Nuclear Threats and Alerts: Looking at the Cold War Background

April 2022

By William Burr and Jeffrey Kimball

Implicit or explicit nuclear threats have been the default position of states possessing nuclear weapons for decades. Such threats are the essence of deterrence: if you attack, we will destroy your society or your most vital military assets. All the same, making a nuclear threat is unusual and alarming. For that reason, explicit threats and the raising of nuclear alert levels have become rare since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

Chinese nuclear threats against Japan and U.S. President Donald Trump’s “fire and fury” threats to North Korea were shocking. The implied nuclear threats that Russian President Vladimir Putin made to the United States and NATO in March as he pressed his full-scale invasion of Ukraine were also startling. Putin said that anyone who stood in the way of the assault would face consequences “such as you have never seen in your entire history.” A few days later, he put Russian strategic forces on “special combat readiness.” That nuclear threats can be made today is a shock to those who thought the end of the Cold War had made them historical curiosities.

Chinese nuclear threats against Japan and U.S. President Donald Trump’s “fire and fury” threats to North Korea were shocking. The implied nuclear threats that Russian President Vladimir Putin made to the United States and NATO in March as he pressed his full-scale invasion of Ukraine were also startling. Putin said that anyone who stood in the way of the assault would face consequences “such as you have never seen in your entire history.” A few days later, he put Russian strategic forces on “special combat readiness.” That nuclear threats can be made today is a shock to those who thought the end of the Cold War had made them historical curiosities.

The recent brandishing of nuclear threats evokes the Cold War days of the 1950s and early 1960s, when such threats, were the modus operandi of superpower conduct during international crises. Such threats became generally irrelevant during the later years of the Cold War and after. How did that come about?

During the Cold War, the possession of nuclear weapons emboldened some national leaders to make threats that they thought would advance their positions in a crisis by coercing or deterring their adversaries. During the Korean War, as a signal to China and the Soviet Union, U.S. President Harry Truman authorized the deployment of nuclear weapons components to Guam, although he otherwise saw military use of nuclear weapons as virtually “taboo.” Rejecting the idea of proscribed weapons, President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s administration considered nuclear options as integral to crisis diplomacy and military planning.1

One political narrative that acquired near-legendary status was the claim that the Eisenhower administration had broken the Korean War diplomatic logjam by using nuclear threats against China. Although Secretary of State John Foster Dulles sent messages to Moscow and New Delhi in the hope that they would reach Beijing, his threats were vaguely general in nature: the United States could take stronger military action and “extend [the] area [of] conflict.” To this day, it is unclear whether those messages reached Beijing or were understood as nuclear threats. More decisive factors in ending the war were the death of Soviet leader Josef Stalin, the eventual flexibility of Communist negotiators, and the conventional bombing of North Korea by the United States. Nevertheless, Eisenhower and Dulles believed their implicit nuclear threats had made a difference. Vice President Richard Nixon agreed.2

Such threats became more explicit later. During the 1954–1955 crisis in the Taiwan Strait, China bombarded the nearby offshore islands, and the United States came incorrectly to fear that Beijing was planning to attack Taiwan. Mao Zedong and the Chinese leadership miscalculated by not anticipating that the United States would bring nuclear-armed aircraft carriers into the area or that Eisenhower would declare publicly that nuclear weapons could be “used as a bullet or anything else” if war broke out with China. The crisis eventually simmered down, but the Chinese decided they needed their own nuclear weapons for deterrence, while Eisenhower and his associates concluded that threats and deterrence had succeeded.3

The Soviet leadership made its threats explicit during the 1956 Suez crisis when the British, French, and Israelis invaded Egypt in response to the latter’s nationalization of the Suez Canal. The Eisenhower administration opposed the invasion and put the British under enough financial pressure to compel them to back down. The United States also raised the alert level of strategic nuclear and naval forces out of concern that the Soviets might intervene to support Egypt.4 The Soviets responded with crude atomic blackmail. The Communist Party’s first secretary, Nikita Khrushchev, sent a letter to UK Prime Minister Anthony Eden asking “what situation would Britain find itself in, if she were attacked by stronger states possessing all types of modern destructive weapons?” The threat had no impact, however, because London was already calling off the invasion. Yet, Khrushchev came away from the crisis convinced that nuclear threats were effective.5

There were more nuclear alerts in 1958, although threatening language was avoided. A political crisis in Lebanon prompted the United States to send the Marines to stabilize the situation. The U.S. Strategic Air Command (SAC) placed nuclear forces in the United States and at overseas bases on alert to deter possible Soviet intervention. Later that summer, another Taiwan Strait crisis erupted, with Beijing again shelling the offshore islands. Although Washington did not stage a SAC alert in that event, it initiated a major show of force with the deployment of nuclear-armed aircraft carriers.6

The Taiwan Strait crisis possessed dangerous potential, and Eisenhower was determined to avoid using nuclear weapons. He instructed the U.S. military that if a conflict broke out, they could only use conventional weapons first. Eisenhower had moved away from casual references about the use of nuclear weapons and was now viewing them as virtually taboo. He told UK Foreign Secretary Selwyn Lloyd that nuclear weapons could only be used for the “big thing” (general war) because when “you use [them] you cross a completely different line.”7

In 1959 the Pentagon devised the Defense Condition (DEFCON) system as a way to raise military alert levels on a systematic, coordinated basis. In the wake of the crisis over the 1960 U-2 downing, when Khrushchev walked out of the Paris summit in protest, top U.S. officials were concerned the Soviets might move against the United States or its European allies. Thus, Secretary of Defense Thomas Gates raised the DEFCON position from 4 to 3, a higher state of readiness, as a “prudent” move.8

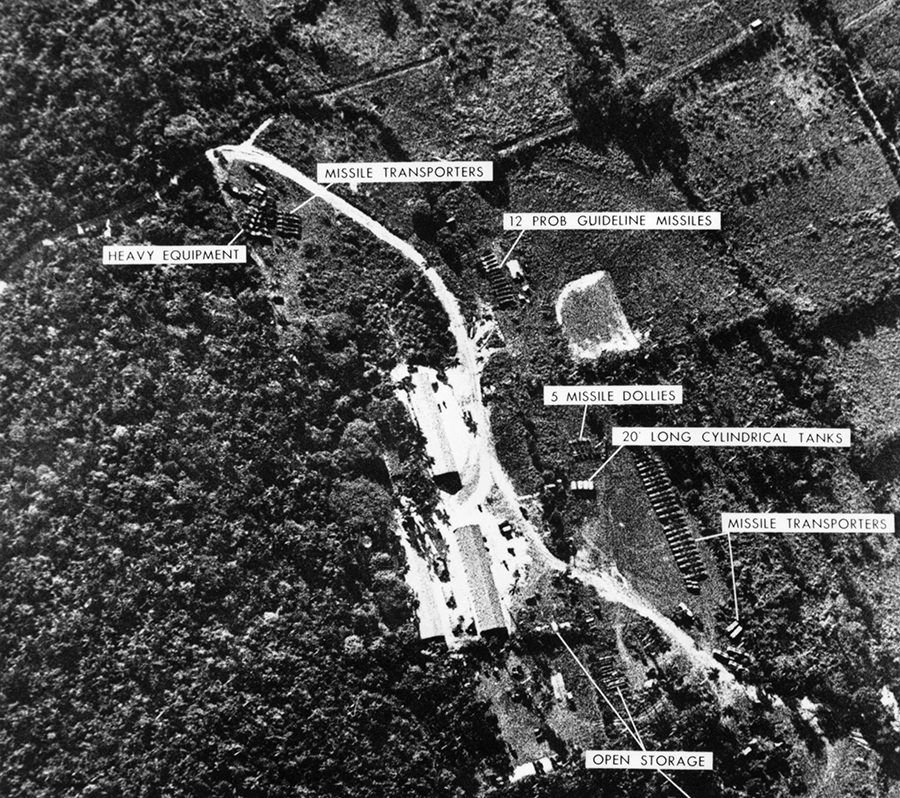

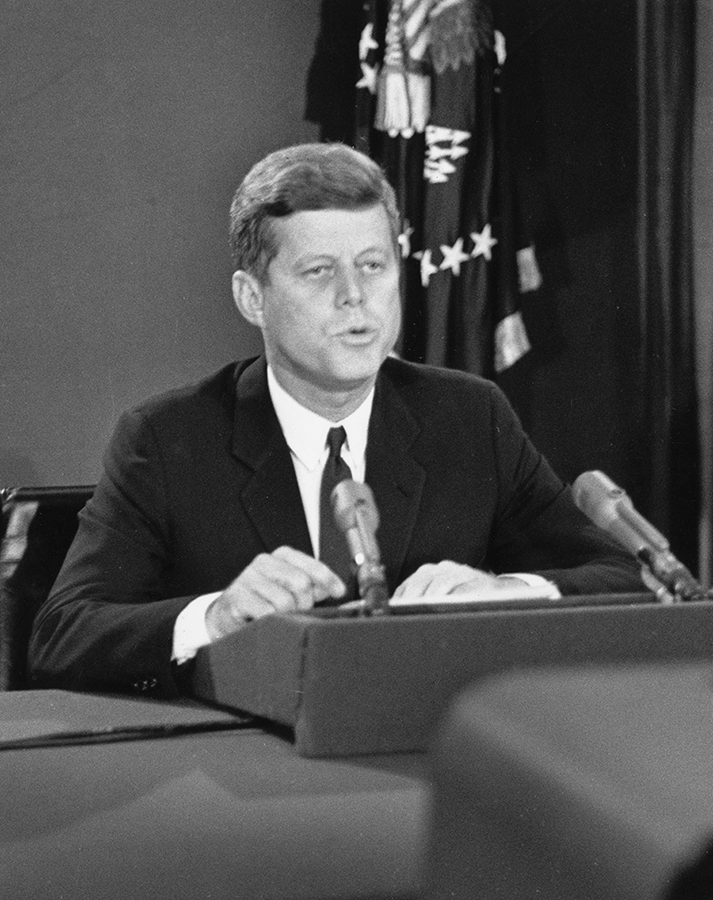

Cuban Missile Crisis

The October 1962 Cuban missile crisis involved the most well-known and dangerous Cold War nuclear alerts and threats. By secretly deploying nuclear-armed intermediate- and medium-range ballistic missiles in Cuba, Khrushchev sought to improve the Soviet strategic position and to use nuclear threats to shield Cuba from another U.S. invasion. After the United States discovered the missiles, the Kennedy administration blockaded Cuba and put U.S. strategic forces on a DEFCON 2 alert, one step away from a general war posture. The Soviets also raised their nuclear alert levels, but not as high as the United States. Neither Kennedy nor Khrushchev wanted war, but miscalculations and accidents could have realized their worst fears, motivating both to reach a settlement, lest the situation spin out of control. The U.S. DEFCON status symbolized the risks of further confrontation.9

Neither side ever raised their nuclear alert systems to such high levels again. The grave dangers of a nuclear crisis made Moscow and Washington more cautious, leading to a period of détente that unfolded in the following years. Nixon, elected president in 1968, pursued détente as an element of Cold War strategy, but threat-making was an important thread in his diplomatic approach. Influenced by his experience during the Eisenhower years and by his observations of Khrushchev, Nixon developed what came to be known as the “Madman Theory,” the notion that threatening excessive or extraordinary force could bring diplomatic gains. National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger later explained that the "president’s strategy has been to ‘push so many chips into the pot’ that the other side will think we might be ‘crazy’ and might really go much further.”10

Neither side ever raised their nuclear alert systems to such high levels again. The grave dangers of a nuclear crisis made Moscow and Washington more cautious, leading to a period of détente that unfolded in the following years. Nixon, elected president in 1968, pursued détente as an element of Cold War strategy, but threat-making was an important thread in his diplomatic approach. Influenced by his experience during the Eisenhower years and by his observations of Khrushchev, Nixon developed what came to be known as the “Madman Theory,” the notion that threatening excessive or extraordinary force could bring diplomatic gains. National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger later explained that the "president’s strategy has been to ‘push so many chips into the pot’ that the other side will think we might be ‘crazy’ and might really go much further.”10

During Nixon’s first year in office, as he tried to settle his biggest political problem, the Vietnam War, he made various low-level threats and feints to warn of the risks of escalation in an effort to coerce North Vietnam to be more yielding in the peace talks. As tough-minded as Nixon thought he was, he saw nuclear weapons as militarily unusable in the Vietnam context. What he especially wanted from threats was to prompt the Soviet Union to motivate its North Vietnamese clients to be more cooperative. He and Kissinger deeply overestimated Moscow’s clout with Hanoi, and none of the threats worked, making Nixon angry. To force Hanoi to make concessions, Nixon had plans to escalate the war in October 1969, but called them off because of the risks that escalation would spark U.S. domestic upheaval.11

In an attempt to make the Soviets worried enough to help Washington negotiate with the North Vietnamese, Nixon secretly instructed the Pentagon in early October 1969 to raise the alert levels of nuclear forces. During the following weeks, as part of what was called the Joint Chiefs of Staff Readiness Test, SAC put its bomber forces on higher alert. The Navy raised the readiness levels of its forces while aircraft carriers and other ships conducted unusual maneuvers to get Moscow’s attention. At the close of the alert, SAC flew sorties of nuclear-armed bombers over northern Alaska on 18-hour stretches. Likely as a sign of Nixon’s concern about Moscow’s support for Hanoi, the U.S. Navy shadowed Soviet merchant ships on their way to Hanoi. It was all low-key; Washington wanted the alert to jar Moscow, not to alarm. Even if they understood Nixon’s underlying purpose, however, the Soviets did not help with Vietnam War diplomacy. In any event, because there was no crisis in its relationship with Washington, Moscow may have seen the U.S. alert actions as pointless or not credible.12

Nixon did not abandon madman threats or alerts. During the September 1970 crisis in Jordan, Nixon expanded the U.S. naval presence in the eastern Mediterranean. During a supposedly off-the-record press briefing, he threatened intervention against Soviet-client Syria, suggesting it was not a bad thing if Moscow thought he was capable of “irrational or unpredictable action.”13 Several years later, Kissinger used Nixon’s tactics during the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. On October 24, 1973, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev informed Washington that Moscow might intervene unilaterally to enforce an agreed cease-fire by sending peacekeepers to help separate Egypt’s beleaguered Third Army from the Israelis. The statement was a bluff, but Kissinger and the U.S. National Security Council (NSC) overreacted by ordering U.S. strategic forces to go on DEFCON 3 as a warning. The Soviets were disconcerted, but did not react. Nixon did not participate in the decision because, reeling from Watergate developments, he was inebriated.14

DEFCON 3 was a higher state of readiness than the usual DEFCON 4, but it was not as threatening as the Cuban missile crisis DEFCON 2. With the Soviets having reached strategic parity with the United States, nuclear threats and confrontations had become too dangerous to consider or endure. This was the last major DEFCON until September 11, 2001. Nevertheless, unexpected incidents, such as false warnings of missile attacks or misunderstandings over military exercises (Able Archer ’83), illuminated the continued perils of the superpower nuclear competition.

The history of nuclear threats and crises demonstrates that U.S. leaders found it easier to try to overawe the Soviets or the Chinese during the 1950s when the retaliatory capability of these adversaries was small or nonexistent. By the 1960s, confrontations were all too dangerous, as Kennedy learned, not least during a September 1963 NSC meeting when he was told how much devastation the Soviets could inflict on the United States.15 Thus, in the context of mutual assured destruction, threats to use nuclear weapons have low credibility because of their suicidal nature. Yet, threat language, including Putin’s recent outbursts, must be assessed carefully. The terrible carnage in Ukraine raises the question as to whether Putin would break international norms by using nuclear weapons. Just as troubling is the prospect that if Putin raised alert levels during this crisis, the attendant dangers of accidents, incidents, or miscalculations could produce the escalation that nobody wants.

ENDNOTES

1. Matthew Jones, After Hiroshima: The United States, Race, and Nuclear Weapons in Asia, 1945–1965 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 68. For U.S. presidents and the nuclear taboo, see Nina Tannenwald, The Nuclear Taboo: The United States and the Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons Since 1945 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

2. Jones, After Hiroshima, pp. 158–159; U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Memorandum of meeting with the president, Washington, D.C., February 17, 1965, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb517-Nixon-Kissinger-and-the-Madman-Strategy-during-Vietnam-War/doc%201A%20DDE%20and%20LBJ%201965.pdf; Benjamin H. Read to Dean Rusk, memorandum, March 4, 1965, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb517-Nixon-Kissinger-and-the-Madman-Strategy-during-Vietnam-War/Doc%201B%20Read%20to%20Dean%20Rusk,%204%20March%201965.pdf.

3. Gordon H. Chang and He Di, “The Absence of War in the U.S.-China Confrontation Over Quemoy and Matsu in 1954–1955: Contingency, Luck, Deterrence?” The American Historical Review, Vol. 98, No. 5 (December 1993): 1500–1524.

4. Center for Naval Analyses, “Suez Crisis, 1956 (U),” CRC 262, April 1974, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515408/doc-5-cna-suez-1956.pdf; U.S. Strategic Air Command (SAC), “Monthly History: 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing,” October-December 1956, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515409/doc-6-1956-55-srw-oct-dec-56.pdf.

5. William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003), pp. 359–360.

6. See George S. Dragnich, “The Lebanon Operation of 1958: A Study of the Crisis Role of the Sixth Fleet (U),” Center for Naval Analysis, September 1970, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515410/doc-7-cna-lebanon-1958.pdf; Headquarters Second Air Force, “Second Air Force Historical Data (Unclassified Title) From 1 July to 31 December 1958,” May 1959, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515411/doc-8-2nd-af-history-1958.pdf; SAC, “Sixteenth Air Force, 1 July-31 December 1958 (Unclassified Title),” n.d., https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515412/doc-9-16th-af-1958.pdf; Jacob Van Staaveren, “Air Operations in the Taiwan Crisis of 1958 (U),” USAF Historical Division Liaison Office, November 1962, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515413/doc-10-taiwan-1958.pdf; M.H. Halperin, “The 1958 Taiwan Straits Crisis: An Analysis (U),” RAND Corp., RM-4803-ISA, January 1966, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20791449/halperin-summary-of-study.pdf. See also Gordon H. Chang, Friends and Enemies: The United States, China, and the Soviet Union, 1948–1972 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990), pp. 86–201.

7. UK Mission to the United Nations, Telegram to UK Foreign Office, No. 1071, September 21, 1958, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/4316143/Document-05-United-Kingdom-Mission-to-the-United.pdf.

8. See U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Unclassified memorandum on uniform readiness conditions, 3M-833-59, January 3, 1961, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515420/doc-17-1961-1-3-sm-833-59-remove-blue-mark-on-p-1.pdf; U.S. Commander in Chief Europe to U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Communication, May 16, 1960, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515421/doc-18-5-16-60-from-cincerur.pdf; U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff to U.S. Commander in Chief Europe, Communication, May 15, 1960, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515422/doc-19-5-16-60-jcs-from-douglas.pdf; U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff to U.S. Commander in Chief Europe, Communication, May 16, 1960, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515423/doc-20-5-16-60-re-press.pdf; U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff to U.S. Army Attache Ottawa, Communication, May 16, 1960, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20515424/doc-21-5-16-60-to-ottawa.pdf.

9. Among the estimable accounts of U.S. President John F. Kennedy’s and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s missile crisis decision-making, see Taubman, Khrushchev, pp. 529–577; Sheldon M. Stern, Averting “the Final Failure”: John F. Kennedy and the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis Meetings (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003). For DEFCON 2, see SAC, “Strategic Air Command Operations in the Cuban Crisis of 1962,” Historical Study, Vol. 1, n.d., https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20591109/08-us-strategic-air-command-history-and-research-division-historical-study-no-90-vol-i-strategic-air-command-operations-during-the-cuban-crisis-of-1962-circa-1963-top-secret-excised-copy.pdf; M.V. Forrestal to MacGeorge Bundy, Memorandum, October 24, 1962, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20589957/09.pdf; Col. L.J. Legere, Memorandum on daily White House staff meeting, October 24, 1962, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20589958/10.pdf.

10. William Burr and Jeffrey P. Kimball, Nixon’s Nuclear Specter: The Secret Alert of 1969, Madman Diplomacy, and the Vietnam War (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2015), pp. 50–65. For “chips into the pot,” see “Kissinger,” n.d., https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nukevault/ebb517-Nixon-Kissinger-and-the-Madman-Strategy-during-Vietnam-War/doc%2022%208-10-72%20Kissinger%20conv%20with%20G.%20Tucker.pdf.

11. Burr and Kimball, Nixon’s Nuclear Specter, ch. 3–7.

12. Ibid., pp. 265–309. See also Thomas Schwartz, Henry Kissinger and American Power (New York:

Hill & Wang, 2020), pp. 83–84.

13. Burr and Kimball, Nixon’s Nuclear Specter, p. 329.

14. Schwartz, Henry Kissinger and American Power, pp. 239–242; Raymond L. Garthoff, Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations From Nixon to Reagan (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1994), pp. 420–428. See also Martin Indyk, Master of the Game: Henry Kissinger and the Art of Middle East Diplomacy (New York: Knopf, 2021), pp. 178–183. For DEFCON 3, see U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Status of Actions Report, Operations Planners Group (OPG),” October 1973, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20589944/22.pdf; SAC, “History of Strategic Air Command FY 1974,” Historical Study, No. 142, January 28, 1974, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20589945/23.pdf; SAC, “Chronology: Middle East Crisis (U),” Historical Study, No. 139, December 12, 1973, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20589946/24.pdf; SAC, “Second Air Force Chronology of Middle East Contingency, 6 October-9 November 1973,” n.d., https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/20589947/25.pdf.

15. Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, “Summary Record of the 517th Meeting of the National Security Council, September 12, 1963,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume VIII, National Security Policy (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1996), doc. 141.

William Burr, a senior analyst with the National Security Archive at George Washington University, directs the Archive's nuclear security documentation project. Jeffrey Kimball is an American historian and emeritus professor at Miami University who has argued that threats to use nuclear weapons have not been effective at advancing the U.S. foreign policy goals. They are coauthors of Nixon's Nuclear Specter.