“Right after I graduated, I interned with the Arms Control Association. It was terrific.”

Extending New START Is in America's National Security Interest

January/February 2019

By Frank Klotz

On December 4, 2018, the United States officially declared that Russia’s ongoing violation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty constitutes a material breach of the treaty and that the United States will suspend its obligations under the treaty in 60 days unless Russia returns to full and verifiable compliance.1

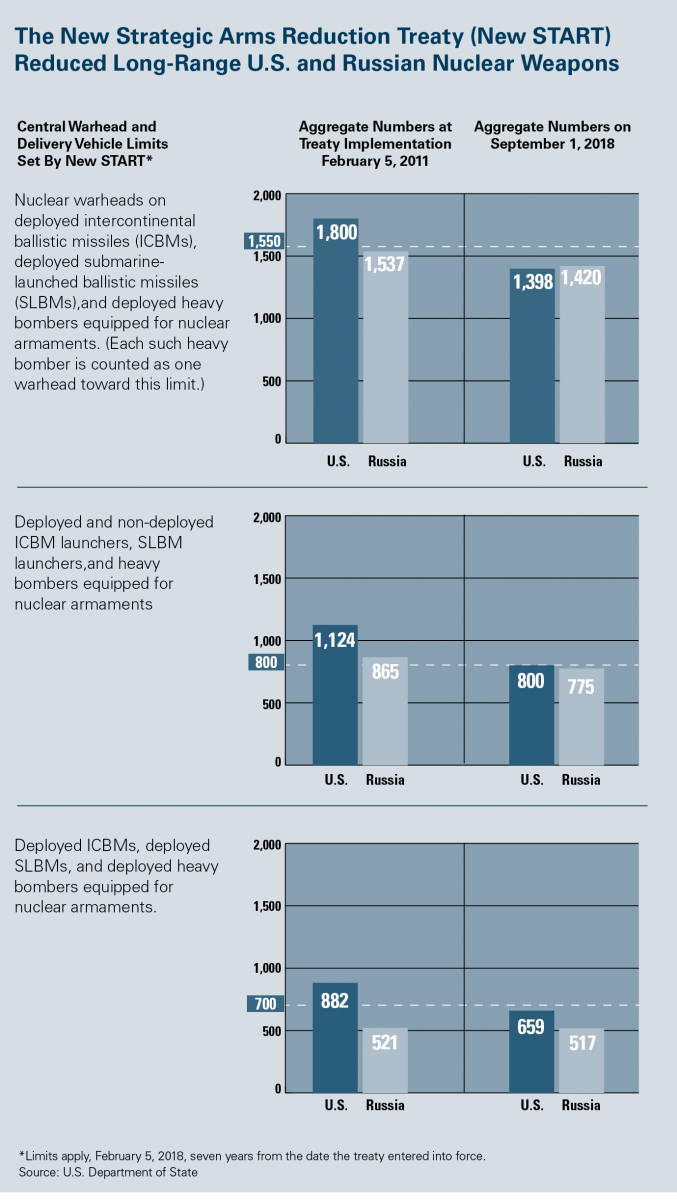

If the United States ultimately follows through on this course of action, as seems likely, only one bilateral agreement would remain that mutually constrains the size of the U.S. and Russian nuclear forces. Moreover, that one agreement, the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), is due to expire in less than three years, that is, 10 years from the date it entered into force.2 The treaty’s terms, however, permit it to be extended for up to one additional five-year period with the approval of the U.S. and Russian presidents, without further review by the legislative bodies of the two countries.

If the United States ultimately follows through on this course of action, as seems likely, only one bilateral agreement would remain that mutually constrains the size of the U.S. and Russian nuclear forces. Moreover, that one agreement, the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), is due to expire in less than three years, that is, 10 years from the date it entered into force.2 The treaty’s terms, however, permit it to be extended for up to one additional five-year period with the approval of the U.S. and Russian presidents, without further review by the legislative bodies of the two countries.

Unlike the case with the INF Treaty, the U.S. Department of State has repeatedly certified that Russia is in compliance with the terms of New START.3 In addition, New START has been and remains in the military and national security interests of the United States. Thus, the most prudent course of action would be to extend New START before it expires in 2021 and thereby gain the time needed to carefully consider the options for a successor agreement or agreements and to negotiate a deal with the Russians.

New START was signed in April 2010 by U.S. President Barack Obama and Russian President Dmitri Medvedev. It entered into force in February 2011, following approval by Russia's Duma and Federation Council and after a particularly rancorous debate in the U.S. Senate. The treaty called for the continued reduction of the nuclear forces of both countries, which had begun in the Reagan era.4 It also put in place a comprehensive verification regime, including provisions for on-site inspections at each other’s nuclear-capable bomber, missile, and submarine bases, as well as routine data exchanges and notifications regarding specific activities associated with their respective strategic offensive arms.5 Both sides met the February 2018 deadline for reducing their existing nuclear forces to the treaty's mandated limits. In addition, as of late 2018, they had each conducted more than 140 on-site inspections and together had exchanged almost 17,000 notifications related to their strategic nuclear forces and facilities.6

Whether the current U.S. administration will opt to extend New START, as permitted by the treaty, is uncertain. Shortly after entering office in January 2017, President Donald Trump reportedly referred to the treaty as a “bad deal” during a phone call with Russian President Vladimir Putin in which the latter raised the possibility of extending the treaty.7 On the other hand, the U.S. president subsequently told reporters in March 2018 that he would like to meet with Putin “to discuss the arms race, which is getting out of control.”8

Indeed, one of the issues that received considerable attention during the run-up to the July 2018 Trump-Putin summit in Helsinki was whether the United States and Russia should agree during the meeting to extend New START.9 That did not happen. Putin did reveal, however, in an interview that he had “reassured President Trump [during the summit] that Russia stands ready to extend this treaty, to prolong it” but that questions regarding U.S. compliance would first have to be decided by “experts.”10

No Firm Position

The U.S. administration apparently does not have a firm position on whether to extend New START before it expires in 2021, nor has it publicly given any indication of when it might have one. In a postsummit follow-up meeting with his Russian counterpart, John Bolton, Trump’s national security adviser, stated in August that the administration was “very, very early in the process of considering” what to do about New START.11 Bolton was a strong critic of the treaty before joining the administration. In congressional testimony in September, senior officials from the departments of State and Defense emphasized that U.S. policy toward extension of New START was still being deliberated within the administration. David Trachtenberg, deputy undersecretary of defense for policy, noted that “any decision on extending the treaty will, and should be, based on a realistic assessment of whether the New START treaty remains in our national security interests in light of overall Russian arms control behavior.”12

So, the key question is whether it is in U.S. national security interests to extend New START before it expires in 2021. Significantly, many members of the one domestic constituency that ought to be the most concerned about the size and posture of the U.S. and Russian nuclear forces—the U.S. military—clearly believe that it is.

At first blush, it may seem counterintuitive that those in charge of the institution with responsibility for designing, developing, and operating nuclear-capable bombers and ballistic missiles would also support an agreement that places constraints on the number of those forces that can be deployed. Yet, ever since the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) started in 1969, U.S. military officers have been actively involved in the negotiations leading to nuclear arms control agreements as members of the U.S. negotiating teams and as participants in the interagency deliberations regarding U.S. goals and objectives. Admittedly, a principal objective of the military with respect to this process has been to ensure the U.S. negotiating teams were well versed in the practical realities of fielding and operating nuclear forces and did not inadvertently offer or accept proposals that would unduly impinge on the military's ability to effectively maintain its bombers and missiles and train their crews.

Arms Control Rationale

Senior U.S. military leaders have also accepted a more conceptually based rationale for supporting the nuclear arms control process. During the 1960s, several U.S. scholars and policymakers had advanced the notion that “armed readiness” and “arms control” can be simultaneously pursued as complementary approaches to protecting national security. Many of the seminal writings associated with this view were studied within military schools during the Cold War. For example, in the 1970s, all U.S. Air Force Academy cadets were required to take a semester-long course on U.S. defense policy that included excerpts from Thomas Schelling's and Morton Halperin's Strategy and Arms Control as assigned reading.13

Regrettably, the treatment of nuclear policy and arms control in professional military education has declined significantly over the past two decades as the focus of attention has shifted to the conduct of military operations in Southwest Asia and countering the threat of terrorism. Nevertheless, a generation of senior military leaders, schooled early in their careers in the classic texts of nuclear deterrence theory, have consistently cited, in their public statements and in their congressional testimony, the benefits that arms control agreements confer.

Foremost among these beliefs is the strongly held view that the transparency and verification measures in the more recent nuclear arms control agreements provide insight into the size, capabilities, and operations of the other side's nuclear forces beyond that provided by more traditional intelligence collection and assessment methods. For example, writing in support of the ratification of New START in 2010, seven former, four-star commanders of U.S. strategic nuclear forces stated that “we will understand Russian strategic forces much better with this treaty than would be the case without it.” They also emphasized that the treaty would contribute to a more stable relationship between the United States and Russia.14

Equally important to senior military leaders has been the role arms control agreements have played in constraining the size and, in certain instances, the capabilities of the other side's nuclear forces. The U.S.-Russian nuclear arms competition during the Cold War was fueled in part by a concern that the other side might achieve a technological breakthrough or build up its forces in such a way as to threaten the survivability of one's own nuclear forces and the ability to retaliate in response to nuclear aggression, thus increasing the incentives for one side or the other to strike or respond quickly, thereby undermining a fundamental prerequisite of stable, mutual deterrence.

Arms control agreements served to ameliorate this concern by capping the overall number of deployed nuclear forces, precluding either side from achieving an overwhelming advantage.15 For the U.S. military, this helped reduce uncertainty and enhance predictability about Russia's capabilities and intentions, allowing it to size and shape U.S. forces with greater confidence in the adequacy of its own investment plans and programs. It also helped free up funding for conventional military capability that might otherwise have been allocated to nuclear forces.

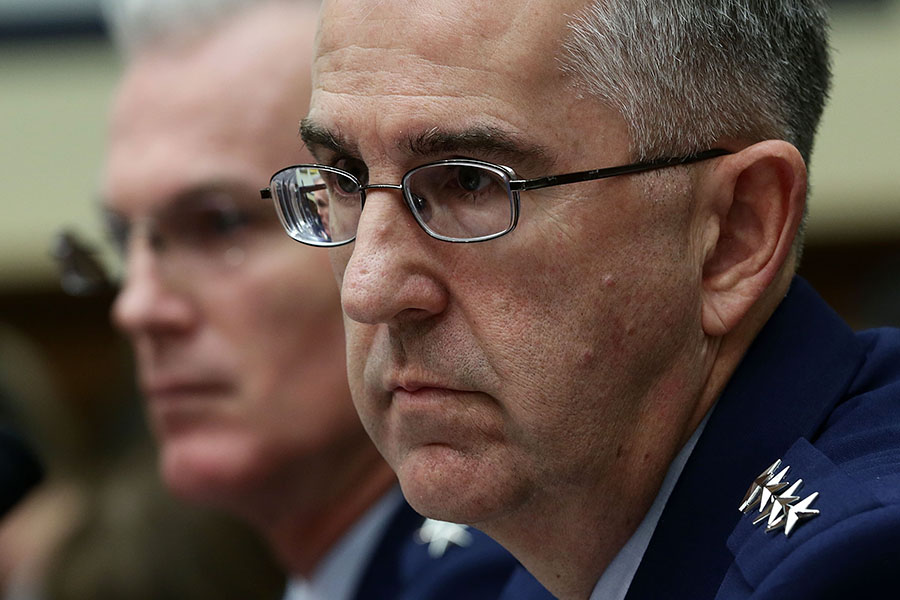

This general view of the benefits of arms control as a complementary strategy to maintaining a survivable, reliable, and effective nuclear deterrence force has carried over to the current considerations of extending New START for an additional five years. In contrast to the noncommittal public statements of civilian national security officials this fall, senior military leaders have been more forthcoming. For example, in a hearing before the House Armed Services Committee in March 2017, General Paul Selva, vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and General John Hyten, commander of U.S. Strategic Command, each expressed strong support for New START, the latter stating that “bilateral, verifiable arms control agreements are essential to our ability to provide an effective deterrent.”16 Lieutenant General Jack Weinstein, Air Force deputy chief of staff for strategic deterrence and nuclear integration, publicly stated that same month that the treaty was of “huge value” to the United States, adding that it has “been good for us.”17 Trump's statements in October 2018 regarding a possible U.S. withdrawal from the INF Treaty has also prompted letters from former national security officials, including retired senior military officers, to salvage the INF Treaty and extend New START.18

In addition to concerns about strategic stability and mutual deterrence, the U.S. military's support for New START reflects very practical considerations about current programs and defense budgets. The Defense Department has embarked on a comprehensive, multiyear effort to modernize its aging fleet of bombers, intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and nuclear submarines. The current “program of record” seeks to replace existing strategic nuclear delivery systems on a roughly one-for-one basis. The new systems would thus fit within the New START limits on deployed and nondeployed systems. Moreover, as long as these limits remain in force, Russian nuclear forces will also be constrained to current and predictable levels. Therefore, the U.S. military can assume with some confidence that its modernization program will be adequate to the task of providing for an effective deterrent for the foreseeable future.

In addition to concerns about strategic stability and mutual deterrence, the U.S. military's support for New START reflects very practical considerations about current programs and defense budgets. The Defense Department has embarked on a comprehensive, multiyear effort to modernize its aging fleet of bombers, intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and nuclear submarines. The current “program of record” seeks to replace existing strategic nuclear delivery systems on a roughly one-for-one basis. The new systems would thus fit within the New START limits on deployed and nondeployed systems. Moreover, as long as these limits remain in force, Russian nuclear forces will also be constrained to current and predictable levels. Therefore, the U.S. military can assume with some confidence that its modernization program will be adequate to the task of providing for an effective deterrent for the foreseeable future.

Additionally, the U.S. nuclear sustainment and modernization program that Trump inherited from his predecessor, even within New START force limits, is estimated by the Congressional Budget Office to cost $1.2 trillion dollars over 30 years (in 2017 dollars and, therefore, higher when accounting for inflation).19 An unconstrained buildup would certainly cost far more. The United States and Russia would not necessarily embark on a significant buildup of their respective strategic offensive forces in the absence of New START or a subsequent agreement, but there would be no treaty obligations preventing them from doing so.

Finally, most senior military leaders acknowledge privately, but for understandable reasons do not state in public, that support for the current nuclear modernization program in Congress over the past decade has depended on a bipartisan consensus based in large part on a “grand bargain” that nuclear modernization and nuclear arms control will be pursued simultaneously. The change of leadership in the U.S. House of Representatives will surely test the resiliency of that consensus in the months ahead. Allowing New START to expire without anything to replace it, coupled with a possible formal withdrawal from the INF Treaty, would most likely place additional stress on that consensus, making it much more difficult to rally support for the current program of record to replace the existing force of aging nuclear delivery systems and revitalize the national laboratories and production facilities of the Department of Energy's semiautonomous National Nuclear Security Administration.20

Viable Alternatives?

Are there any viable alternatives to extending New START that would provide U.S. military planners the same level of certainty about U.S.-Russian strategic nuclear balance and thus the adequacy of current and future U.S. nuclear deterrence capabilities? Although this topic requires considerable thought and discussion, a few general points can be ventured at this stage.

One possible option is to negotiate a new treaty that retains the most salient features of New START, such as limits on deployed forces and robust transparency and verification measures, but addresses matters of particular importance to the United States. The Senate resolution on ratification of New START had expressed concern about the disparity in the number of nonstrategic (theater) nuclear weapons possessed by Russia compared to the number of nonstrategic nuclear weapons deployed by the United States in Europe, and the Obama administration sought to quickly follow New START with negotiations to deal with these systems.21 Those negotiations never took place. More recently, the United States has expressed concern about several new types of nuclear delivery systems that have been developed by Russia and publicly touted by Putin.22 Of course, in any negotiations for a new treaty, the Russians will have their own list of desiderata, including limiting U.S. missile defenses and the deployment of highly precise conventional weapons that could potentially be used to attack Russian nuclear forces and command, control, and communications systems. Even in the unlikely situation that these technically complex and politically fraught issues could be set aside or speedily resolved in the interest of negotiating a successor agreement, the process would still take time, certainly longer than the two years that remain before the treaty expires, if history is any guide.

Another option that has been floated is to replace New START with an agreement like the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty, also known as the Moscow Treaty. Bolton has reportedly described this notion as a “possibility.”23 The treaty was signed by President George W. Bush and Putin in May 2002 after negotiations that lasted only six months. It required both sides to reduce the number of “operationally deployed strategic nuclear weapons” to a level between 1,700 and 2,200. Unlike previous U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control agreements that included many pages of lengthy articles, protocols, and annexes, this treaty was less than two pages long, in large part because it did not include any verification provisions. For Bush administration officials, these were unnecessary because the treaty could rely on the verification regime established in the first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I), which was still in force at the time and would be in place for at least another seven years.24 As it turned out, START I expired in 2009 with no replacement or verification mechanism in place until New START entered into force in 2011 and superseded the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty.

For these and other reasons, this treaty has been criticized as not being “serious arms control.”25 This charge belies a rather narrow view of what constitutes arms control. Despite its brevity, the treaty nevertheless codified in a legally binding manner the desire of both sides to significantly constrain the number of warheads and bombs deployed on ICBMs, on submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and on nuclear-capable bombers. For the United States, this meant reducing the existing force of these weapons by roughly two-thirds. Moreover, because it was framed as a treaty, the agreement was subject to consideration by the U.S. Senate. The resolution of advice and consent to ratification was passed by a unanimous (95-0) vote, thus placing a bipartisan stamp of approval on the process of the further nuclear arms reductions that Bush had signaled he was willing to take unilaterally.26 If that is not serious arms control, it raises the question of what is.

Whether the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty constitutes a model for replacing New START is an entirely different matter. Treaty critics have a point in arguing that it was the product of a unique set of political and economic circumstances in both countries when it was negotiated and that the strategic context and relationship between the two countries are very different today. For example, if New START expires in 2021, there would be no legally binding verification regime in place to give either side the same level of confidence that the other was abiding by the terms of a successor agreement like the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty. Given the emphasis the Congress has traditionally placed on verification and compliance, this would certainly be a political deal breaker.

A third possible option would be to allow New START to expire with U.S. and Russian presidents unilaterally or jointly declaring that their countries will voluntary abide by the existing limits. They could even add that they would continue to follow the major practices of the current verification regime (e.g., data exchanges, notifications, and on-site inspections). The notion of a less formal approach to arms control certainly has a respectable scholarly pedigree. In 1961, Schelling and Halperin wrote that “a more variegated and flexible concept of arms control is necessary—one that recognizes that the degree of formality may range from a formal treaty with detailed specifications, at one end of the scale, through executive agreements, explicit but informal understandings, tacit understandings, to self-restraint that is consciously contingent on each other’s behavior.”27

In fact, all of these elements have been part of the U.S.-Russian strategic relationship at some time and in some form and fashion. During the Cold War, for instance, the two superpowers developed certain norms and modes of behavior regarding military actions that were implicit and, in some cases, explicit in nature, such as avoiding situations in which their military forces might come into direct contact during a crisis or conflict. Whether a nonbinding, informal, or tacit agreement to limit the number of strategic nuclear forces possessed by Russia would provide the level of transparency and predictability that senior U.S. military leaders have come to value is questionable.

Pursuing any of these options or some variant or combination of them will certainly take time. Given the current state of U.S.-Russian relations and the fact the 2020 presidential campaign for all intents and purposes has already begun, it is highly unlikely that two years will be sufficient to accomplish the task. Whatever happens, the existing mutual limits on strategic nuclear forces and the associated transparency and verification measures of New START should not be allowed to expire without replacement. It is manifestly in the best interests of the United States and Russia to agree to extend New START as soon as possible, rather than waiting until the last minute to broker a deal.

Difficult Environment

The difficulties of getting to “yes” on an agreement to extend New START, much less an entirely new nuclear arms control agreement or treaty, should not be underestimated. As noted earlier, the U.S.-Russian relationship is currently burdened by sharp differences in the nuclear realm, such as compliance issues and development of new strategic capabilities. The INF Treaty compliance disputes, in particular, cast a shadow over the prospects. In December, General Joseph Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, pointed this out. “I will obviously not make this decision. I’ll make recommendations,” he said. “But it’s very difficult for me to envision progress in extending (New START)…if the foundation of that is non-compliance with the INF Treaty.”28

To make matters worse, U.S.-Russian discussions on nuclear matters have virtually ground to a halt. They certainly do not exhibit the same intensity, nor do they occur with the same frequency as they did during the Cold War and the first two decades thereafter. Efforts to hold “strategic stability” talks over the past two years have unfortunately faltered due a lack of purpose and seriousness on both sides and as Washington and Moscow take various “retaliatory” measures against one another that render holding talks on any topic politically problematic.

Yet, even at the height of the Cold War and despite profound differences in many other aspects of their relationship, the United States and Russia managed to engage in substantive official and unofficial (Track II) discussions on strategic nuclear matters and, over time, to develop a deeper understanding of each other’s points of view and concerns. Moreover, this ongoing dialogue laid the groundwork necessary to successfully negotiate several different nuclear arms control agreements over a 40-year period. The best way to start the process of addressing the factors that currently cloud the nuclear relationship between the two countries would be to launch a new, more robust series of discussions on nuclear deterrence and arms control involving current and former U.S. and Russian diplomats, senior military officials, and technical experts and to consciously insulate that dialogue from other vagaries in the overall bilateral relationship.

Finally, the current political situation within the United States will present challenges in achieving a broad domestic consensus in support of extending New START. In November, bills in support of doing so and bills designed to constrain the administration's freedom of maneuver on the issue were introduced in the Senate and the House.29 Whether any of the proposed language will ever become law is questionable, especially given the new reality of divided control of the two chambers.

Yet, Congress may well become the focus of debate on extending New START before it expires, especially given the executive branch's current reticence to elaborate its views in public. Proactively engaging members of Congress and their staffs in discussions on how nuclear arms control in general and New START in particular serve U.S. military and national security interests would be time well spent.

ENDNOTES

1. U.S. Department of State, “Press Availability at NATO Headquarters,” December 4, 2018, https://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2018/12/287873.htm. On the same day, the United States’ European allies “strongly supported” the U.S. finding of material breach. NATO, “Statement on the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty Issued by the NATO Foreign Ministers,” December 2018, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_161122.htm.

2. For the text of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), see U.S. Department of State, “New START: Treaty Text,” n.d., https://www.state.gov/t/avc/newstart/c44126.htm (accessed December 16, 2018).

3. U.S. Department of State, “Annual Report on Implementation of the New START Treaty,” January 2018, p. 4, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/280780.pdf.

4. The treaty limits each side to an aggregate total of 700 deployed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments; 1,550 nuclear warheads on deployed ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments (each such heavy bomber is counted as one warhead toward this limit); and 800 deployed and nondeployed ICBM launchers, SLBM launchers, and heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments.

5. U.S. Department of State, “New START,” n.d., https://www.state.gov/t/avc/newstart/ (accessed December 16, 2018).

6. U.S. Department of State, “New START Treaty Inspection Activities,” n.d., https://www.state.gov/t/avc/newstart/c52405.htm (accessed December 16, 2018). The United States actually carried out more reductions than Russia. The number of systems removed can be derived by comparing the aggregate numbers held by both sides in February 2011 to those held in February 2018. Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance (AVC), U.S. Department of State, “New START Treaty Aggregate Numbers of Strategic Offensive Arms," June 1, 2011, https://2009-2017.state.gov/t/avc/rls/164722.htm; AVC, “New START Treaty Aggregate Numbers of Strategic Offensive Arms," Feburary 22, 2018, https://www.state.gov/t/avc/newstart/278775.htm.

7. Jonathan Landay and David Rohde, “Exclusive: In Call With Putin, Trump Denounced Obama-Era Nuclear Arms Treaty - Sources,” Reuters, February 9, 2017.

8. Jenna Johnson and Anton Troianovski, “Trump Congratulates Putin on His Reelection, Discusses U.S. Russian 'Arms Race,’” The Washington Post, March 20, 2018.

9. For example, see Alexandra Bell and Kingston Reif, “A Real Triumph for Trump: Extend New START,” Breaking Defense, July 14, 2018.

10. “Chris Wallace Interviews Russian President Putin,” Fox News, July 16, 2018.

11. Karen DeYoung, “Bolton and His Russian Counterpart Discuss Arms Control, Syria and Iran,” The Washington Post, August 23, 2018.

12. Kingston Reif, “Republican Senators Back New START,” Arms Control Today, October 2018.

13. Mark E. Smith III and Claude J. Johns Jr., eds., American Defense Policy, 2nd ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1968), pp. 116-128. Smith and Johns were members of the Department of Political Science faculty at the U.S. Air Force Academy.

14. General Larry Welch et al., Letter to Senator Carl Levin et al., July 14, 2010, https://s3.amazonaws.com/ucs-documents/nuclear-weapons/New-START-Letter-2010.pdf.

15. Thomas C. Schelling and Morton H. Halperin, Strategy and Arms Control (New York: Twentieth Century Fund, 1961), pp. 9–14.

16. Military Assessment of Nuclear Deterrence Requirements: Hearing Before the Committee on Armed Services, 115th Cong. 29 (2017). See Stephen Young, “New START Is a Winner,” Union of Concerned Scientists, March 16, 2017, https://allthingsnuclear.org/syoung/new-start-is-a-winner.

17. Aaron Mehta, “Air Force Nuclear Officer: New START Treaty Is ‘Good for Us,’” Defense News, March 2, 2017.

18. Rick Gladstone, “In Bipartisan Pleas, Experts Urge Trump to Save Nuclear Treaty With Russia,” The New York Times, November 8, 2018.

19. U.S. Congressional Budget Office, “Approaches for Managing the Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2017 to 2046,” October 2017, pp. 1–2, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/53211-nuclearforces.pdf.

20. For information on the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) modernization plans and programs, see NNSA, U.S. Department of Energy, “Fiscal Year 2019 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan—Biennial Plan Summary: Report to Congress,” October 2018, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2018/10/f57/FY2019%20SSMP.pdf.

21. “Treaty With Russia on Measures for Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms,” Congress.gov, n.d., https://www.congress.gov/treaty-document/111th-congress/5/resolution-text (accessed December 16, 2018).

22. Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Nuclear Posture Review,” February 2018, p. 8, https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF. See Anton Troianovski, “Putin Claims Russia Is Developing Nuclear Arms Capable of Avoiding Missile Defenses,” The Washington Post, March 1, 2018.

23. DeYoung, "Bolton and His Russian Counterpart Discuss Arms Control, Syria and Iran." As undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, John Bolton was a key figure in the negotiations that led to the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty.

24. For the text of the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty and related documents, see U.S. Department of State, “Treaty Between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Strategic Offensive Reductions (The Moscow Treaty),” May 24, 2002, https://www.state.gov/t/avc/trty/127129.htm. The author was one of these nuclear policy and arms control officials in the Bush administration.

25. For example, Steven Pifer, “John Bolton Keeps Citing This 2002 Pact as an Arms-Control Model. It’s Really Not,” Defense One, November 4, 2018.

26. For example, see Office of the Press Secretary, The White House, “Remarks by the President to Students and Faculty at National Defense University,” May 1, 2001, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/05/20010501-10.html.

27. Thomas C. Schelling and Morton H. Halperin, Strategy and Arms Control (New York: The Twentieth Century Fund, 1961), p. 77.

28. Jonathan Landay and Arshad Mohammed, “Russia Must Scrap or Alter Missiles U.S. Says Violate Arms Treaty,” Reuters, December 6, 2018.

29. For example, Office of Congresswoman Liz Cheney, “Congresswoman Liz Cheney and Senator Cotton Introduce the Stopping Russian Nuclear Aggression Act,” November 28, 2018, https://cheney.house.gov/2018/11/28/stopping-russian-nuclear-aggression-act/; Office of Senator Elizabeth Warren, “Warren, Merkley, Gillibrand, Markey Introduce Bill to Prevent Nuclear Arms Race,” November 29, 2018, https://www.warren.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/warren-merkley-gillibrand-markey-introduce-bill-to-prevent-nuclear-arms-race.

Retired U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General Frank Klotz was undersecretary of energy for nuclear security and administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration from 2014 to 2018 and commander of Air Force Global Strike Command from 2009 to 2011.