“For 50 years, the Arms Control Association has educated citizens around the world to help create broad support for U.S.-led arms control and nonproliferation achievements.”

REMARKS: Banning ‘Killer Robots’: The Legal Obligations of the Martens Clause

October 2018

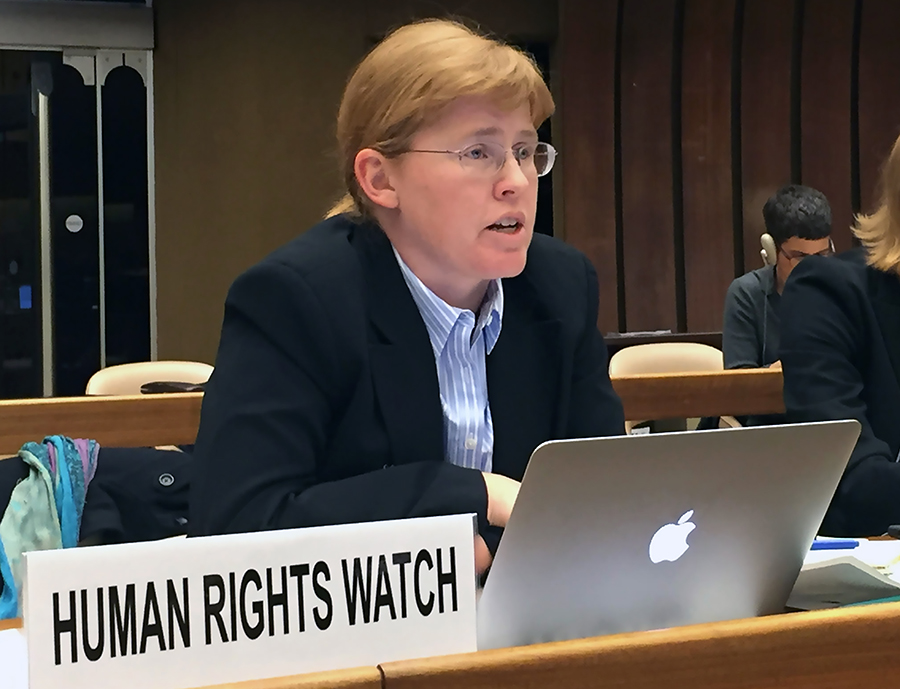

By Bonnie Docherty

For five years, states have highlighted the host of problems with lethal autonomous weapons systems, including legal, moral, accountability, technical, and security concerns. It is time to move on and take action.

Human Rights Watch supports the proposal for a mandate to begin negotiations in 2019 on a legally binding instrument to require meaningful human control over the critical functions of lethal autonomous weapons systems. Such a requirement is effectively the same as a prohibition on weapons that lack such control.

Human Rights Watch supports the proposal for a mandate to begin negotiations in 2019 on a legally binding instrument to require meaningful human control over the critical functions of lethal autonomous weapons systems. Such a requirement is effectively the same as a prohibition on weapons that lack such control.

We were pleased to hear so many states—the vast majority of states—express support for a legally binding instrument prohibiting these systems. We hope that high contracting parties set aside significant time in 2019 to fulfill that mandate—at least four weeks, so that the negotiations could be concluded within one year.

Several states have said the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) discussions should focus on the compliance of lethal autonomous weapons systems with international law and particularly international humanitarian law. We agree that compliance with rules of proportionality and distinction is critical, and we question whether this technology could comply.

But another provision of international humanitarian law must also be considered. The Martens clause, which appears in the Geneva Conventions, Additional Protocol I and the preamble of the CCW, creates a legal obligation for states to consider moral implications when assessing new technology. The clause applies when there is no specific existing law on a topic, which is the case with lethal autonomous weapons systems, also called fully autonomous weapons.

The Martens clause requires in particular that emerging technology comply with the principles of humanity and dictates of public conscience. Fully autonomous weapons would fail this test on both counts. The principles of humanity require humane treatment of others and respect for human life and dignity. Weapons that lack meaningful human control over the critical functions would be unable to comply with these principles.

Fully autonomous weapons would lack compassion, which motivates humans to minimize suffering and killing. They also would lack the legal and ethical judgment necessary to determine the best means for protecting civilians on a case-by-case basis in complex and unpredictable combat environments. As inanimate machines, fully autonomous weapons could not appreciate the value of human life and the significance of its loss. They would base life-and-death determinations on algorithms, objectifying their human targets, whether civilians or combatants. They would thus fail to respect human dignity.

The development of weapons without meaningful human control would run counter to the dictates of public conscience. Many states have called for a prohibition on the weapons. Virtually all states speaking at the CCW meeting have stressed the need to maintain human control over the use of force. Collectively, these statements provide evidence that the public conscience favors human control and objects to fully autonomous weapons.

Experts and the general public have reached similar conclusions. Thousands of artificial intelligence and robotics researchers, along with companies and industry representatives, have called for a ban on fully autonomous weapons. Traditional voices of conscience—faith leaders and Nobel Peace Prize laureates—have echoed those calls, expressing moral outrage at the prospect of losing human control over the use of force. Civil society and the International Committee of the Red Cross have emphasized that law and ethics require human control over the critical functions of a weapon.

In conclusion, the rules of law and morality demand the negotiation of a new legally binding instrument on fully autonomous weapons. An assessment under the Martens clause of the technology shows there is a gap in international law that needs to be filled. Concerns related to the principles of humanity and dictates of public conscience show that the new instrument should ensure that meaningful human control over the use of force is maintained and the development, production, and use of fully autonomous weapons are prohibited.

Bonnie Docherty is a senior researcher in the arms division of Human Rights Watch and a lecturer on law at Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic. This is adapted from her remarks August 29 to the Convention on Conventional Weapons Group of Governmental Experts on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems.