“We continue to count on the valuable contributions of the Arms Control Association.”

Ukrainian Nuclear Plants Come Under Russian Fire

April 2022

By Shannon Bugos

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has raised the risks of nuclear catastrophe after Russian forces took control of the Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plants, causing fires at both sites. Ukraine said it regained control of Chernobyl on March 31 when the Russians left.

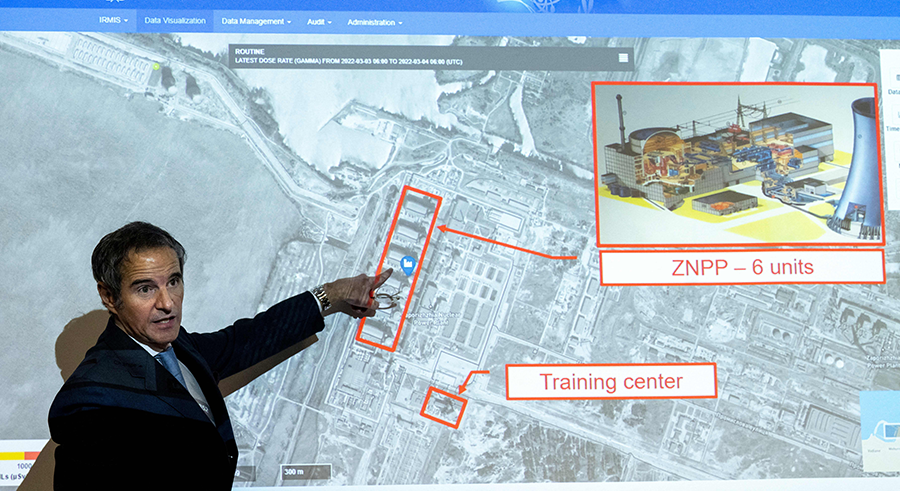

A projectile launched by Russian troops caused a fire at a training complex on the Zaporizhzhya site, Europe’s largest nuclear power plant, on March 4, although the flames were later extinguished. A Russian shell also hit one of the reactors, but the thick walls of the reactor’s containment structure absorbed the strike. The plant houses six of Ukraine’s 15 reactors, which are split among four active nuclear plant sites. Together they supply about half of the country’s electricity.

A projectile launched by Russian troops caused a fire at a training complex on the Zaporizhzhya site, Europe’s largest nuclear power plant, on March 4, although the flames were later extinguished. A Russian shell also hit one of the reactors, but the thick walls of the reactor’s containment structure absorbed the strike. The plant houses six of Ukraine’s 15 reactors, which are split among four active nuclear plant sites. Together they supply about half of the country’s electricity.

“Firing shells in the area of a nuclear power plant violates the fundamental principle that the physical integrity of nuclear facilities must be maintained and kept safe at all times,” said International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi.

During an emergency UN Security Council meeting on March 4, Russian Ambassador Vasily Nebenzya denied his government was to blame. “A massive anti-Russia information campaign is unfolding,” he said, arguing instead that Ukrainian forces attacked Russian forces patrolling outside the plant and set the training building on fire as they departed.

U.S. Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield criticized Russia’s attack on the nuclear power plant as “incredibly reckless and dangerous.” She said that “[n]uclear facilities cannot become part of this conflict.”

In a March 4 blog post, Ed Lyman, director of nuclear power safety at the Union of Concerned Scientists, explained that “[n]one of the reactors were built to withstand a military assault.” Ukraine’s nuclear power plants are also “vulnerable to indirect fire that could damage critical support systems and surrounding infrastructure, potentially resulting in a fuel meltdown and a radiological release that could contaminate thousands of square miles of terrain,” he wrote.

The IAEA reported on March 6 that a Russian commander took control of site management at Zaporizhzhya, including actions related to technical operations, and that Russian forces switched off some mobile networks and internet access, interrupting communications between the staff and Ukraine’s nuclear regulatory agency. This agency, known as the State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine (SNRI), has been providing the IAEA with status updates.

“Employees of the station are under strong psychological pressure from the occupiers,” said Energoatom, Ukraine’s state nuclear company, on March 11. “All staff on arrival at the station are carefully checked by armed terrorists.”

The IAEA reported on March 6 that the technical teams had begun to rotate in three eight-hour shifts.

The dangerous challenges facing the personnel at Zaporizhzhya mirror those at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, which has been under Russian control since Feb. 24.

After 25 days of working nonstop, more than 200 staff members at Chernobyl were finally allowed to change shifts and return home, with half leaving on March 20 and the rest a day later. But 13 staffers declined to rotate, and most Ukrainian guards remained as well, according to Ukrainian officials.

The Chernobyl staff deserves “our full respect and admiration for having worked in these extremely difficult circumstances,” Grossi said on March 20. “They were there for far too long.” A nuclear reactor exploded at Chernobyl in 1986, leading to the eventual closure of the plant’s reactors. The nuclear power plant, located inside a large exclusion zone, is no longer active.

For nearly 600 hours while held at gunpoint by Russian forces, the facility’s staff in charge of safeguarding spent nuclear fuel and radioactive waste grabbed sleep when possible at their workstations, survived on a severely diminished diet, and had their phones confiscated, according to a March 15 report by The Wall Street Journal, which managed to talk to some workers stuck inside.

Some maintenance and repairs could not be completed at Chernobyl due to “the psychological, moral, and physical fatigue of the personnel,” the SNRI said on March 19.

Earlier in the month, Russian forces also twice damaged the facility’s power line, cutting the plant off from Ukraine’s power grid and jeopardizing the cooling systems for the spent nuclear fuel rods. Kyiv also reported on March 22 that Russian troops have destroyed a laboratory that processed radioactive waste and carried out other “strategic, unique functions.”

Further compounding the radiation concerns at Chernobyl has been the breakout of multiple seasonal fires around the site. Russian forces controlling the plant have stymied efforts by Ukrainian officials and firefighters to put out the flames.

Grossi began separate consultations with the Ukrainian and Russian foreign ministers on March 10 in Turkey to establish a framework for ensuring the safety and security of Ukraine’s nuclear facilities. The potential deal will make “no political references to the situation in the plants or no connection that could be construed as legitimizing the presence of anybody in a foreign territory,” he said on March 21, adding that he hopes to reach agreement “very soon.”

The chairs of the U.S. congressional nuclear weapons and arms control working group—Sens. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) and Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) and Reps. Don Beyer (D-Va.) and John Garamendi (D-Calif.)—sent a letter to U.S. President Joe Biden on March 14 suggesting that “the technical expertise of the [IAEA] should be made available to monitor and advise on the rapidly changing situation on the ground.”

They urged him “to find ways to encourage IAEA’s involvement in monitoring” Ukraine’s nuclear power plants.

Chernobyl is located along Russia’s northern invasion route to Kyiv, which is less than 100 miles south from the plant.