“For half a century, ACA has been providing the world … with advocacy, analysis, and awareness on some of the most critical topics of international peace and security, including on how to achieve our common, shared goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.”

South Korea Walks Back Nuclear Weapons Comments

March 2023

By Kelsey Davenport

South Korea walked back comments from its president suggesting that the country may need to pursue a nuclear deterrent to counter the growing threat posed by North Korea’s advancing weapons program. International backlash to the comments suggests that South Korea would pay a high price if it decided to develop its own nuclear weapons.

President Yoon Suk Yeol told officials in the South Korean Defense and Foreign Affairs ministries on Jan. 11 that if the threat posed by North Korea “gets worse,” it is possible that “our country will introduce tactical nuclear weapons or build them on our own.” He added that if the decision were made to develop nuclear weapons, Seoul could build them “pretty quickly, given our scientific and technological capabilities.”

President Yoon Suk Yeol told officials in the South Korean Defense and Foreign Affairs ministries on Jan. 11 that if the threat posed by North Korea “gets worse,” it is possible that “our country will introduce tactical nuclear weapons or build them on our own.” He added that if the decision were made to develop nuclear weapons, Seoul could build them “pretty quickly, given our scientific and technological capabilities.”

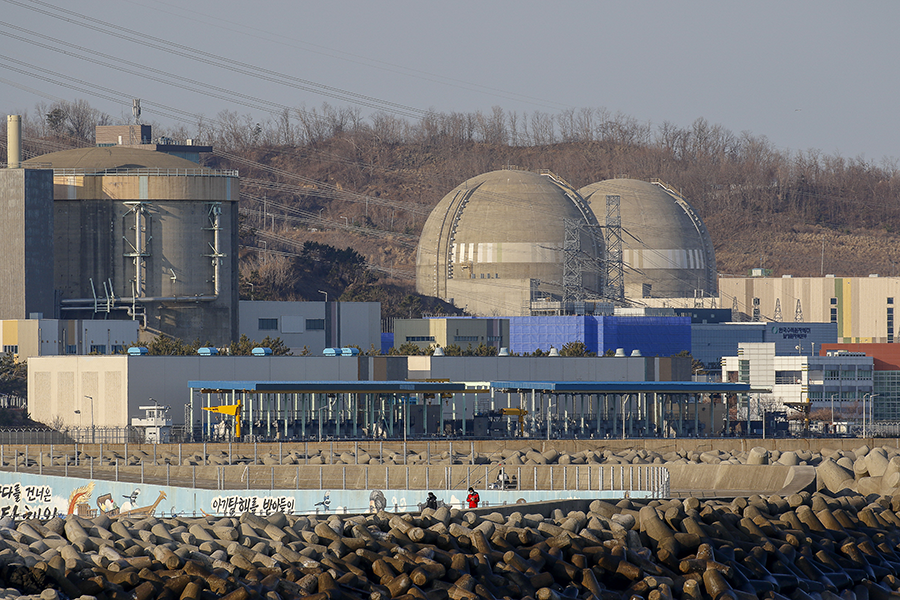

South Korea had a nuclear weapons development program, but gave it up, and in 1975 joined the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), which prohibits states-parties from developing nuclear weapons. After joining the NPT, South Korea built an extensive civil nuclear program and now exports nuclear reactors.

From 1979 to 2000, South Korea conducted experiments with uranium and plutonium that it failed to declare to the International Atomic Energy Agency, as required by its treaty commitments. Seoul said the work was part of its ambitious civil nuclear program and not weapons related. Although its advanced civil nuclear infrastructure would allow Seoul to quickly develop nuclear weapons, it would need to withdraw from the NPT, a move with significant security and economic repercussions.

South Korean officials quickly walked back Yoon’s comments. South Korean Minister of Unification Kwon Young-se said on Jan. 29 that discussing the development of nuclear weapons is “inappropriate” and undermines the long-held goal of denuclearization on the Korean peninsula.

He noted that U.S. nuclear weapons in the region can be used quickly against North Korea if necessary and that South Korea “should not simply think that deploying tactical nuclear weapons on the Korean peninsula will strengthen” its capability to respond to North Korean nuclear weapons.

Yoon also appeared to downplay his remarks, saying in a Jan. 18 interview at the World Economic Forum that Seoul’s “rational option is to fully respect the NPT.”

John Kirby, the U.S. National Security Council spokesperson, rejected the idea that Seoul will develop nuclear weapons. In a Jan. 12 press briefing, he said South Korea has “made clear that they are not seeking nuclear weapons” and reiterated the U.S. commitment to the “complete denuclearization” of the Korean peninsula.

Yoon’s comments reflect a growing South Korean interest in domestic nuclear weapons. Polling data suggest that 70 to 75 percent of the population favors developing such weapons.

But the polls “do not adequately explain to the people the high price South Korea will pay for building nuclear weapons,” a former South Korean official said in a Feb. 13 email to Arms Control Today. South Korea should expect “diplomatic isolation, sanctions, and a rupture in the [South Korean-U.S.] alliance” if it goes down that road, he said.

If Yoon’s comments were intended as a trial balloon for future nuclear weapons development, “the balloon was popped spectacularly,” the former official said, but if they were intended to push the United States to provide South Korea with greater military support, “it might have some success.”

The Biden administration is working closely with Seoul to restore confidence in U.S. defense commitments after President Donald Trump called the alliance into question. Kirby said on Jan. 12 that the United States will seek “improvements in extended deterrence capabilities” jointly with South Korea.

Comments by Yoon earlier in January suggested that his administration is interested in a greater role in U.S. nuclear planning and extended deterrence commitments to South Korea. Although U.S. President Joe Biden said on Jan. 3 that the United States is not participating in joint nuclear exercises with South Korea, South Korean Defense Minister Lee Jong-sup said on Jan. 11 that Washington is willing to "drastically expand” information shared with Seoul and take its views into account. He also said the two allies were planning tabletop exercises for February that are focused on “extended deterrence under the scenario of North Korea’s nuclear attacks.”

After meeting Lee on Jan. 31, U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said that the United States will increase the number of fighter jets, bombers, and other advanced weapons systems deployed in South Korea. Austin and Lee also agreed to expand South Korean-U.S. military exercises and to continue the “timely” deployment of U.S. strategic assets in the region.

Pyongyang responded by saying that the United States is “going to ignite an all-out showdown” with North Korea and that expanding military exercises “will result in turning the Korean peninsula into a huge war arsenal.” It promised to use its “powerful deterrence” to root out the U.S. hostile policy and the military threat posed by the United States and “its vassal forces.”

This is not the first time Yoon raised the prospect of nuclear weapons in South Korea. During his presidential campaign, he suggested that the United States could redeploy tactical nuclear weapons that it removed from South Korea in 1991, but the Biden administration quickly rejected the idea.

Yoon’s comments come amid increasing tensions on the Korean peninsula and a significant expansion in North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. North Korea conducted an unprecedented 69 ballistic missile tests in 2022, and South Korea responded to several of them by launching its own systems. North Korea also flew drones into South Korea in December, prompting the South to respond by sending its own drones into North Korea.

Yoon’s comments come amid increasing tensions on the Korean peninsula and a significant expansion in North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. North Korea conducted an unprecedented 69 ballistic missile tests in 2022, and South Korea responded to several of them by launching its own systems. North Korea also flew drones into South Korea in December, prompting the South to respond by sending its own drones into North Korea.

The expansion of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program appears poised to continue in 2023.

On Feb. 18, North Korea launched an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), which state-run media said was part of the government’s “persistent and strong” plan to counteract South Korean-U.S. military drills. The next day, the United States responded to the test by flying B-1B strategic bombers over the Korean peninsula in coordination with the South Korean air force. The flights prompted North Korea to launch two short-range ballistic missiles on Feb. 20.

Kim Yo Jong, sister of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, said on Feb. 20 that Pyongyang will continue to use the Pacific Ocean as a “shooting range” in response to U.S. military actions in the region.

Kim Jong Un declared in a Jan. 1 speech that Pyongyang plans to increase exponentially its stockpile of nuclear warheads, including the mass production of tactical nuclear weapons, and to develop a new ICBM for a “quick nuclear counterstrike” capability. (See ACT, January/February 2023.) The focus on expanding tactical nuclear weapons, which have a lower yield than strategic nuclear weapons and are more likely to be deployed on shorter-range missiles or artillery, is directed at South Korea in particular.

During a military parade on Feb. 8, North Korea displayed an unprecedented 17 ICBMs, including a mockup of what is likely the new solid-fueled system that Kim said is under development. Solid-fueled systems can be launched more quickly than their liquid-fueled counterparts. North Korea tested a large solid-fueled rocket motor in 2022.

The other ICBM displayed was the Hwasong-17, which is capable of carrying multiple warheads and targeting the entire United States.