“For 50 years, the Arms Control Association has educated citizens around the world to help create broad support for U.S.-led arms control and nonproliferation achievements.”

Sarin Attack Prompts U.S. Strikes

May 2017

By Kelsey Davenport

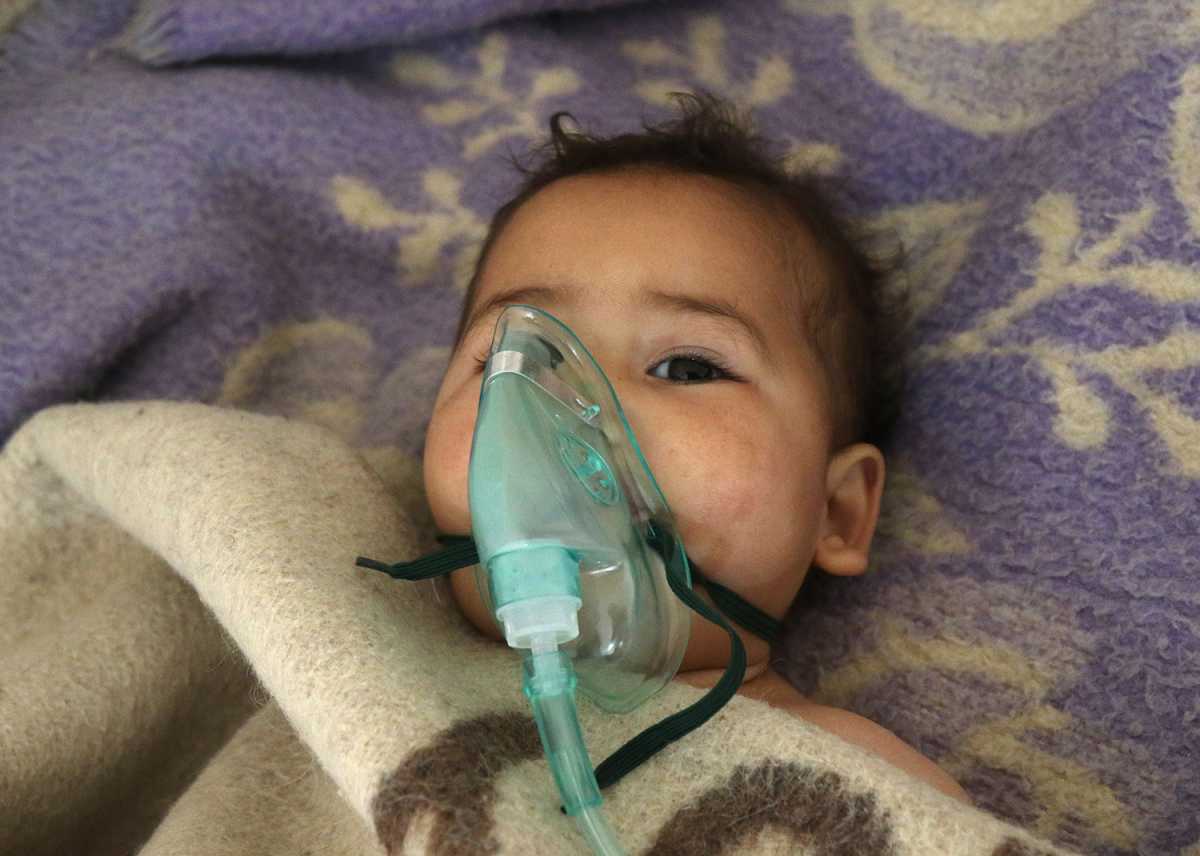

Syrian government forces conducted a deadly attack on an opposition-held area using chemical weapons, prompting the United States to launch a retaliatory strike against a Syrian air base.

The chemical weapons attack, which used the nerve agent sarin, and the subsequent U.S. missile strike generated mixed responses in the UN Security Council, which remains deadlocked over further action responding to the Assad regime’s repeated use of toxic chemicals.

In an April 7 statement announcing the cruise missile strike, U.S. President Donald Trump said that the target, the Shayrat air base, had been used by Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad three days earlier as the staging ground for the chemical weapons attack on Khan Shaykhun in Idlib province. The April 4 attack reportedly resulted in 50 to 100 civilian casualties.

The Syrian government denied responsibly for using chemical weapons and claimed that the reports were fabricated, but Trump said that there “can be no dispute that Syria used banned chemical weapons” to attack Khan Shaykhun. It was “vital to the national security interest of the United States to prevent and deter” the spread and use of chemical weapons, he said.

According to a declassified U.S. report released April 11 by the White House, victims of the chemical weapons attack showed signs of exposure to sarin, a toxic agent outlawed by the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). Physiological samples detected sarin as well, according to the report.

The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which oversees the CWC, said on April 13 that its designated laboratories were analyzing samples collected from the site and inspectors would continue to investigate the incident. On April 19, OPCW Director-General Ahmet Üzümcü said that evidence, including analysis of autopsy samples from three victims, showed “incontrovertible” evidence of exposure to “sarin or a sarin-like substance.”

The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which oversees the CWC, said on April 13 that its designated laboratories were analyzing samples collected from the site and inspectors would continue to investigate the incident. On April 19, OPCW Director-General Ahmet Üzümcü said that evidence, including analysis of autopsy samples from three victims, showed “incontrovertible” evidence of exposure to “sarin or a sarin-like substance.”

Russia explained the presence of sarin by arguing that Syrian aircraft struck a rebel-held chemical weapons facility in Khan Shaykhun, a scenario that seemed to contradict Syrian military statements that no aircraft conducted strikes in that region. Russia’s response “follows a familiar pattern” of issuing “multiple conflicting accounts in order to create confusion and sow doubt within the international community,” according to the declassified U.S. intelligence report.

The intelligence report also noted that Syria used sarin in an August 2013 attack on a Damascus suburb. (See ACT, September 2013.) The subsequent threat of U.S. military action by President Barack Obama prompted an agreement, brokered by the United States and Russia, under which Syria agreed to ship out all of its chemical weapons, destroy production facilities, and ratify the CWC. (See ACT, November 2013.) Although Syria claims it fulfilled its obligations, the OPCW is investigating whether Syria failed to declare all of its chemical weapons stockpiles and facilities as required.

Rebecca Hersman, director of the Project on Nuclear Issues at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Arms Control Today on April 17 that “gathering and preserving critical evidence and victim accounts remains essential, as does a detailed and intrusive reinvestigation of the Syrian declaration regarding its chemical weapons program.”

Additionally, the UN Security Council, in conjunction with the OPCW, is investigating other alleged instances of chemical weapons use in Syria after Assad acceded to the convention. The reports issued by the UN-OPCW Joint Investigative Mechanism in 2016 attributed three attacks using chlorine to the Syrian government and one attack using sulfur mustard to the Islamic State group. (See ACT, November 2016.) Additional cases are still being investigated.

Hersman, who served as U.S. deputy assistant secretary of defense for countering weapons of mass destruction from 2009 to 2015, said there is “no legal distinction” between dropping barrel bombs with chlorine or sarin-filled munitions, as both are prohibited by the CWC. The accord does not prohibit the possession of chlorine, given its industrial uses, but it does prohibit the chemical’s use as a weapon.

Investigating and holding accountable entities is “no less essential for attacks involving chlorine or other toxic, asphyxiating chemicals than for sarin,” said Hersman. The “parsing of these attacks into more [acceptable] or less acceptable based on their chemical properties or emotional perceptions about types of agents has the potential to fundamentally unravel the entire Chemical Weapons Convention as well as the basis of our definition of these acts as war crimes under the International Criminal Court [ICC],” she said.

Investigating and holding accountable entities is “no less essential for attacks involving chlorine or other toxic, asphyxiating chemicals than for sarin,” said Hersman. The “parsing of these attacks into more [acceptable] or less acceptable based on their chemical properties or emotional perceptions about types of agents has the potential to fundamentally unravel the entire Chemical Weapons Convention as well as the basis of our definition of these acts as war crimes under the International Criminal Court [ICC],” she said.

The Rome Statute, which established the ICC, includes in its definition of a war crime using gas or similar substances in a way that “causes death or serious damage to health in the ordinary course of events, through its asphyxiating or toxic properties.”

Syria is not a state-party to the ICC, but the UN Security Council could refer Syria for investigation by the court. Russia would likely veto such a resolution, but there is validity in raising a referral to help build a case for future accountability, said Hersman.

Security Council Response

The Security Council met several times in April to discuss the chemical weapons attack and subsequent U.S. strike. The meetings culminated April 12 with Russia vetoing a resolution by France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The resolution condemned the April 4 chemical weapons attack, emphasized the need for Syria to provide full access for investigators, and expressed determination to hold perpetrators accountable.

UK Ambassador Matthew Rycroft called the resolution the “necessary minimum response to the incident” and said it is “indefensible that Russia has chosen to protect the perpetrators of these attacks” rather than work with the international community. “We will hold the regime to account” for these “heinous chemical attacks,” he said, although the council has been hamstrung for years by Russia’s protection of the Assad regime, its main Middle Eastern ally.

Russian envoy to the United Nations Vladimir Safronkov said his country vetoed the resolution because blame for the chemical weapons attack was assigned to the Syrian government before an investigation was conducted. He also questioned the impartiality of OPCW investigative methods and called for wider geographic representation in the staffing for future investigations. Bolivia joined Russia in voting against the resolution, while China, Ethiopia, and Kazakhstan abstained.

Despite the failure of the resolution, the Security Council did extend the mandate of the UN-OPCW Joint Investigative Mechanism for an additional year. Hersman said that the United States has options, such as working with other countries on sanctions, to pressure Assad for diplomatic resolution of the conflict. “The lasting effects of airstrikes on air fields or other targets will be fleeting if the United States cannot use power and influence” to drive the parties to negotiate, she said.

Despite the failure of the resolution, the Security Council did extend the mandate of the UN-OPCW Joint Investigative Mechanism for an additional year. Hersman said that the United States has options, such as working with other countries on sanctions, to pressure Assad for diplomatic resolution of the conflict. “The lasting effects of airstrikes on air fields or other targets will be fleeting if the United States cannot use power and influence” to drive the parties to negotiate, she said.

Russia denounced the U.S. military action in which 59 Tomahawk cruise missiles hit targets such as aircraft and facilities. Safronkov told the Security Council on April 7 that Moscow strongly condemned the “illegitimate actions” taken by the United States and said the strike could have consequences for regional and international stability.

Trump’s decision to respond with military force generally drew approval from U.S. lawmakers, but Sens. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and Tim Kaine (D-Va.) criticized the president for not obtaining authorization from Congress. The action was a reversal by Trump, who at the time of the 2013 chemical attack tweeted that Obama should not attack Syria and that striking Syria without congressional approval would be a “big mistake.”