“We continue to count on the valuable contributions of the Arms Control Association.”

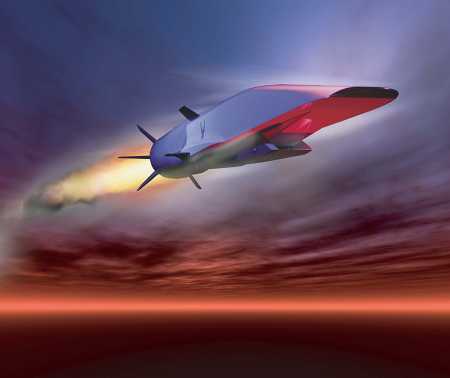

Hypersonic Advances Spark Concern

January/February 2018

By Kingston Reif

The Defense Department in the fall conducted its latest test of a hypersonic missile, a new type of high-speed weapon that potentially holds great military promise but also great peril as the United States and other nations seeking to exploit the dizzying pace of technological advances.

Although it could be a decade before hypersonic weapons are ready for use, U.S. military planners and contractors salivate over the prospect they could provide a game-changing military advantage. But other nations, including other nuclear-armed powers, are developing similar capabilities as they seek to counter more than 25 years of U.S. post-Cold War military dominance.

Although it could be a decade before hypersonic weapons are ready for use, U.S. military planners and contractors salivate over the prospect they could provide a game-changing military advantage. But other nations, including other nuclear-armed powers, are developing similar capabilities as they seek to counter more than 25 years of U.S. post-Cold War military dominance.

The pursuit of this emerging technology is drawing warnings that it could lead to new escalation dangers in a conflict, including to the nuclear level, and that interested countries are not giving enough attention to the potential for a dangerous arms race and increased risks of instability. To further complicate matters, hypersonic missiles could provide a new means of delivery for nuclear warheads.

Unique capabilities make hypersonic weapons more difficult to defend against than legacy missiles and “further compress the timelines for a response by a nation under attack,” according to a major 2017 Rand Corp. report, “Hypersonic Missile Nonproliferation: Hindering the Spread of a New Class of Weapons.” There is “probably less than a decade available to hinder the proliferation process,” the report says.

Hypersonic missiles can travel at approximately 5,000 to 25,000 kilometers per hour, or 1 to 5 miles per second. They can change their trajectories during flight and fly at odd altitudes. The flight altitude and maneuverability result in less warning time than in the case of higher-flying ballistic missiles. Any effort to thwart such systems would be “challenging to the best missile defenses now envisioned,” according to the Rand report.

Two types of hypersonic missiles are currently under development. A hypersonic boost-glide vehicle is fired by rockets into space and then released to fly to its target along the upper atmosphere. Unlike ballistic missiles, a boost-glide vehicle flies at a lower altitude and can change its intended target and trajectory repeatedly during its flight. The second type, a hypersonic cruise missile, is powered through its entire flight by advanced rockets or high-speed jet engines. It is a faster version of existing cruise missiles.

The United States, China, and Russia are leading the emerging race in the development of hypersonic weapons, but they are not the only countries engaged in research and development on the technology or that might seek to acquire it.

In 2003, Washington began formally pursuing options to quickly strike high-value targets with conventional weapons anywhere on the globe at the outset of or during a conflict. The effort has become known as conventional prompt strike.

Supporters inside and outside of government put forward several rationales for this mission, including countering increasingly sophisticated air and missile defense systems, destroying rogue-state nuclear forces, and targeting terrorists.

The United States conducted its first successful flight test of a boost-glide weapon in 2011, when the Army’s Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW) flew for 2,400 miles from Hawaii to the Kwajalein Atoll in the Pacific Ocean.

On Oct. 30, 2017, the Navy conducted a $160 million test in the Pacific of a modified version of the AHW that could be deployed atop missiles on Virginia- or Ohio-class submarines. Additional program flight tests are planned in 2020 and 2022.

The Defense Department has spent a total of $1.2 billion on its prompt-strike program. It requested $202 million for the program in its fiscal year 2018 budget request published in May, including $197 million for the AHW.

China and Russia have not sat idle. The two countries appear to be developing the technology in part to penetrate U.S. missile defenses.

Since 2014, China has conducted at least seven tests of a hypersonic glide vehicle, which U.S defense officials call the WU-14. It is believed to have conducted one or two tests of a hypersonic cruise missile.

In addition, The Diplomat reported in December that China in November conducted two flight tests of a new, medium-range glide vehicle, dubbed the DF-17, that is intended for operational deployment as early as 2020.

Russia has repeatedly expressed concern that U.S. prompt-strike efforts could threaten the survivability of Moscow’s nuclear deterrent. Russia is engaged in its own work on hypersonic missiles, notably the Tsirkon, or Zircon, hypersonic cruise missile.

It is uncertain whether China and Russia are developing hypersonic weapons to deliver nuclear or conventional weapons.

After the United States, China, and Russia, the two governments that have made the most progress on hypersonic technology are France and India. Both are pursuing hypersonic cruise missile options. Australia, Japan, and the European Union are also pursuing research and development programs in hypersonic technology.

The most highlighted risk to strategic stability posed by hypersonic or other prompt-strike weapons armed with conventional warheads is that they could be mistaken for nuclear weapons. This could trigger a nuclear-armed country, targeted by such a conventional attack, to launch its nuclear weapons in response.

But there are arguably more significant stability concerns. For example, the deployment by nuclear-armed states of conventional hypersonic missiles could pose a threat to the survivability of their nuclear forces and potentially reduce the available response time. By increasing fears of a disarming attack, a threatened state could take steps that would increase crisis instability, such as increasing the readiness of its nuclear forces or adopting a policy of pre-emption.

Chinese and Russian officials and analysts have expressed concerns about this type of scenario.

Further, the advent of hypersonic weapons could increase the growing risks of inadvertent escalation related to the “entanglement” of non-nuclear weapons with nuclear weapons and their supporting capabilities, such as command-and-control functions. Given that the actual targets of a hypersonic missile attack might not be apparent until the last minutes of flight, a state could misattribute an attack aimed at its conventional forces as an attack against its nuclear forces nearby.

The proliferation of hypersonic weapons beyond the United States, China, and Russia could exacerbate stability concerns. The Rand study noted that the spread of the weapons “could result in lesser powers setting their strategic forces on hair-trigger states of readiness and more credibly being able to threaten attacks on major powers.”

Experts concerned about the risks to stability have proposed ideas to mitigate them. For instance, as a unilateral step, countries developing these missiles could make escalation risks a key factor in the decision about whether to acquire and deploy the weapons.

James Acton, co-director of the nuclear policy program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told Arms Control Today in a Dec. 21 interview that the U.S. hypersonic program is technology driven and the Pentagon has not adequately explained why it needs such a capability or assessed the benefits, risks, and costs.

Cooperative steps also could be pursued, although progress does not appear likely in the near term given tensions among the major powers. As one idea, the United States could initiate separate dialogues with China and Russia on stability and escalation concerns and on developing confidence-building measures. Such measures could include data exchanges on hypersonic deployment and acquisition plans.

In addition, the three countries could agree to multilateral export controls to restrain the proliferation of hypersonic technology.

More far-reaching measures could also be contemplated. In a report published last November by the Carnegie Endowment, Russian scholars Alexey Arbatov, Vladimir Dvorkin, and Petr Topychkanov urged the inclusion of intercontinental boost-glide systems under the central limits of a successor to the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START).

Some analysts have called for enacting a moratorium on hypersonic testing and eventually establishing a test ban treaty. Mark Gubrud, a physicist and adjunct assistant professor in the peace, war, and defense curriculum at the University of North Carolina, has written that a test ban would be “a simple, risk-free, and highly verifiable way” to avoid “a new round of an old arms race.”

But Acton told Arms Control Today he is skeptical about the feasibility of a test ban. He noted that there is no clear dividing line between boost-glide vehicles and terminally guided ballistic missiles, such as the Chinese DF-21, which maneuvers to its target after re-entering the atmosphere. “If all maneuvering re-entry vehicles are banned,” Acton said, “China will never sign up.”