“We continue to count on the valuable contributions of the Arms Control Association.”

UN First Committee Calls for ASAT Test Ban

December 2022

By Heather Foye and Gabriela Rosa Hernández

A key UN panel formally adopted for the first time a resolution calling for countries to ban destructive anti-satellite (ASAT) missile tests.

Although not legally binding, the resolution reflects an increase in international political support for prohibiting ASAT weapons testing that destroy objects in space, which is formally referenced as “destructive direct-ascent anti-missile testing.”

Although not legally binding, the resolution reflects an increase in international political support for prohibiting ASAT weapons testing that destroy objects in space, which is formally referenced as “destructive direct-ascent anti-missile testing.”

The vote came during the 77th session of the UN General Assembly First Committee on disarmament and international security as it concluded weeks of negotiations that underscored geopolitical divisions between nuclear-weapon and non-nuclear-weapon states amid Russia’s war on Ukraine.

The ASAT testing resolution was adopted Nov. 1 by a 154–8 vote with 10 abstentions. It was championed by the United States, which is pursuing a related initiative that encourages states to undertake a voluntary moratorium on ASAT testing as a first step to curbing an arms race in space. (See ACT, November 2022.)

Last April, the United States became the first nation to commit to the self-imposed moratorium. Since then, Australia, Canada, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom have followed suit. (See ACT, May 2022.)

According to Reaching Critical Will, some states were displeased that the moratorium contained in the UN resolution was limited and did not restrict the proliferation of other space activities. In opposing the resolution, Belarus, Bolivia, China, Cuba, Iran, Nicaragua, Russia, and Syria noted that the United States already had achieved ASAT missile capability and, hence, the resolution limited real progress toward preventing an arms race in outer space.

India and Pakistan, nuclear-armed states, were among those that abstained from voting on the resolution. Pakistan believed the draft resolution was “piecemeal,” according to Reaching Critical Will, and India is known to have conducted an ASAT weapons test.

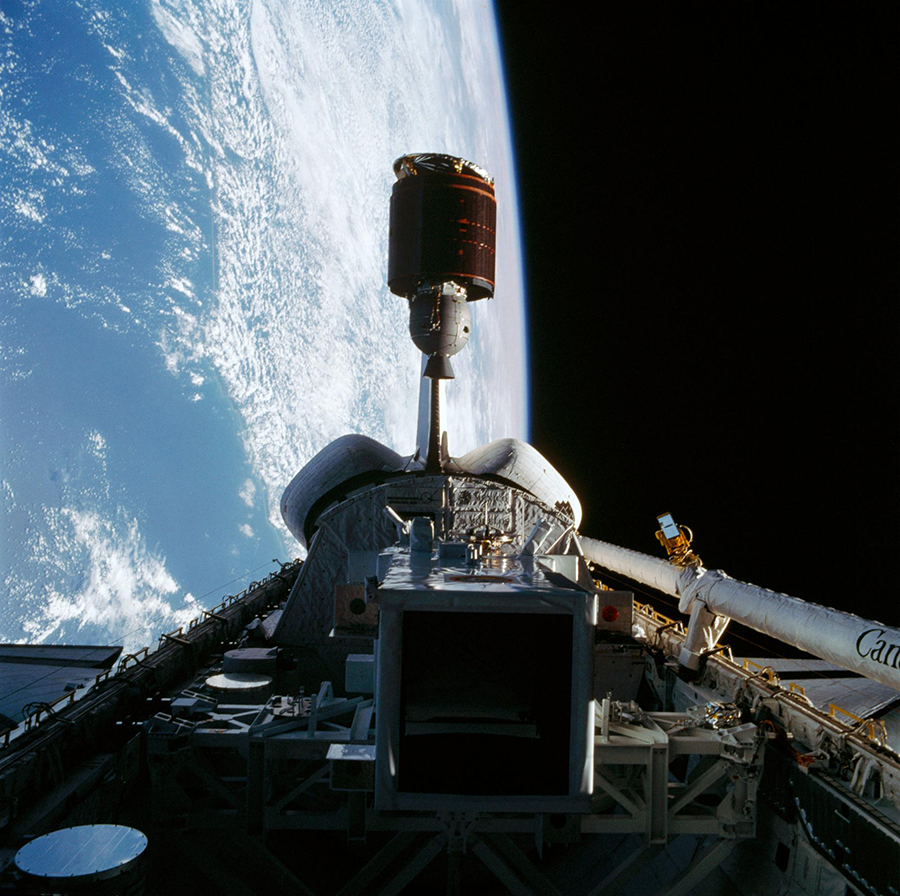

In addition to India and the United States, China and Russia, as well as its predecessor, the Soviet Union, are the only states that have conducted ASAT weapons tests, which typically cause a large quantity of space debris when the missiles ram into orbiting satellites.

Most nations do not possess the technological capability to conduct such missile tests. The resolution builds on progress made last year when the First Committee voted to create an open-ended working group aimed at preventing an arms race in space. (See ACT, December 2021.)

The United States launched its ASAT testing ban initiative following a Russian test in November 2021 that destroyed a Russian satellite that had been in orbit since 1982. The collision caused at least 1,500 trackable pieces of debris to litter space. Astronauts on the International Space Station were advised to take shelter when the station encountered the debris. (See ACT, December 2021.)

Tensions among states at the First Committee also resurfaced over a resolution, introduced annually, on the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). The Oct. 6 resolution called on states to adopt the TPNW and commit not to participate in nuclear weapons activities. The treaty entered into force last year and now has 91 signatory states, 68 of whom have ratified it.

The nine states believed to possess nuclear weapons (China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, the UK, and the United States) again voted against the resolution.

For the first time, Australia, which is under the U.S. nuclear security umbrella, abstained from voting on the resolution. In previous years dating back to 2018, Australia voted against the resolution. The previous Australian government, led by the Liberal Party, had opposed the TPNW. But the current Labor-led government, which came to power earlier this year, has been more open to embracing it. In June, Australia participated as an observer at the first meeting of TPNW state-parties held in Vienna. (See ACT, July/August 2022.)

Australia is “assessing its position on the TPNW, taking account of the need to ensure an effective verification and enforcement architecture, interaction of the [nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty], and achieving universal support,” the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said in an Oct. 26 statement. It added that the government’s decision to observe the first meeting of TPNW states-parties in June “demonstrates the constructive engagement with the treaty.”

One month earlier, Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong pointed to the “weak and desperate” nuclear rhetoric of Russian President Vladimir Putin for why Australia would “redouble” its efforts to strengthen the nonproliferation regime. (See ACT, November 2022.)

Australia’s abstention on the TPNW resolution drew a U.S. warning on Nov. 8 when the U.S. Embassy in Canberra said the treaty “would not allow for U.S. extended deterrence relationships, which are still necessary for international peace and security,” The Guardian reported. Finland and Sweden, which applied for NATO membership this year, voted against the TPNW resolution for the first time. (See ACT, November 2022.) Since 2018, both countries have abstained on the resolution. They also attended the TPNW meeting of states-parties as observers.