Trump Seeks More Pressure on North Korea

December 2017

By Kelsey Davenport

U.S. President Donald Trump during a trip to Asia publicly urged North Korean leader Kim Jong Un to “come to the table” to negotiate over the country’s nuclear program, as he pressed regional leaders to increase economic pressure on the Pyongyang regime.

Although his rhetoric toward North Korea during the trip was less aggressive than recent statements and tweets, Trump still did not lay out a strategy for engagement and continued to send mixed signals about what the United States wants to see from North Korea before engaging in talks. Trump’s trip included stops in Japan, South Korea, and China, with the North Korea challenge a key agenda item in his talks.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said at a Nov. 6 press conference with Trump that Japan would adopt additional sanctions measures on North Korea. “Now is not the time for dialogue but for applying the maximum level of pressure on North Korea,” he said.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said at a Nov. 6 press conference with Trump that Japan would adopt additional sanctions measures on North Korea. “Now is not the time for dialogue but for applying the maximum level of pressure on North Korea,” he said.

In South Korea, President Moon Jae-in said on Nov. 7 that he and Trump affirmed their “current strategy, which is to maximize pressure and sanctions on North Korea until it gives up nuclear weapons” and comes to the table for dialogue “on its own.” He said that the goals must be to freeze and “ultimately dismantle” North Korea’s nuclear weapons and that the timing is not right to discuss replacing the 1953 armistice with a “permanent peace on the Korean peninsula.”

Despite having affirmed a shared strategy toward addressing North Korea’s nuclear program, Moon’s comments are at odds with statements by U.S. officials, who have discounted the value of purusing a freeze deal with North Korea. Trump said at the same briefing that all nations must “cease trade and business entirely with North Korea” and fully implement UN Security Council resolutions.

When pressed on his diplomatic strategy, Trump said in Seoul, “[W]e’re making a lot of progress,” but provided no details, stating that he does not like to talk about whether he sees a diplomatic outcome to avert threatened U.S. military action.

Still, after earlier threats to rain down “fire and fury” on North Korea, Trump’s comments appeared aimed at easing regional alarm that he was careening toward a potentially nuclear conflict on the Korean peninsula that could extend to Japan and beyond, given the range of North Korea’s nuclear-capable ballistic missiles. North Korea also has chemical weapons and is thought to have biological weapons capabilities.

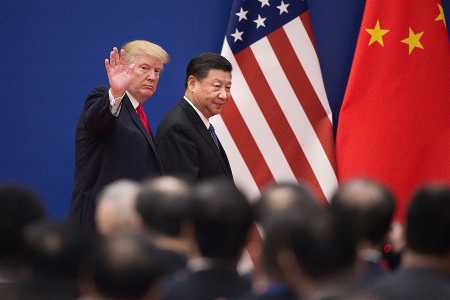

No additional detail was provided during Trump’s stop in China, which the U.S. administration sees as the country most able to influence North Korea’s leadership. In a Nov. 9 press statement, Chinese President Xi Jinping said the United States and China are committed to “working toward a solution through dialogue and negotiation” to achieve denuclearization of the Korean peninsula.

Trump said he and Xi would not “replicate failed approaches of the past” that unsuccessfully sought denuclearization. Even so, Trump’s remarks during his Asia trip demonstrate that his policy remains similar to that of U.S. President Barack Obama, namely to ratchet up pressure and insist that North Korea take steps toward denuclearization as a precondition for beginning negotiations. But although Obama declared a policy of “strategic patience” even as North Korea advanced production of nuclear warheads and ballistic missiles, Trump has said that the clock is running out to stop North Korea before it produces reliable, nuclear-armed ballistic missiles able to strike major U.S. cities.

Trump has progressively increased pressure on North Korea through unilateral U.S. actions, most recently by designating North Korea as a state sponsor of terrorism on Nov. 20, and by supporting more aggressive UN Security Council measures. Along with seeking to curtail North Korea’s key trade relations, the United States is pressing countries such as Kuwait and Qatar to stop using North Korean construction laborers, whose employment provides a major source of foreign currency for the isolated North Korean government.

Unlike during his stops in Seoul and Tokyo, Trump in Beijing did not single out China to better enforce UN Security Council sanctions, but said in Nov. 9 remarks with Xi that Washington and Beijing were in agreement to “increase economic pressure until North Korea abandons its reckless and dangerous path.”

Trump and Xi did not take questions from the press. U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson told reporters that there is “no disagreement” between the leaders on the goal of negotiations with North Korea but the two countries favor different tactics.

China supports a resumption of the so-called six-party talks, which took place from 2003 to 2009, and has proposed that North Korea freeze nuclear and missile testing in return for a suspension of U.S.-South Korean military exercises.

Shortly after Trump’s visit, China announced Nov. 15 that it was sending a high-level envoy to Pyongyang, likely to push for a resumption of talks. The four-day visit was the first to North Korea's capital by a high-level Chinese envoy in two years.

According to the official announcement from Beijing, Song Tao, the head of government’s external affairs department, would inform North Korea about the outcome of the Communist Party Congress, which took place in October and reappointed Xi Jinping to a second term as president. Experts interpreted the wording of the announcement to mean that Song likely also would urge North Korea to engage in negotiations over its nuclear program.

Trump also focused on the U.S. security alliances with South Korea and Japan during visits and said that Washington stands ready to “defend itself and its allies using the full range of our unmatched military capabilities.”

Moon said on Nov. 7 that he and Trump agreed to expand the rotational deployment of U.S. strategic assets in and around the Korean peninsula and to discuss South Korea’s acquisition and development of military reconnaissance assets.

Moon also confirmed that Seoul and Washington reached a final agreement to eliminate the payload limit on South Korean ballistic missiles. Trump had already agreed in principle to lift the limit in September after North Korea’s sixth nuclear test. (See ACT, October 2017.)

China, South Korea Drop THAAD Dispute China and South Korea set aside what had been a disruptive dispute since South Korea deployed a U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) battery earlier this year. The Chinese and South Korean foreign ministries released a joint statement Oct. 31 on restoring normal diplomatic relations. The two countries said they would resume all cooperation and trade “expeditiously” and cooperate on reaching a peaceful resolution of the North Korean nuclear crisis. China had encouraged an informal boycott against South Korean companies this year, pushing South Korean President Moon Jae-in closer to the United States. It is unclear what prompted China’s sudden shift because South Korea offered no significant concessions on the THAAD dispute or change in policy. Chinese President Xi Jinping may have decided that economic sanctions were failing to erode the U.S.-South Korean alliance and may have seen an opportunity to exploit the growing discomfort among many South Koreans with what they perceive as U.S. President Donald Trump’s aggressive approach toward North Korea. China maintains its opposition to the THAAD deployment, but acknowledged South Korea’s reassurances that the missile defense system is not aimed at China and that it would not deploy more THAAD batteries, participate in a U.S.-led strategic missile defense system, or form a NATO-like U.S.-Japanese-South Korean military alliance. China’s economic actions hurt elements of South Korea’s economy, particularly the tourism sector. The number of visiting Chinese tourists fell by half in the first nine months of this year, which cost the economy $6.5 billion in lost revenue based on the average spending of Chinese visitors in 2016, according to data from the Korea Tourism Organization cited by Reuters. China also restricted imports of South Korean cosmetics, barred performances by K-pop musical groups, and ramped up criticism in official media of the South Korean government. Moon and Xi met on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Danang, Vietnam, on Nov. 11, where they reiterated the agreement to quickly normalize bilateral relations and agreed to hold further talks on managing the North Korean crisis, according to South Korean presidential spokesman Yoon Young-chan.—MACLYN SENEAR |