBMs still had not achieved an accuracy sufficient to realize the feared “window of vulnerability” for U.S. ICBM silos as of 1991, when the Soviet Union disintegrated.6 U.S. ballistic missile accuracy, however, improved more rapidly. With deployment of the 10-warhead MX ICBM and eight-warhead Trident II SLBM in 1986 and 1990, respectively, the United States created a window of vulnerability for Soviet/Russian and Chinese silo-based ICBMs.7 Those countries responded by deploying significant fractions of their ICBMs on mobile launchers.

The Pentagon also decided on mobile basing for 200 MX ICBMs on massive transporters that would shuttle the missiles between 5,000 missile shelters on 8,000 miles of special heavy-duty roads in a manner designed to make it impossible for the Soviets to determine which shelters contained the missiles.8 This proposal was rejected by candidate base states Nevada and Utah. With the Cold War winding down, the Pentagon simply deployed 50 MX missiles in Minuteman silos and adopted on an “interim” basis a “launch under attack” posture for all of its silo-based ICBMs, which is still in effect 50 years later.

Launch Under Attack

The primary advantage of a launch-under-attack posture is its low cost. Its major disadvantage is the danger of accidental launch. In 1979, National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski’s military assistant argued that U.S. early-warning systems were “just not good enough to let us know that our ICBMs are under attack” and that a launch-on-warning posture would be futile in any case because U.S. ICBMs would be targeted on “empty Soviet silos.” He pressed Brzezinski to call on Secretary of Defense Harold Brown “to withdraw the [launch-under-attack] option.”9

Nevertheless, today, the launch-under-attack posture remains for Minuteman III ICBMs and for their proposed silo-based successors, the Sentinel ICBMs, which are planned for deployment starting around 2030.

Despite the “dual phenomenology” requirement that indications of a possible missile attack detected by satellites be confirmed by early-warning radars, command-and-control expert Bruce Blair reported that,

in the two scariest episodes [of false warning], early[-]warning crews cancelled the alarms after eight minutes...a delay over the requisite three minutes designated in the launch-on-warning protocol that was deemed so egregious that it got them fired on the spot….

[C]yber warfare is compounding these risks. Cyber penetration of early[-]warning networks could corrupt the data on which a presidential launch decision would depend…. [T]he requirement for bug-free nuclear command, control and communication is officially waived in order to provide the president with prompt launch options.10

As frightening as the possibility of an accidental launch is the scenario for an end-of-civilization spasm that the Pentagon’s launch-under-attack posture sets up. In a 1998 interview, General George Lee Butler, the first commander of Strategic Command (1992-1994), warned that Strategic Command had become obsessed by its requirement for

exact destruction of 80 percent of the adversary’s nuclear forces, [and when] they realized that they could not in fact assure those levels of damage if the president chose to ride out an attack…[t]hey built a construct that powerfully biased the president’s decision process toward launch before the arrival of the first enemy warhead…. The consequences of deterrence built on a massive arsenal made up of a triad of forces now simply ensured that neither nation would survive the ensuing holocaust.11

U.S. presidents since Ronald Reagan have been terrified by the possibility of being put into the position of having to make a launch-on-warning decision within a few minutes on the basis of uncertain information.12 In 1994, Ashton Carter, assistant secretary of defense for nuclear security, asked that the team working on the Clinton administration’s Nuclear Posture Review consider the elimination of land-based ICBMs. This triggered a revolt in the Joint Staff and a letter of protest that was leaked to the Senate Armed Services Committee. Carter was dressed down by a group of generals and abandoned his effort to change the U.S. strategic posture.13

Carter never returned to the issue, even after he became defense secretary in the Obama administration. Some two decades later, however, William Perry, a defense secretary in the Clinton administration, became a leading advocate of eliminating silo-based ICBMs, which he described as “some of the most dangerous weapons in the world [because they could] trigger an accidental nuclear war.”14

President Barack Obama tried and failed to end the launch-on-warning protocol. Yet, his administration’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review resulted in a decision to reduce from three to one the number of warheads deployed on each Minuteman III ballistic missile in order to “enhance the stability of the nuclear balance by reducing the incentives for either side to strike first.”15 The logic was that, with the reduced loading, it would require on average more than one attacking warhead to destroy each U.S. ICBM warhead. This also would better position a U.S. president to resist pressure to launch on warning. Unfortunately, the Senate Armed Services Committee is pressing the Pentagon today for a “plan for decreasing the time to upload additional warheads” to the ICBM fleet.16

The Biden administration’s 2022 Nuclear Posture Review stated reassuringly that “while the United States maintains the capability to launch nuclear forces under conditions of an ongoing nuclear attack, it does not rely on launch-under-attack policy to ensure a credible response.”17 This would appear to allow the elimination of silo-based ICBMs. It also would allow a leader such as President Joe Biden, who is familiar with the nuclear debate, to resist the pressure that Butler described for a launch-on-warning posture, but not less knowledgeable presidents.

Weak Protections Against False Warnings

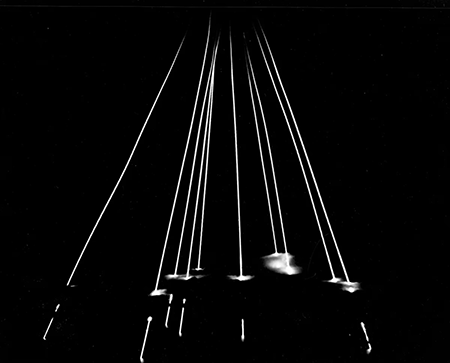

Strategic Command’s insistence on having the option of launching ICBMs before they can be destroyed has been compounded by its concerns about the vulnerability of its nuclear command-and-control system. Therefore, it has built redundancy into the number of ways in which the ICBMs can be launched. Each ICBM can be launched by any of five underground launch-control bunkers or an airborne control post communicating through multiple ground and radio communication links (fig. 1).18

In contrast to this redundancy of positive controls to assure the ICBMs would be launched if ordered, there is not a single system to deal with the possibility of a mistaken or unauthorized launch.

When Minuteman III ICBMs are test-launched with dummy warheads into the Pacific Ocean from Vandenburg Air Force Base on the California coast, they are equipped with command-destruct devices in case a missile veers off course during its powered flight. Each stage of the booster has a linear-shaped charge attached to its side that can be detonated on command to split the stage open so that it loses power and falls into the sea.19

In contrast, ICBMs loaded with nuclear warheads are not equipped with command-destruct devices. They have been excluded because the destruct code might leak and be used by an enemy, even though the probability of that happening could be reduced to an infinitesimal level.20

The ICBM launch-on-warning posture and the lack of a command-destruct system make clear that the Pentagon’s priority is to make sure that nothing can prevent U.S. nuclear missiles from launching. The priority should be that they will not launch until after the determination that a nuclear attack has occurred and a thorough assessment has been made of how the United States should best respond in a way that minimizes the probability of an escalation to nuclear Armageddon.

U.S. silo-based ICBMs are not well matched to that priority, but other legs of the triad could be. U.S. ballistic missile submarines at sea are survivable. In a crisis, bombers could be kept on strip alert so that they could be launched on warning to assure their survival because, unlike ballistic missiles, they can be recalled.21

The United States has lived with its nuclear ICBMs on hair trigger for 50 years. It should end that posture before it runs out of luck.

ENDNOTES

1. U.S. National Park Service, “History of Minuteman Missile Sites,” n.d., https://npshistory.com/publications/mimi/srs/history.htm (accessed August 26, 2024); Robert S. Norris and Thomas B. Cochran, “US-USSR/Russian Strategic Offensive Nuclear Forces: 1945-1996,” Natural Resources Defense Council, January 1997, https://nuke.fas.org/norris/nuc_01009701a_181.pdf.

2. National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025, S. 4638, 118th Cong. (2024), sec. 1514 (hereinafter 2025 NDAA).

3. Albert Wohlstetter, “The Delicate Balance of Terror,” Rand Corp., n.d., https://www.rand.org/pubs/papers/P1472.html.

4. Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan, “The Effects of Nuclear Weapons,” 3rd ed., U.S. Departments of Defense and Energy, 1977, pp. 110-111

5. Anne H. Cahn, Killing Detente: The Right Attacks the CIA (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998).

6. Pavel Podvig, “The Window of Vulnerability That Wasn’t,” International Security, Vol. 33,

No. 1 (2008): 118-138.

7. Donald MacKenzie, Inventing Accuracy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), app. A.

8. Office of Technology Assessment, “MX Missile Basing,” 1981, pp. 60, 65.

9. William E. Odom to Zbigniew Brzezinski, memorandum, October 8, 1979, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/19357-national-security-archive-doc-30-william-e-odom.

10. Bruce G. Blair, “Loose Cannons: The President and U.S. Nuclear Posture,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 1, 2020, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2020-01/loose-cannons-the-president-and-us-nuclear-posture/.

11. Jonathan Schell, The Gift of Time (New York: Henry Holt, 1998), p. 194.

13. Janne E. Nolan, An Elusive Consensus: Nuclear Weapons and American Security After the Cold War (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1999), ch. 3.

14. William J. Perry, “Why It’s Safe to Scrap America’s ICBMs,” The New York Times, September 30, 2016.

15. U.S. Department of Defense, “Nuclear Posture Review Report,” April 2010, p. 23, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/defenseReviews/NPR/2010_Nuclear_Posture_Review_Report.pdf.

17. U.S. Department of Defense, “2022 Nuclear Posture Review,” October 27, 2022,

p. 15, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF#page=51.

18. The Military Standard, “Minuteman Communications Network,” n.d., http://www.themilitarystandard.com/missile/minuteman/communications.php (accessed August 26, 2024).

19. U.S. Department of Defense, “Missile Work,” n.d., https://www.defense.gov/Multimedia/Photos/igphoto/2002067554/ (accessed August 26, 2024); Naval Surface Weapons Center, “Space Shuttle Range Safety Command Destruct System Analysis and Verification: Phase 1 - Destruct System Analysis and Verification,” NSWC/TR 80-417, March 1981, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA103453.pdf.

20. Sherman Frankel, “Aborting Unauthorized Launches of Nuclear-Armed Ballistic Missiles Through Post-Launch Destruction,” Science & Global Security, Vol. 2 (1990), pp. 1-20.

21. See, e.g., Global Zero U.S. Nuclear Policy Commission, “Modernizing U.S. Nuclear Strategy, Force Structure and Posture,” Global Zero, May 2012, https://www.globalzero.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/gz_us_nuclear_policy_commission_report.pdf.

Frank N. von Hippel is a professor of public and international affairs emeritus at Princeton University.