Price Tag Rising for Planned ICBMs

October 2016

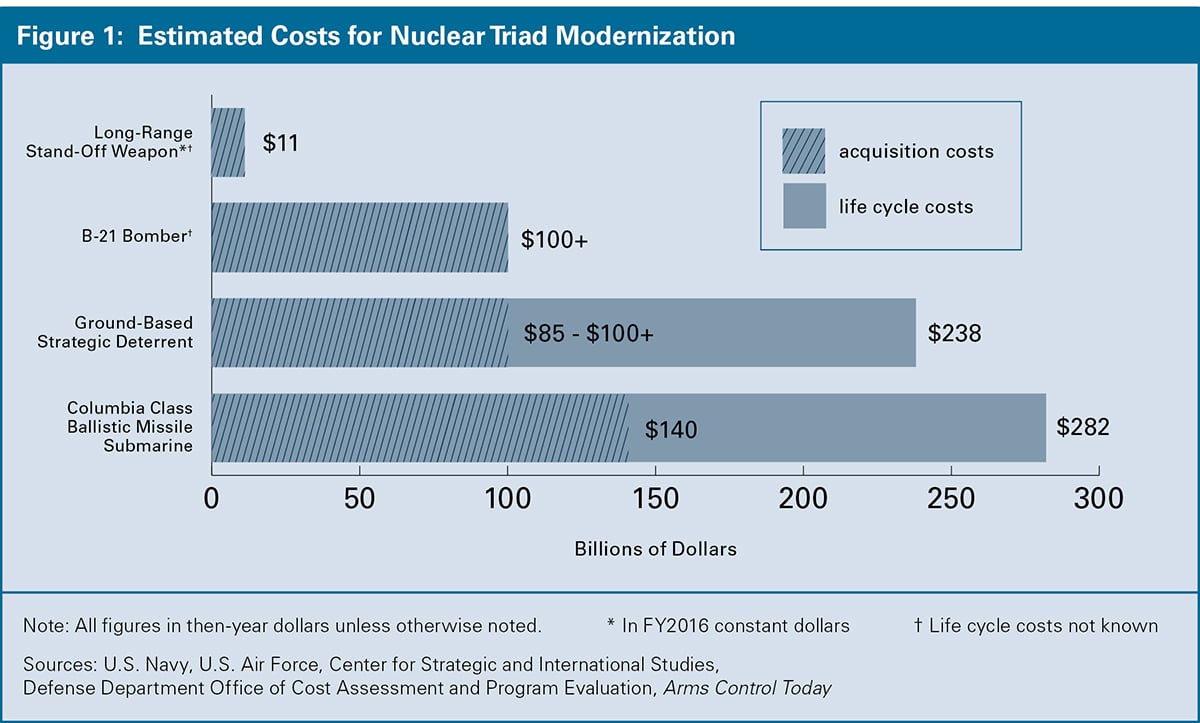

The projected $85 billion cost to design and build a replacement for the Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) system, the figure set by the Defense Department’s top acquisition official in advancing the program, is at the low end of an independent Pentagon estimate that found the price tag could exceed $100 billion, an informed source told Arms Control Today.

The Air Force last year published an initial cost estimate of $62.3 billion for the replacement program. (See ACT, July/August 2015.)

The estimate of $85 billion to more than $100 billion was prepared by the Pentagon’s Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) in support of the program’s milestone A decision, a key early benchmark in the acquisition process for the weapons system. Frank Kendall, undersecretary of defense for acquisition, technology, and logistics, approved the milestone A decision on Aug. 23, the Air Force announced in a Sept. 1 press release.

CAPE provides the Defense Department with detailed analysis of the costs of major acquisition programs. The estimate, in then-year dollars, includes inflationary increases expected over the life of the program.

The approved $85 billion program cost baseline is contained in a document written by Kendall known as an acquisition decision memorandum and includes the cost to purchase 666 new missiles and rebuild the existing missile infrastructure, the source said. The higher $100 billion-plus CAPE figure is not included in the memo, the source added.

The projected cost to operate and sustain the weapons system over its expected 50-year service life is roughly $150 billion, putting the total cost of the GBSD program at $238 billion, according to the source.

Bloomberg News was the first to report on the $85 billion estimate set by Kendall.

Cost Estimates Uncertain

Kendall’s approval of the milestone A decision was reportedly delayed due to the large gap between the cost estimate prepared by the Air Force and the more recent independent estimate prepared by CAPE. (See ACT, September 2016.)

According to the Bloomberg report, Kendall wrote in the acquisition memo that “there is significant uncertainty about program costs” because “the historical data is limited and there has been a long gap since the last” time the U.S. government built an ICBM.

In remarks at an event on Capitol Hill on Sept. 22, Jamie Morin, the director of CAPE, said that there were “nontrivial” differences in how the CAPE and Air Force cost estimates were built, including contrasting inputs on the missile portion of the replacement program and assessments of the program’s overall “complexity.”

According to Morin, CAPE based its cost calculations on historical data that could be culled from previous ICBM procurement efforts, such as the Minuteman and Peacekeeper programs, as well as data from the Missile Defense Agency and the Navy’s Trident missile program.

Like Kendall, Morin emphasized the uncertainty of the cost estimate at this early stage of the acquisition process and noted that it is rare for CAPE to publish low- and high-end estimates for a major program.

Questions Raised

The projected cost of the GBSD program could add to worries about the affordability challenges posed by U.S. nuclear weapons spending plans. (See ACT, May 2016.)

In remarks June 6 at the Arms Control Association’s annual meeting in Washington, Benjamin Rhodes, assistant to the president and deputy national security adviser for strategic communications, said President Barack Obama would continue to evaluate plans that envision ramping up spending in the coming years to maintain and modernize U.S. nuclear weapons and would decide whether to “leave the next administration” with recommendations on how to “move forward.” (See ACT, June 2016.)

“Our administration has already made plain our concerns about how the modernization budget will force difficult trade-offs in the coming decades,” Rhodes added.

Rhodes did not specify a timeline for when the president would make a decision on whether to adjust the modernization plans and, if so, when he would announce it.

Meanwhile, some analysts are questioning whether the GBSD program is the most cost-effective way to maintain the ICBM leg of the triad.

Prior to the cost analysis conducted by CAPE, the Air Force had been arguing that the price to build a new missile system would be roughly the same as the cost to sustain the Minuteman III over the next 50 years and would not provide desired capability upgrades. (See ACT, April 2016.)

But a 2014 report by the RAND Corp. on the future of the ICBM force found that “any new ICBM alternative will very likely cost almost two times—and perhaps even three times—more than incremental modernization of the current Minuteman III system.”

The report said continuing to maintain the Minuteman III through life-extension programs and “gradual upgrades is a relatively inexpensive way to retain current ICBM capabilities.”

In a Sept. 22 interview with Arms Control Today, Todd Harrison, director of defense budget analysis and a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said he did not see a technical reason why the life of the Minuteman III could not be extended for a period of time beyond 2030 if the missile’s solid fuel propellant was replaced and the Pentagon forwent capability upgrades.

Another life extension of the Minuteman III would allow the Air Force to defer a decision on whether to build a replacement system, thereby easing some of the pressure current nuclear and conventional weapons spending plans will put on the defense budget over the next 15 years, Harrison added.