Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty to Enter Into Force: What's Next?

November 2020

By Alicia Sanders-Zakre

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) will soon enter into force and become binding international law for its states-parties. The milestone will be meaningful for those nations, but it will also affect countries that have yet to ratify or accede to the pact.

Earlier weapons prohibitions have successfully curbed proliferation and advanced norms against weapons of mass destruction. Within one year of the treaty’s entry into force, its states-parties will convene to discuss these issues and the next steps to strengthen the agreement.

Earlier weapons prohibitions have successfully curbed proliferation and advanced norms against weapons of mass destruction. Within one year of the treaty’s entry into force, its states-parties will convene to discuss these issues and the next steps to strengthen the agreement.

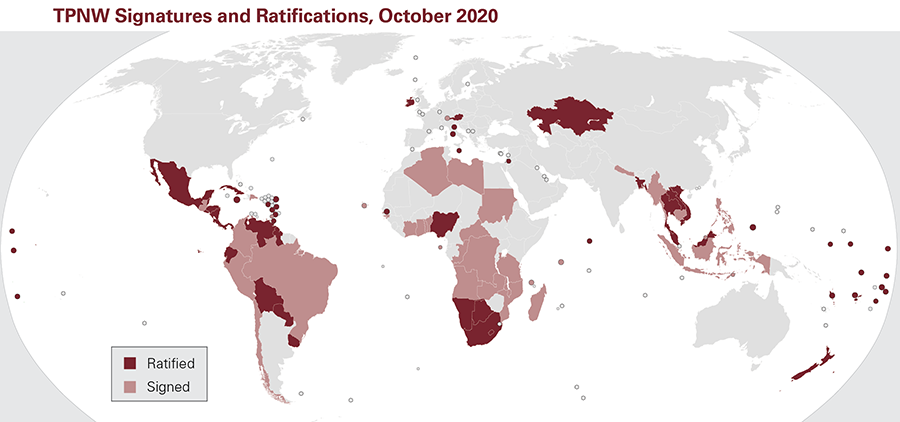

The treaty’s final text was approved by 122 nations at the United Nations in July 2017, but nuclear-armed states boycotted treaty negotiations and have since rejected the treaty as simultaneously irrelevant and dangerous.1 Nevertheless, the majority of the world’s countries have continued to support the TPNW, including by signing and ratifying or acceding.2 States-parties hail from all regions of the world, with many from Africa and Latin America, and the fewest from Europe. According to the treaty, 50 ratifications or accessions must be submitted to the United Nations before the pact can take full legal effect.

Legal Implications for States-Parties

The 50th state, Honduras, ratified the TPNW on October 24, and the treaty will enter into force and take full legal effect for all countries that had ratified or acceded by then on January 22, 2021. For any state that ratifies or accedes to the TPNW after its entry into force, the treaty will take full legal effect 90 days after that state’s ratification or accession.

Before the treaty takes effect, signatories and states-parties are only obligated to refrain from violating the treaty’s object and purpose.3 States-parties must implement positive obligations and adhere to prohibitions, while states that have only signed it are simply required not to violate the object and purpose of the treaty.

Some positive obligations are simple, such as submitting a declaration within 30 days of the treaty’s entry into force about the country’s nuclear-weapon status. Others may take more time, such as adopting additional safeguards agreements with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), implementing national laws, providing assistance to people and places harmed by nuclear weapons use and testing, and urging other states to join the pact.

The treaty requires states-parties to adhere to their current IAEA safeguards agreements and, if they lack one, bring into force a comprehensive safeguards agreement within 18 months of entry into force. Concretely, that means TPNW states-parties that already have an additional protocol to their safeguards agreement are now legally obligated to maintain that protocol. This is an obligation that exceeds the requirements of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), which does not legally require states to adopt or maintain an additional protocol. All states-parties except for Palestine have already brought into force a comprehensive safeguards agreement. Palestine negotiated and signed its agreement in June 2019, but will still need to bring it into force.

States-parties will adopt national measures to implement the treaty’s requirements, both its prohibitions and its positive obligations, and prevent treaty violations on all territory under their jurisdiction or control. Ireland has already adopted such legislation, and the International Committee of the Red Cross provides a model template for other states to do so.4 National measures provide an opportunity for states-parties to spell out how and where they will enforce the treaty. It is up to each state to decide if the law applies to its citizens violating its terms in another country and what penalties will be imposed for violations. Some countries have adopted national implementation measures consistent with their obligations as states-parties to nuclear-weapon-free zones, although these measures only apply within the zone.5

For nations where nuclear test explosions were conducted, the treaty requires them to provide assistance for the people affected by those activities and to take measures to remediate areas under its jurisdiction contaminated by nuclear weapons use and testing.6 Specifically, states must “adequately provide age- and gender-sensitive assistance, without discrimination, including medical care, rehabilitation and psychological support” for affected individuals, “as well as provide for their social and economic inclusion.”7 Several nations with people affected by nuclear weapons use and testing will be states-parties at the time of the treaty’s entry into force, including the Cook Islands, Fiji, and Kazakhstan. Some of these countries already have programs designed to help victims and remediate environments, although programs vary widely.

|

Major Provisions of the TPNW Prohibitions (Article 1) Declarations (Article 2) Safeguards (Article 3) Nuclear-weapon states accession (Article 4) The treaty does not specify which “competent international authority” would be suited to verify irreversible disarmament of a nuclear-armed state that decides to join the treaty, but the treaty allows for an appropriate authority to be designated at a later date. The treaty requires any current or former nuclear-weapon state that seeks to join the prohibition treaty to conclude a safeguards agreement with the IAEA to verify that nuclear materials are not diverted from peaceful to weapons purposes. Positive obligations (Articles 6 and 7) |

The obligation to provide this assistance applies to all states-parties in a position to help.8 The treaty’s Article 7 mandates states-parties’ cooperation to implement the treaty, specifically requiring states-parties in a position to do so to provide “technical, material and financial assistance” to affected states-parties and to victims. States-parties may also support others’ development of national implementation measures or reporting on and destruction of nuclear weapons stockpiles.

Finally, as mandated by Article 12, all states-parties must urge other nations to join. This obligation can be implemented publicly by hosting workshops and calling on all states to join the treaty in statements to relevant diplomatic forums such as the UN General Assembly, IAEA meetings, UN Security Council meetings, and NPT-related sessions.

Article 1 outlines the treaty’s prohibitions: banning states-parties from developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, transferring, possessing, stockpiling, using, or threatening to use nuclear weapons or allowing nuclear weapons to be stationed on their territory. It also prohibits them from assisting, encouraging, or inducing anyone to engage in any of these activities.

As no nuclear-armed states, states hosting nuclear weapons on their territory, or states that rely on the threat to use nuclear weapons in their military doctrines have joined the TPNW at this stage, the most relevant prohibition will likely be the prohibition on assisting, encouraging, or inducing any of these prohibited activities. The treaty still allows states-parties to be in military and political alliances with states not party, including those violating the treaty’s obligations, but there cannot be a significant nuclear dimension to alliance activities. States-parties should discuss how this prohibition on assistance will be understood at meetings of states-parties, basing their interpretations on past precedents in other prohibition treaties. Legal scholars and practitioners have offered potential explanations.9

Political and Normative Implications

The impact of the entry into force of the TPNW on states not party is not as straightforward as the new legal obligations for states-parties. Yet, precedent from the 1999 Mine Ban Treaty and the 2010 Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM) demonstrates that the treaty can also influence their behavior. States-parties and nonstate actors’ actions after the TPNW’s entry into force can shape the norm against nuclear weapons.

Those earlier agreements, together with the TPNW, form a trio of “humanitarian disarmament” treaties, which focus on the consequences of the prohibited weapon and intend to delegitimize the prohibited weapon. Examining the changes in behavior in states not party to those treaties after their entry into force can be informative.

Significantly, the mine ban and cluster munitions ban discouraged production and investment in companies that produce prohibited weapons in states not party. For example, Textron and Orbital ATK, two companies producing cluster munitions in the United States, stopped production after the CCM’s entry into force, even though Washington is not a party to the pact.10 Egypt, also not a party, announced a policy against producing landmines after the Mine Ban Treaty’s entry into force.11 Following the entry into force of the CCM, the U.S.-based mutual fund Eventide Asset Management excluded companies that produce cluster munitions from its investments.12

The Mine Ban Treaty and CCM also affected policies on the weapons’ use and transfer worldwide. Very few states not party have used landmines or cluster munitions since the prohibition treaties entered into force, and states not party have changed their policies on use and transfer. In 2014, for example, the United States announced that it would no longer use landmines outside of the Korean peninsula or assist, encourage, or induce other nations to use, stockpile, produce, or transfer anti-personnel mines outside of Korea. The Trump administration reversed that policy, but more than 100 members of Congress protested the move in a joint letter.13 Since the CCM’s entry into force, the United States has only used cluster munitions once, in an isolated 2009 strike in Yemen; in 2016, it decided to halt transfers of cluster munitions to Saudi Arabia.

States not party may also contribute to implementing the treaty’s positive obligations in addition to adhering to some of the prohibitions. The United States is one of the largest donors to provide support for landmine clearance and victim assistance, despite not being a state-party.14

That companies, financial institutions, and governments have modified their behavior, despite no requirement to do so, illustrates the normative impact of the prohibition treaties. The entry into force of the TPNW has the potential to advance the norm against nuclear weapons.

More than 1,300 elected officials in countries that have not yet joined the TPNW have pledged to work to get their governments on board, and cities and towns around the world have adopted resolutions to demand their governments join the treaty, including capitals in nuclear-armed states, such as Paris and Washington.15 When the treaty enters into force, legislators should urge debates on this new instrument of international law and how their government can comply and participate. Just as cities, universities, and businesses have adopted measures to comply with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, so too can these entities adopt measures to adhere to prohibitions and obligations in the TPNW.

Already, financial institutions have started divesting from nuclear weapons production companies. One of the largest pension funds in the world, the Dutch pension fund ABP, announced in January 2018 that it would divest from nuclear weapons production companies, citing the adoption of the TPNW as a key factor in its decision.16 Given that financial institutions often choose not to invest in companies that produce “controversial weapons,” which are typically weapons prohibited by international law, the entry into force of the TPNW can spur additional divestment.17

The public and private efforts of states-parties to urge other nations, including allies, to join the treaty will help to embed it within political and legal structures, because the treaty is mentioned in statements in international forums in which states not party participate. As public awareness of the treaty grows, so will a general understanding that nuclear weapons are illegal weapons in the eyes of most of the world’s nations. States-parties’ possible creation of infrastructure to implement treaty obligations, including on victim assistance, environmental remediation, verification, and universalization, not only serve to further establish the treaty within international laws and norms, but could also foreseeably involve states not party. Nuclear-armed states could decide to contribute to programs established through the treaty to provide assistance for victims of nuclear weapons use and testing and remediate contaminated environments.

Reviewing Impact and Implementation

Within one year of entry into force, states-parties will convene to discuss and take decisions on the treaty’s implementation at the first meeting of states-parties. Austria has formally offered to host the meeting in Vienna. The first meetings of the mine ban and cluster munition pacts provide some insight into the format and topics likely to come up at the TPNW’s first meeting.

Logistically, states-parties will adopt rules of procedure, which will determine the role for observers at meetings of states-parties, as well as discuss costs for the meetings. The TPNW states that it allows observers to participate in treaty meetings, including states not party and nongovernmental representatives, but the extent of their participation will likely be clarified in the rules of procedure. For example, the rules of procedure adopted at the first meeting of states-parties of the Mine Ban Treaty clarified that observers would not be allowed to participate in decision-making or to make any procedural motion or request. As another example, at the CCM’s first meeting of states-parties, observer states were granted time to update participants on their domestic processes to join the treaty or current status vis-à-vis the treaty, as well as comment on articles in the treaty.18 Other observers, including international organizations and civil society, were invited to deliver statements. Sweden and Switzerland have already indicated that they will observe the TPNW’s meeting of states-parties, and it is likely that many signatory states will also attend.

Structurally, the TPNW’s first meeting of states-parties should follow precedent and leave time for general debate, as well as allow for debate and informal consultations on the treaty’s positive obligations, including victim assistance, environmental remediation, international cooperation and assistance, national implementation, and universalization. States-parties will also have to set the deadline for the elimination of nuclear weapons for nuclear-armed states that join the treaty, as required by Article 4.19

States-parties may start to discuss TPNW provisions on verifying the elimination of nuclear weapons, specifically about designating a “competent international authority,” although given that there are no nuclear-armed states that have joined the treaty, this is not urgent to decide at the first meeting.20 If the treaty enters into force for a nuclear-armed state before states-parties have designated that authority, the UN secretary-general can convene an extraordinary meeting of states-parties to do so. If there is a dispute among states-parties about treaty implementation, they can resolve the dispute themselves, or the meeting of states-parties can contribute to settling the dispute.

Perhaps most importantly, the first meeting of states-parties is a starting point for further action to bring the treaty to life. It will likely conclude with a final report, a declaration committing to the treaty’s urgent implementation, and a plan for follow-up actions to take forward the treaty’s obligations. In Maputo, for example, Mine Ban Treaty states-parties established an intersessional work program, involving regular expert meetings “to advance the achievement of the humanitarian objectives of the convention.” States-parties to the CCM adopted the Vientiane action plan: 66 concrete actions for states-parties to implement treaty provisions, including universalization, victim assistance and environmental remediation, international cooperation and assistance, and national implementation. At the TPNW’s first meeting, states-parties should agree on action steps to advance these obligations, such as establishing working groups, setting specific goals, and, where relevant, setting deadlines to achieve them.21 The detailed Vientiane action plan was first drafted for a preparatory meeting three months prior to the first meeting of states-parties, an option that TPNW states-parties may consider.

Perhaps most importantly, the first meeting of states-parties is a starting point for further action to bring the treaty to life. It will likely conclude with a final report, a declaration committing to the treaty’s urgent implementation, and a plan for follow-up actions to take forward the treaty’s obligations. In Maputo, for example, Mine Ban Treaty states-parties established an intersessional work program, involving regular expert meetings “to advance the achievement of the humanitarian objectives of the convention.” States-parties to the CCM adopted the Vientiane action plan: 66 concrete actions for states-parties to implement treaty provisions, including universalization, victim assistance and environmental remediation, international cooperation and assistance, and national implementation. At the TPNW’s first meeting, states-parties should agree on action steps to advance these obligations, such as establishing working groups, setting specific goals, and, where relevant, setting deadlines to achieve them.21 The detailed Vientiane action plan was first drafted for a preparatory meeting three months prior to the first meeting of states-parties, an option that TPNW states-parties may consider.

Conclusion

The TPNW’s entry into force will trigger the implementation of the treaty’s obligations and prohibitions and can shape the behavior of states not party and advance the norm against nuclear weapons. Some of these changes will happen immediately, but others may take years or decades; no one is under the impression that worldwide nuclear disarmament will happen overnight. Yet as the TPNW continues to take shape, starting with its entry into force and continuing as states-parties meet biennially and once every six years for review conferences, and establishes the infrastructure to implement treaty obligations, the treaty will continue to chip away at the legitimacy of nuclear weapons in the minority of the world’s countries that continue to support them.

After the treaty’s entry into force, the number of states-parties will continue to grow, given the number of states that have signed but not yet ratified and the ongoing processes within many states to complete their ratifications. Even within states that have not signed or started to ratify, public support is behind the ban. Public opinion polls show that large majorities of Australians, Belgians, Finns, French, Germans, Italians, Japanese, Norwegians, and Swedes support their nations joining the treaty. Even 65 percent of Americans, fewer than all those other nations, believe Washington should join.22 Opposition political parties in states not party have pledged to join if their party gains the majority. The TPNW will soon enter into full force, taking its rightful place alongside the treaties that have banned and pushed the elimination of other weapons of mass destruction: the Biological Weapons Convention and the Chemical Weapons Convention. Unlike nuclear weapons, the treaty banning them is here to stay.

ENDNOTES

1. IAEA General Conference, Statement by France on behalf of the P5, September 23, 2020, http://streaming.iaea.org/21487. See NATO Committee on Proliferation, “United States Non-paper: ‘Defense Impacts of Potential United Nations General Assembly Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty,’” AC/333-N(2016)0029 (INV), October 17, 2017.

2. UN General Assembly, A/C.1/74/L.19, October 21, 2019.

3. Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1155 U.N.T.S. 332, May 23, 1969.

4. See Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons Act 2019 (Act. No. 40/2019) (Ir.), http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2019/act/40/enacted/en/pdf; International Committee of the Red Cross, “Model Law for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” March 2019, https://www.icrc.org/en/download/file/93818/190618_en_tpnw_model_law_final_en.pdf.

5. See New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987, http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1987/0086/latest/096be8ed8157721b.pdf.

6. A recent framework on victim assistance and environmental remediation from toxic remnants of war builds on precedents from international disarmament law and international humanitarian law, as well as best practices, to develop principles that will be a useful reference point for Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) states-parties to implement this provision. See Harvard Law School International Human Rights Clinic and Conflict and Environmental Observatory, “Confronting Conflict Pollution: Principles for Assisting Victims of Toxic Remnants of War,” September 2020, http://hrp.law.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Confronting-Conflict-Pollution.pdf.

8. For further explanation on the victim assistance and environmental remediation clauses, see Harvard Law School International Human Rights Clinic, “Victim Assistance and Environmental Remediation in the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons: Myths and Realities,” April 2019, http://hrp.law.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/TPNW_Myths_Realities_April2019.pdf.

9. Stuart Casely-Maslen, “The Nuclear Weapons Prohibition Treaty: Interpreting the Ban on Assisting and Encouraging,” Arms Control Today, October 2018, pp. 11–15.

10. Maaike Beenes and Michel Uiterwaal, “Worldwide Investment in Cluster Munitions: A Shared Responsibility,” PAX, December 2018, https://www.paxforpeace.nl/media/files/pax-worldwide-investment-in-cluster-munitions-2018pdf.pdf.

11. “Egypt: Mine Ban Policy,” Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, October 9, 2018, http://www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2018/egypt/mine-ban-policy.aspx; “United States: Mine Ban Policy,” Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, December 18, 2019, http://www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2019/united-states/mine-ban-policy.aspx.

12. Beenes and Uiterwaal, “Worldwide Investment in Cluster Munitions.”

13. Letter to Defense Secretary Mark Esper, May 6, 2020, https://www.leahy.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/kf%20ac%20Questions%20for%20SecDefense%20Final.pdf.

14. International Campaign to Ban Landmines-Cluster Munition Coalition, “Landmine Monitor 2019,” November 2019, http://www.the-monitor.org/media/3074086/Landmine-Monitor-2019-Report-Final.pdf.

15. International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), “Parliamentarians,” n.d., https://pledge.icanw.org/ (accessed October 17, 2020); ICAN “#ICANSave My City,” n.d., https://cities.icanw.org/ (accessed October 17, 2020).

16. “ABP (The Netherlands),” PAX, July 1, 2020, https://www.dontbankonthebomb.com/abp/.

17. ICAN, “Divestment and Nuclear Weapons,” April 2020, https://www.icanw.org/divestment_and_nuclear_weapons.

18. Convention on Cluster Munitions, “Annotated Provisional Program of Work for the First Meeting of States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions,” CCM/MSP/2010/2/Add.1, November 8, 2010.

19. For an analysis on this decision, see Moritz Kütt and Zia Mian, “Setting the Deadline for Nuclear Weapon Destruction Under the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, Vol. 2, No. 2 (2019): 410–430.

20. For additional analysis about building on the TPNW’s verification measures, including designating a “competent international authority,” see Tamara Patton, Sébastien Philippe, and Zia Mian, “Fit for Purpose: An Evolutionary Strategy for the Implementation and Verification of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, Vol. 2, No. 2 (2019): 387–409; Thomas E. Shea, “On Creating the TPNW Verification System,” Toda Peace Institute Policy Brief, No. 92 (September 2020), https://toda.org/assets/files/resources/policy-briefs/t-pb-92_thomas-shea_tpnw.pdf.

21. For a more detailed overview on addressing victim assistance, environmental remediation, and international cooperation at the first TPNW meeting of states-parties, see Bonnie Docherty, “From Obligation to Action: Advancing Victim Assistance and Environmental Remediation at the First Meeting of States-Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament (forthcoming).

22. Rebecca Davis Gibbons and Stephen Herzog, "75 years after Hiroshima, here are 4 things to know about nuclear disarmament efforts," The Washington Post, August 6, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/08/06/75-years-after-hiroshima-bombing-here-are-4-things-know-about-nuclear-disarmament-efforts/.

Alicia Sanders-Zakre is the policy and research coordinator of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.