"In my home there are few publications that we actually get hard copies of, but [Arms Control Today] is one and it's the only one my husband and I fight over who gets to read it first."

U.S. Aims to Add INF-Range Missiles

October 2020

By Kingston Reif and Shannon Bugos

The United States is moving quickly to develop and deploy missiles formerly banned by the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, according to Trump administration officials, but questions remain about what missiles the military might develop and where they would be based.

“Now that we are out of the INF Treaty, the department is making rapid progress to field ground-launched missiles,” said Deputy Defense Secretary David Norquist on Sept. 10 at the Defense News Conference.

“Now that we are out of the INF Treaty, the department is making rapid progress to field ground-launched missiles,” said Deputy Defense Secretary David Norquist on Sept. 10 at the Defense News Conference.

U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Arms Control Marshall Billingslea in August told Nikkei Asian Review, a Japanese news outlet, that the United States aims to talk with its allies in Asia about where to base such missiles.

The Trump administration wants to “engage in talks with our friends and allies in Asia over the immediate threat that the Chinese nuclear buildup poses, not just to the United States but to them, and the kinds of capabilities that we will need to defend the alliance in the future,” said Billingslea on Aug. 15.

Billingslea specifically highlighted the ground-launched variant of the Tomahawk sea-launched cruise missile that the United States tested shortly after withdrawing from the INF Treaty in August 2019. (See ACT, September 2019.) Washington also tested an intermediate-range ballistic missile in December 2019. (See ACT, January/February 2020.)

The cruise missile is “exactly the kind of defensive capability that countries such as Japan will want and will need for the future,” said Billingslea.

Meanwhile, Defense News reported on Sept. 2 that the U.S. Army is planning to develop a ground-launched missile prototype with a range between 500 and 2,000 kilometers. The Army aims to begin fielding the prototype by 2023.

General Joseph Martin, vice chief of staff of the Army, said on Aug. 21 that the Army is “looking at land-based, land-launched Tomahawk missiles and SM-6s, which are in the Navy’s inventory.”

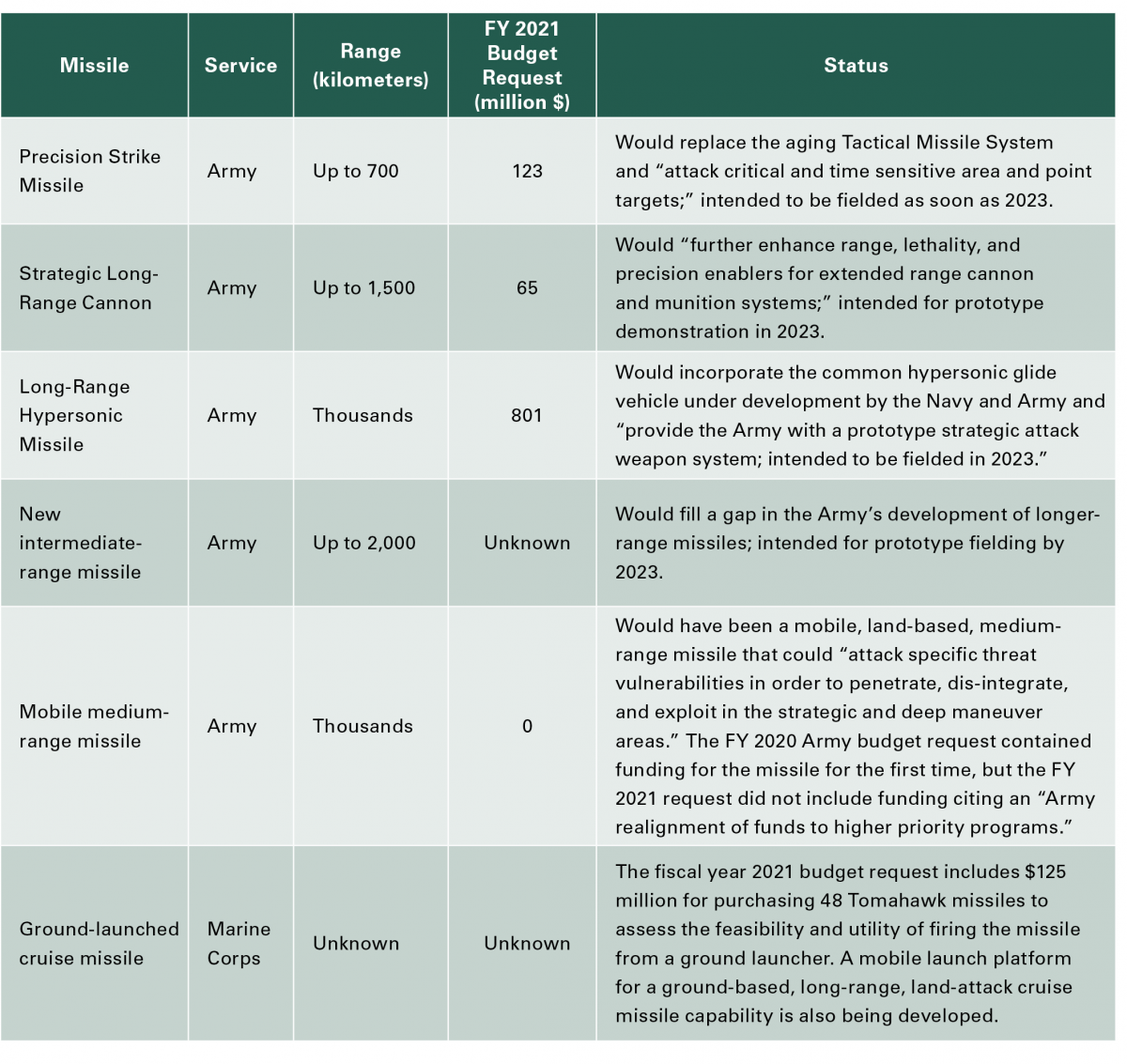

The new missile would join other ground-launched missiles already under development by the Army with a range formally prohibited by the treaty, including the Precision Strike Missile and the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon.

“What we want to do is provide arrows in the quiver… options to our combatant commanders that present multiple dilemmas to our competitors,” Brig. Gen. John Rafferty, the head of the Army’s development of long-range fires, told Breaking Defense, on Sept. 8. “That’s how we deter.”

The Marine Corps fiscal year 2021 budget request released in February included funds to purchase Tomahawk missiles, ostensibly for use as a ground-launched capability. (See ACT, June 2020.)

In October 2019, Taro Kono, Japan’s defense minister, downplayed the idea of Tokyo hosting INF-range missiles from the United States, saying that the two countries “have not been discussing any of it.” (See ACT, December 2019.) Australia and South Korea have also poured cold water on the prospect.

Both China and Russia responded to Billingslea’s remarks, saying they will respond if the United States deploys new ground-launched missiles.

“China firmly opposes U.S. plan to deploy land-based medium-range missiles in the Asia Pacific,” said Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian Aug. 21. “If the U.S. is bent on going down the wrong path, China is compelled to take necessary countermeasures to firmly safeguard its security interests.”

Russian Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said on Aug. 20 that, “Undoubtedly, the deployment of new American missile systems in the region would provoke a dangerous new round of the arms race.” Such a move by Washington “would call for compensatory response measures,” she added.

Meanwhile, Billingslea rejected the idea of a moratorium on deploying missiles that were once banned by the INF Treaty, a proposal made by Russian President Vladimir Putin after the U.S. withdrawal.

“I really wouldn’t spend a lot of time thinking about or worrying about an INF moratorium because, simply put, that’s not going to happen,” said Billingslea during a June 24 press briefing.

NATO officially rejected the proposal in September 2019. France and Italy have acknowledged the moratorium proposal as an opportunity for dialogue.

Signed in 1987, the INF Treaty led to the elimination of 2,692 U.S. and Soviet Union nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers.