A Question of Dollars and Sense: Assessing the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review

March 2018

By Madelyn Creedon

The Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) is consistent in many respects with long-standing nuclear policies. Yet, certain elements are deeply troubling.

In terms of consistency, it reiterates that the primary mission of U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack; rejects a declaratory no-first-use policy; retains the long-standing policy of ambiguity as to what constitutes U.S. vital interests, although with less ambiguity; seeks to assure allies; and reinforces the U.S commitment to the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). These are pillars of U.S. deterrence policy.

The choices that are troubling include the intention to seek a new low-yield nuclear capability, the rejection of future arms control agreements, and the plan to increase U.S. nuclear weapons production capability. These matters, in particular, deserve close scrutiny by Congress and public debate.

The choices that are troubling include the intention to seek a new low-yield nuclear capability, the rejection of future arms control agreements, and the plan to increase U.S. nuclear weapons production capability. These matters, in particular, deserve close scrutiny by Congress and public debate.

Certainly, the international security environment has been evolving since the Cold War ended and since the previous NPR during the Obama administration. Change was the backdrop for the 2010 NPR and remains the backdrop for the 2018 review, which highlights major nuclear modernization programs by Russia and China, rapid nuclear weapons advances by North Korea, and growing cyberthreats by state and nonstate actors.1

The report on the 2010 NPR concluded that “the threat of global nuclear war has become remote, but the risk of nuclear attack has increased.” This conclusion remains valid. The underlying assumption in the 2018 NPR, however, is that the risk of nuclear attack, although not quantified, has increased, that it is the greatest risk facing the United States, and that the country’s deterrent is not sufficiently robust to counter or deter the increased risk. Alternatively, even if the risk has not increased, the latest NPR report seemingly calls into question whether the U.S. deterrent is sufficiently robust to deter the same level of risk.

Thus, the new report concludes that U.S. nuclear forces must be “supplemented” now. To that end, it calls for the nuclear complex to be positioned to develop new nuclear weapons, possibly resume explosive nuclear testing, increase the size and makeup of the nuclear stockpile, and increase the diversity of the delivery systems. The report argues that without expanding the capabilities of the nuclear enterprise, particularly the ability of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to move beyond its current focus on life-extension programs for warheads, this and future administrations will not be able to tailor deterrence to the changing nature of potential adversaries.

In contrast, the prior NPR report determined that the greatest risks were presented by terrorists with weapons of mass destruction, particularly nuclear or radiological capabilities, and the proliferation of nuclear weapons capabilities to states such as North Korea. Based on this conclusion, significant emphasis was placed on addressing these proliferation and terrorism threats, including securing, consolidating, and eliminating highly enriched uranium (HEU) and plutonium that could be used by terrorists in an improvised nuclear device. Although there is no indication that these threats have diminished, they are not given priority in the 2018 NPR report. One can only hope that the language urging funding trade-offs among programs does not include the programs that prevent proliferation and ensure the security of weapons-usable materials.

The 2010 NPR report by no means ignored “the more familiar challenge of ensuring strategic stability with existing nuclear powers—most notably Russia and China.” Although it identified five pillars to address threats across the spectrum, it certainly did not diminish the importance of deterrence, clearly stating that the United States would maintain safe, secure, reliable, and effective nuclear forces. It recognized that nuclear forces continue “to play an essential role in deterring potential adversaries and reassuring allies and partners around the world as long as nuclear weapons exist.”

Realistically, however, the 2010 review also recognized that nuclear deterrence alone was not the answer but rather that a wide spectrum of highly capable U.S. conventional capabilities, including missile defense, in conjunction with nuclear forces would provide the best deterrent for the United States and its allies and partners.

In a bold step, the 2010 NPR report tried to identify and set the conditions for meaningful compliance with the disarmament provision in NPT Article VI, while clearly recognizing that the conditions were not currently suited to achieve those goals and might not be for many years. Since 2010, unfortunately, the global security conditions have become even less conducive to achieving a world without nuclear weapons. The 2010 report, while aspiring to these goals, reflected a growing concern that the world was approaching a nuclear tipping point where more states and more weapons would be the norm.

In a bold step, the 2010 NPR report tried to identify and set the conditions for meaningful compliance with the disarmament provision in NPT Article VI, while clearly recognizing that the conditions were not currently suited to achieve those goals and might not be for many years. Since 2010, unfortunately, the global security conditions have become even less conducive to achieving a world without nuclear weapons. The 2010 report, while aspiring to these goals, reflected a growing concern that the world was approaching a nuclear tipping point where more states and more weapons would be the norm.

Although the nuclear deal with Iran has removed that country’s nuclear weapons capability for the time being, North Korea’s nuclear weapons capability has qualitatively and quantitatively improved, China and Russia have embarked on nuclear weapons modernization programs, and the nuclear arsenals of India and Pakistan have grown.

Russia, China, and even North Korea are expanding their conventional and nuclear programs to match or offset the U.S. conventional force advantage. The United States has been very public about Russian deployment of a new nuclear-capable missile system in violation of the landmark 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.2 China has continued its assertiveness in the Asia-Pacific region, growing and diversifying its conventional capabilities and modernizing its nuclear forces. While remaining small in number, their nuclear forces are becoming increasingly more capable and survivable.

These disturbing trends are unlikely to change in the near term.

Philosophies articulated in the 2010 NPR report, including the need for a strong and credible deterrent, continue in the new report. The prior report reaffirmed long-standing U.S. policy that “[t]he United States will continue to ensure that in the calculations of any potential opponent, the perceived gains of attacking the United States or its allies and partners would be far outweighed by the unacceptable costs of response” and that “any attack on the United States or our allies and partners, will be defeated, and any use of nuclear weapons will be met with a response that would be effective and overwhelming.” Similarly, the 2018 NPR report concluded that “the highest nuclear policy and strategy priority is to deter potential adversaries from nuclear attack of any scale.”

Different in Tone and Tenor

Notwithstanding such similarities, the new NPR report is remarkably different in tone and tenor from its predecessor, placing the bulk of the emphasis on the nuclear forces and much less emphasis on nuclear terrorism and nonproliferation. This NPR is consistent with the National Security Strategy’s shift to a new era of great power rivalries.3

Although focused and driven primarily by Russian behavior, China’s growing conventional capabilities, including space and cyber capabilities, also shape the decisions in the 2018 report. In addition to the near-term decision to “supplement” the nuclear forces with a low-yield variant of the W76-1 warhead for ballistic missile submarines, the new report lays out a long-term plan to prepare the United States to develop, test, and deploy new nuclear weapons and to increase the size of the nuclear stockpile. In short, prepare for a new arms race.

Although focused and driven primarily by Russian behavior, China’s growing conventional capabilities, including space and cyber capabilities, also shape the decisions in the 2018 report. In addition to the near-term decision to “supplement” the nuclear forces with a low-yield variant of the W76-1 warhead for ballistic missile submarines, the new report lays out a long-term plan to prepare the United States to develop, test, and deploy new nuclear weapons and to increase the size of the nuclear stockpile. In short, prepare for a new arms race.

This new version of a hedging strategy—being able to address geopolitical and technical uncertainty, a key tenant of the 2010 and previous reports—includes a decision to retain more weapons longer and make new weapons faster.

The United States can hedge in two complementary ways. One is by having a robust nuclear weapon production infrastructure that has the design, engineering, and manufacturing capabilities needed to quickly produce new or additional weapons needed to address changes in the threat environment. Another approach is to retain a significant non-deployed inventory of weapons that can be added to current delivery vehicles to address geopolitical threat or technical failure.

One disturbing aspect of the new approach is the apparent decision to keep the last megaton weapon in the U.S. arsenal, the B83. How long this warhead will be retained is unclear, but one section of the NPR report indicates that it will be retained until replaced.

On the other hand, the report continues previous decisions to maintain the nuclear triad and replace the delivery systems: a new Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine, a new intercontinental ballistic missile, a new long-range bomber, and a new air-launched cruise missile. A new addition to the ongoing programs is a sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM). Whether the SLCM goes forward is highly dependent on Russia and whether it continues to violate the INF Treaty or returns to compliance.

The new low-yield warhead, although designed to counter Russia’s growing arsenal of novel nonstrategic systems, may prove to be counterproductive. To deploy the new low-yield warhead, the United States, unlike Russia, will sacrifice some of its strategic warheads because nonstrategic nuclear warheads are not counted under the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). Russia has taken advantage of this fact by substantially increasing its arsenal of nonstrategic weapons, while complying with the limitations on strategic systems. Because the Trident II D5 ballistic missile on U.S. ballistic missile submarines and any warheads on it are counted under New START, the low-yield warhead will be subject to the treaty limits, just like the higher-yield W76-1. In other words, it is a one-for-one trade-off. How many low-yield weapons will be produced is unknown, but having fewer high-yield warheads, such as the W76-1, seems to advantage Russia.

A concept of operations has yet to be explained for the new low-yield weapon. The sea leg of the nuclear triad is the most survivable leg in large part due to the ability of Ohio-class submarines to be invisible in the open ocean. Launching a high-value D5 missile from a ballistic missile submarine will most likely give away its location. China and Russia are expanding their ability to detect a missile launch and will be able to locate a U.S. submarine if it launches a D5 missile. Is having a low-yield warhead worth the risk of exposing the location of a ballistic missile submarine at sea?

Moreover, if the reason to have a low-yield warhead is to respond to Russian first use of a low-yield weapon, rather than sticking to the promise of the 2010 NPR report to use overwhelming force in response to nuclear use, responding with a low-yield warhead also seems to advantage Russia and weaken deterrence. Signaling that a low-yield weapon would be used to respond to low-yield weapon use might persuade Russia to lower the nuclear threshold, thus risking nuclear war-fighting. President Ronald Reagan cautioned against this in 1984 when he said, “A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought. The only value in our two nations possessing nuclear weapons is to make sure they will never be used.”

Budget Challenges

Whether there is the political and budgetary will to implement the 2018 NPR report remains to be seen.

The biggest challenge laid out in the 2018 report is the new assignment for the NNSA. The NNSA is well into the process of fixing its aging infrastructure, but has a long way to go. It cannot fund these very expensive, one-of-a-kind nuclear facilities within its existing budget plan. A new state-of-the-art HEU storage facility is complete, and the design of the new uranium processing facility is well along. The NNSA is deciding where to build a new plutonium facility, but needs new funding, and the 1976-era PF-4 plutonium facility at the Los Alamos National Laboratory must be replaced at some point. Continuing resolutions in Congress and changing requirements add to the cost and delay schedules.

The NNSA does not have out-year funding to implement the next generation of stockpile stewardship, build new experimental facilities, conduct and diagnose more subcritical experiments at the Nevada National Security Site, expand computational capabilities necessary to maintain the current stockpile, identify and resolve future problems, conduct life extension programs, and support the fight against nuclear terrorism and proliferation.

The NNSA does not have out-year funding to implement the next generation of stockpile stewardship, build new experimental facilities, conduct and diagnose more subcritical experiments at the Nevada National Security Site, expand computational capabilities necessary to maintain the current stockpile, identify and resolve future problems, conduct life extension programs, and support the fight against nuclear terrorism and proliferation.

New capabilities such as the stockpile responsiveness program and other new efforts to challenge the design and manufacturing skills of the nuclear complex will also need new funding. As the 2018 NPR report points out, although there is a new tritium-extraction facility at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina, the NNSA needs a new tritium loading facility. Lithium facilities must be constructed or a commercial source identified. In the long term, enrichment capabilities must be built to provide suitable low-enriched uranium fuel to produce tritium. If indeed the 2018 NPR is setting the NNSA on a course to build more weapons and new weapons, the NNSA budget must increase significantly.

Not mentioned at all in the NPR report is the cost, which could run into the low billions, to safely tear down the old buildings, such as building 9212 at the Y-12 National Security Complex at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, as the new buildings become operational. Transporting nuclear weapons, materials, and parts is also a mission not mentioned. Because funding for the new secure trailers for the Secure Transportation Asset program4 has been delayed, the new trailers will not be available until 2024, and the program is understaffed.

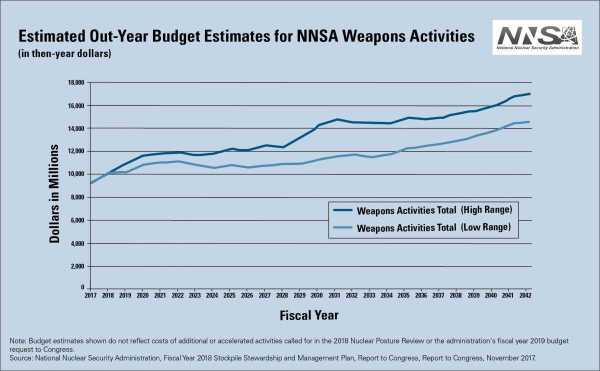

The fiscal year 2019 budget that President Donald Trump sent to Congress in February calls for $11 billion for NNSA weapons activities. That would be an increase of about $800 million, or 8 percent, from the fiscal year 2018 request and $1.8 billion more, a 20 percent jump, from the enacted funding for fiscal year 2017. It is not clear how much of those budget requests will be enacted by Congress, nor is it clear necessary increases will be sustained under future administrations.

Historically, neither Congress, the Department of Defense, nor the Office of Management and Budget have shown an inclination to fully fund the NNSA program of record, let alone the new initiatives such as those outlined in the 2018 NPR report. Even though the NNSA budget has increased by 60 percent since 2010, the efforts to address the decades of inattention to the infrastructure have not been fully funded. Similarly, stockpile surveillance work and the extremely successful Stockpile Stewardship Program have been cut back to support the ongoing warhead life extension programs.

The NNSA’s challenge is further complicated by an inability, imposed by Congress, to hire the skilled federal workforce needed to design and oversee implementation of the existing programs. Even though the NNSA’s work has grown significantly over the past five years, Congress continues to impose an arbitrary cap on federal staff at 1,690 employees.

The labs, plants, and the NNSA will need to recruit and train new staff and retain new and existing staff to carry out the life extension programs, maintain a robust Stockpile Stewardship Program, and take on the many new initiatives. Staffing efforts, including for the Secure Transportation Asset program, is further hindered by the year-long security clearance process, and the backlog is growing.

Although the 2018 NPR report puts considerable emphasis on the relatively low cost of nuclear deterrence in the overall defense budget, the NNSA’s entire budget already supports the spectrum of deterrence. There are no trade-offs and no untapped sources of funding.

A significant omission in the NPR report is how the NNSA will get the new funding. History has taught us that having the Defense Department move its money to the NNSA is not the answer. That approach, although well meaning, led to dissent and discord in the Defense Department-NNSA relationship. Only an increase in the overall defense budget, which includes the Defense Department and NNSA, can support the full range of efforts. Even the new low-yield weapon will be expensive, despite assertions in the NPR report that it will be easy, fast, and cheap.

The Defense Department must not neglect its efforts to maintain its nuclear enterprise and the existing delivery systems until the new platforms are fielded. This effort, started under Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, is essential to the long-term well-being of the nuclear enterprise. The well-documented loss of focus on all things nuclear starting with Operation Desert Storm forced the military services to devote resources, attention, and a renewed commitment to sustain the nuclear deterrent and the men and women who support it.

The NPR report includes language supporting this ongoing effort, which has already shown results. “The Service reforms we have accordingly implemented were long overdue, and the Department of Defense remains fully committed to properly supporting the Service members who protect the United States against nuclear threats.”

The 2018 NPR report also expresses strong support for upgrading the nuclear command, control, communications, and early-warning system known as NC3.5 Here again, efforts to revitalize the system have been underway for years, such as new secured protected communications and early-warning satellites, but funding is always a challenge, particularly for the related terminals and ground systems.

Role for Arms Control

Finally, the NPR report argues that “arms control can contribute to U.S., allied, and partner security by helping to manage strategic competition among states. By codifying mutually agreed-upon nuclear postures in a verifiable and enforceable manner, arms control can help establish a useful degree of cooperation and confidence among states. It can foster transparency, understanding, and predictability in adversary relations, thereby reducing the risk of misunderstanding and miscalculation.”

New START meets these criteria. Extending New START, whose central limits were achieved on February 5 by Russia and the United States, would further support these goals. Russia has not shown any interest in a new treaty, but it did leave open the door for discussion to extend New START by five years, an option provided in the treaty. Discussions beginning this summer or fall to extend New START would go a long way toward demonstrating that arms control remains important.

Does the Trump administration NPR put an end to the decades-long reduction of the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. national security and military strategy? Does it position the United States for a new nuclear arms race and a return to nuclear weapons testing after a 26-year moratorium? Is there the political and budgetary will to implement this new, more aggressive nuclear force posture and policy and its supporting infrastructure? Does the NPR report present an appropriate approach given an increasingly uncertain and competitive world? These questions need to be addressed as the administration’s newly released fiscal year 2019 budget request is considered by Congress.

ENDNOTES

1 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Nuclear Posture Review,” February 2018, https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF; U.S. Department of Defense, “Nuclear Posture Review Report,” April 2010, https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/defenseReviews/NPR/2010_Nuclear_Posture_Review_Report.pdf.

2 Michael R. Gordon, “Russia Has Deployed Missile Barred by Treaty, U.S. General Tells Congress,” The New York Times, March 8, 2017.

3 “National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” December 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

4 Office of Secure Transportation, National Nuclear Security Administration, “Ten-Year Site Plan FY2012 Through FY2021,” April 2011, https://nnsa.energy.gov/sites/default/files/nnsa/inlinefiles/OST%20TYSP%202012-2021%20053111%20cjs.pdf.

5 U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications: Update on Air Force Oversight Effort and Selected Acquisition Programs,” GAO-17-641R, August 15, 2017.

Madelyn Creedon was the Department of Energy’s principal deputy administrator for the National Nuclear Security Administration from 2014 to 2017 and was assistant secretary of defense for global strategic affairs from 2011 to 2014.