“For 50 years, the Arms Control Association has educated citizens around the world to help create broad support for U.S.-led arms control and nonproliferation achievements.”

Brexit Has Nuclear Consequences for UK

July/August 2017

By Kelsey Davenport

The United Kingdom’s decision to pull out of a treaty establishing nuclear cooperation in Europe, as part of its overall withdrawal from the European Union known as Brexit, will have significant implications for UK nuclear activities. If London does not take steps in the next few years to fill the void, the UK’s nuclear trade and access to research projects could suffer.

The UK is a party to the 1957 treaty that established the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) to coordinate civil nuclear energy research and create a market for developing nuclear power. Euratom also plays a role in implementing safeguards, which provide assurances that nuclear activities are for peaceful purposes. The UK joined Euratom in 1973, and membership now includes all EU states.

Following Brexit, the UK will need to reach new bilateral cooperation agreements with the United States and other countries to continue civil nuclear trade. It will also need to revise its nuclear safeguards arrangements and determine how to engage with Euratom on projects, such as fusion research, in which the UK is heavily invested.

Following Brexit, the UK will need to reach new bilateral cooperation agreements with the United States and other countries to continue civil nuclear trade. It will also need to revise its nuclear safeguards arrangements and determine how to engage with Euratom on projects, such as fusion research, in which the UK is heavily invested.

It was not a foregone conclusion that Brexit would include withdrawal from Euratom. Although legal experts differ on whether the UK had to withdraw from Euratom, a governmental white paper in February noted that Euratom uses the same institutions as the EU and, under UK law, references to the EU include Euratom.

In March, UK Prime Minister Theresa May’s EU withdrawal notification to the European Council included leaving Euratom. Previously, Jesse Norman, the then-UK minister for energy and industry, called withdrawal from Euratom a “regrettable necessity” in remarks Feb. 27 to the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology.

New Safeguards Agreement

One critical area where Euratom plays a role is in implementing nuclear safeguards. Euratom safeguards predate the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and its requirement for non-nuclear-weapon states to implement safeguards arrangements with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to pursue peaceful nuclear activities. When the UK joined Euratom, its civil nuclear activities were subject to Euratom safeguards.

The UK, as a recognized NPT nuclear-weapon state, does not have the same NPT obligations as non-nuclear-weapon states, but it reached a voluntary safeguards agreement with the IAEA and Euratom for its civil program in 1978 and an additional protocol to strengthen its IAEA safeguards in 2004.

Implementation of Euratom safeguards is a component of the IAEA’s implementation of safeguards for Euratom member states. For instance, Euratom provides the IAEA with information on nuclear material accounting and transportation. The IAEA also conducts some safeguards inspections jointly with Euratom and verifies Euratom safeguards activities through observation.

Withdrawal from Euratom will require changes in the UK approach to safeguards and in domestic provisions for providing IAEA information and access. Some experts contend that the UK will need to renegotiate its voluntary access safeguards agreement and additional protocol with the IAEA, given that the Euratom measures are part of the UK arrangements with the agency.

Dame Sue Ion, chair of the UK Nuclear Innovation and Research Advisory Board, told the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology on March 7 that the UK will need to “evolve other arrangements” between the UK regulator and the IAEA. She said that London will need new arrangements that “pretty much mirror” Euratom.

In a June 6 interview, a UK official speaking on condition of anonymity said it is an “urgent priority” to put in place a “solid safeguards framework,” given that nuclear cooperation agreements take safeguards into account. Ensuring effective safeguards post-Euratom, he said, will be critical to ensuring continuity in cooperative research and trade activities. Although high UK standards could still be relied on to prevent diversion, London wants to continue to lead and set an example for good safeguards practices, he said.

In a June 21 speech on the government’s intentions for the next parliament, Queen Elizabeth II mentioned a new bill that would create domestic nuclear regulations and safeguards to fill the void left by withdrawal from Euratom. Tom Greatrex, chief executive of the UK Nuclear Industry Association (NIA), said on June 21 that the bill is a necessary step for the UK to take on safeguards responsibilities, but said it does not get close to “resolving the issues they have created” by leaving Euratom.

Nuclear Research and Trade

Euratom also coordinates cooperative research in civil nuclear projects, and several scientists told ACT they are concerned about retaining access to research opportunities, facilities, and projects.

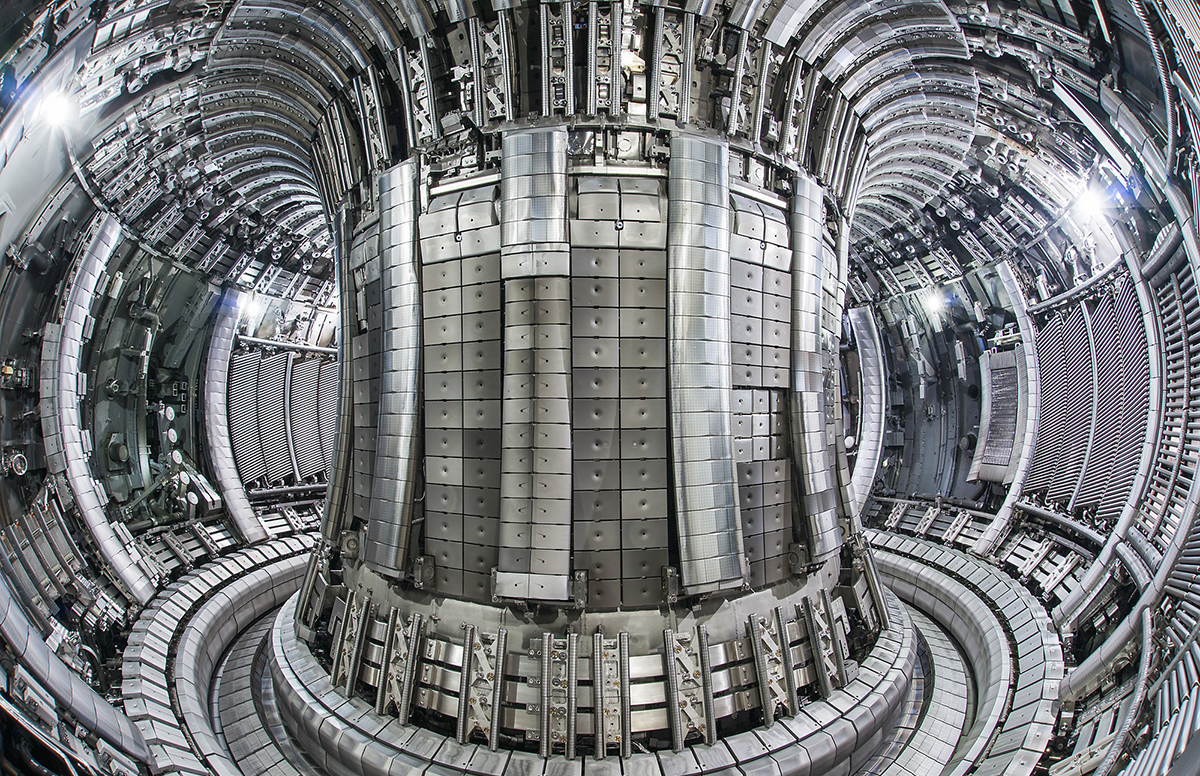

The UK is heavily invested in cooperative work to develop nuclear fusion-reactor technologies. Existing nuclear reactors use fission, or the splitting of atoms, to produce energy, whereas a fusion reactor would join atoms together to produce energy.

The UK participates through Euratom in the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), a megaproject under construction in France to demonstrate the feasibility of fusion reactors. The UK’s Culham Centre for Fusion Energy currently houses the Joint European Torus (JET) project, which is funded by the EU to examine the potential for fusion power.

The Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee report said that exclusion from programs such as JET and ITER could “disadvantage national nuclear research” and called for “special consideration” for funding arrangements that would allow continued access to these projects.

In addition to coordinating and facilitating research, Euratom also serves as the partner for U.S. civil nuclear cooperation with Europe, including the UK. In 1958 the United States and Euratom concluded the Euratom Cooperation Act, which serves as the agreement required by the 1954 U.S. Atomic Energy Act to conduct nuclear trade. Once the UK withdraws from Euratom, it will not be covered by that agreement.

In a June 8 interview, a second UK official expressed confidence that the UK would be able to negotiate with the United States a bilateral nuclear cooperation pact, often referenced as a 123 agreement, but said there could be “costly disruptions” to nuclear commerce and research if there is no substitute agreement by March 2019, the effective date for Brexit. A bilateral text is already being drafted, although details need to be worked out before the U.S. review process can begin, he said.

Other countries conducting nuclear trade with the UK via Euratom, such as Canada and Japan, also likely will be affected by London’s withdrawal.

The impact is not limited to trade. It could have implications for decommissioning nuclear facilities and nuclear waste disposal. The UK currently relies on facilities outside of the country for some of these activities, which would require new arrangements.

Moving Forward

Lord John Hutton, NIA chairman, told the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology on March 7 that the UK needs to avoid a “cliff edge” and recommended seeking associate partner status in Euratom. Taking this step, however, would not resolve all of the issues. Switzerland, for instance, is an associate partner, entitling the country to participation in some research projects, but it is not part of the Euratom safeguards agreement.

Another option proposed by Parliament’s Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy Committee on May 2 is to “seek a transitional agreement to retain our existing arrangements until new arrangement can be put in place.” The committee noted that the transition time may need to be longer than the three-year period recommended by the European Parliament as the limit for transitional arrangements between the EU and UK. The committee also noted that a delay would give the nuclear industry time to navigate the transition and “minimize any disruptions to trade and threats to power supplies.”

Euratom and other groups seem to support a longer transitional arrangement.

Foratom, the trade association for nuclear energy in Europe, said in an April 3 statement that these arrangements should apply in case the initial transition period is “not sufficient” to prevent any disruption in projects, research, and supply of nuclear fuels.—KELSEY DAVENPORT